|

→ November 2006 Contents → Column

|

TV News in a Postmodern World:

The Transparency Marketplace November 2006

|

|

|

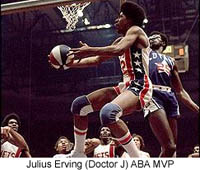

When the flamboyant American Basketball Association (ABA) merged So it is with media companies in the face of the Media 2.0 disruption. So-called mainstream media will ultimately merge with the disruption and adopt its new rules or be swallowed up by it entirely. And high on the list of new rules is an entirely different approach to advertising, one that relies on empirical proof of performance instead of sample-based methodologies. This is what smart ad executives mean when they refer to "transparency" — precision in a world formerly dominated by blue smoke and mirrors. A mainstream media executive recently said to me, "Terry, it's all the same game, whether there actually is mass or a perception of mass, it's still about offering those people to advertisers." Well, it is, but it isn't. Among other things, what's different is that the disruption relies on precise measurement of those people, whereas the business model of the mainstream has always relied on scientific estimates. This is not a semantic argument, nor is the eventual embracing of the measurement disruption optional. The other element of transparent measurement is direct proof-of-performance through clicking on links. This is the foundation of Google's strength — delivering predisposed customers to businesses online. It's not about fancy, award-winning 30-second commercials; it's about the measurable ability to put customers in the showroom, and it's raising eyebrows everywhere. It's cheap, efficient and gaining reliability for the people who pay, and that spells trouble for those who count on the continued big budgets of reach-frequency estimates. In dealing with television station groups, I often hear "None of this stuff matters, Terry, because we live in the world of Nielsen. If it doesn't have a Nielsen number, we don't care about it." But it is Nielsen's world that is most threatened by the transparency paradigm, and this is something few people wish to honestly discuss. Billions of dollars are at stake through traditional sample-based methodologies, and a collapse here could have wide-ranging implications for the whole economy. When Nielsen announced earlier this year that it would begin providing television ratings for commercials this fall, the whole industry trembled. And now it appears a delay is likely. Joe Mandese, editor of MediaDailyNews told readers of a hasty gathering of "all sides" in the commercial ratings concept in an effort to halt or slow down the Nielsen plan. Alan Wurtzel, president of research and media development at NBC (and one of researching's most amazing spin doctors) told Mandese, "I don't think there's anyone out there who thinks that Nielsen has a full grip on this. We need to find a forum in which the industry can get together and start to deal with some of these details." One of the chief problems surrounding the new ratings is that the commercial ratings are processed by using a relatively shaky system for identifying when the commercial minutes actually air. That system, Nielsen's Monitor-Plus service, was designed as a competitive advertising monitory system, which apparently does not have the same level of detail or rigor as the systems Nielsen uses to compile and process TV ratings. But there are others — especially leading edge thinkers in the advertising world — that think even Nielsen's process of TV ratings cannot possibly provide accurate measurements in today's fragmented marketplace. One of them is Tim Hanlon, senior vice president of Ventures for Denuo, the media futures consulting practice of Publicis Groupe. It's very difficult for me to believe that a sample-based methodology over 10,000 homes as a representation of the entire country can accurately measure what's really happening over hundreds of media possibilities. We have such a myriad of choices including hundreds of hours of video-on-demand, and the variability of each individual's habits just seems infinite. So a 10,000-person sample, people-metered or not, is still sample-based methodology. What Hanlon and others see coming from the advertising side of the relationship is a question that must be answered sooner or later. Even in its most primitive forms, broadband video provides far more data than advertisers ever got before, and the question is "why can't we do this with television?" The question, says Hanlon, is rhetorical in nature, but it must be answered. "These people are driving the intellectual curiosity," he said, "and there's an expectation that all media needs to be similarly proven." My belief is that television becomes a series of data points for people like us to measure and discern instead of just a simple Nielsen rating for program or commercial. We need to be much more sophisticated, and our online people get that, but our television and print buyers don't, because they're still stuck with a heritage of crude data points that are accepted with a smile, a wink and a nod. Hanlon points out that advertising data is becoming more sophisticated "by the week" and that the existing system isn't transforming fast enough. The four billion dollar ad machine known as Google is creating the future, and "they didn't ask Madison Avenue for permission to do it." More evidence that the transparency provided by technology is completely disrupting the TV ad game came recently from a group of big players. Nine major television advertisers, including Wal-Mart, Microsoft and Toyota, are funding a project to create an online auction for television spots. They've hired eBay to create the application and are hoping to avoid the costly network "upfront" by using this as a way to buy advertising availabilities. $50 million has been committed to the project, and listen to what Ann Bybee, corporate manager, Lexus Advertising, Brand and Product Strategy has to say about it. "To be effective in the future our processes must embrace the advancements in technology and the benefits of our digital world." Jeff Jarvis, whose popular Buzzmachine blog offers a cutting edge view of all things media, calls it "a pipe dream for marketers and a nightmare for the networks." The creators of the new e-Media Exchange are making noises about this not being the end of TV upfront. But it is. This is the end of control by scarcity. TV time is just more advertising now, and the days of raising rates even as audience shrank are over. Now the market will set the price. Watch out, Hollywood. A third consideration in the "Nielsen is everything" paradigm is that new metrics are being developed by third-party internet companies that will provide even more data points for ad execs to consider. As television moves more consistently to TV over IP or IPTV, these metrics will play a role in ad rates, but they are invisible to most mainstream media companies today, because they have no bearing in the old circulation or ratings models. Chief among these new metrics is the ability to measure inbound links to a Website, which most consider a way to assign "influence" to a content provider, whether that's a blog or a traditional media site. Since this element is a major consideration in Google page ranking — and Google is THE source of search traffic — everyone who does media business via the web should be involved in encouraging links. Very few mainstream sites do this, however, because the operators are still living in old models of doing business, where reach is more important than links. Every mainstream media company should have on its staff an expert in search engine optimization and not rely on a third-party to help with this important element in Media 2.0. The transparency marketplace is going to get more and more active over the next five to ten years, and during this time we'll likely see combinations of measurement and impression-based data move to the forefront in the setting of advertising rates. Consumers who are interested in ads will be able to dig deeper and perhaps even make a purchase of items like CDs and DVDs. Technology is making possible — with remarkable accuracy — the ability to deliver the right message to the right audience at the right time. There will likely be wars with viewers over this, because one of the most important elements of the Media 2.0 world is that the people formerly known as consumers are in charge, and unwanted messages — which means most mass marketing ads — run the risk of producing exactly the opposite of the desired effect. Is it possible to do permission-based mass marketing? Television's old assumption that the audience provides the permission because the programming is free is just one of many that are being challenged by new media. Hanlon, who cut his teeth in the television business, has some important words of wisdom for people in the industry: If I run a TV station, and I'm at least smart enough to understand that I'm not just one linear channel, I'm exposed to great examples as to why I need more sophisticated measurement data. Nielsen doesn't measure HDTV, for example, because the number of people using it isn't big enough for their methodology. But in very high-end homes, do you mean they don't exist? HD Net doesn't exist? People watching the World Cup aren't real? In the end, if the Media 2.0 opportunities are targeted to what the advertisers want, then they will have value and great value. The quality of the targeted audiences is likely higher on line than it is in the broadcast world, but ad rates are much lower. This is the key to watch as the transparency marketplace evolves. Will it ever provide the same kinds of revenue levels to which mainstream players are accustomed through a methodical game of lay-ups and 2-point shots? That is the multi-billion dollar question.

© Terry Heaton

|

|

Back to November 2006 Contents

|

|

with the National Basketball Association in 1976, the deal brought with it more than new teams in new cities. The ABA was a running, gunning and highly entertaining form of professional basketball, so the merger brought with it the 3-point shot and returned the slam dunk to the game. In the end, the NBA still played basketball, but it did so with different rules, rules that ultimately led to its current freewheeling style.

with the National Basketball Association in 1976, the deal brought with it more than new teams in new cities. The ABA was a running, gunning and highly entertaining form of professional basketball, so the merger brought with it the 3-point shot and returned the slam dunk to the game. In the end, the NBA still played basketball, but it did so with different rules, rules that ultimately led to its current freewheeling style.