|

→ February 2007 Contents → Column

|

Nuts & Bolts:

Taking Pictures vs. Making Pictures February 2007

|

|

|||

|

A long time ago, in the age of film, I wrote, "Rangefinders take pictures, and Single-Lens Reflexes make pictures." Now that there's a long-based digital rangefinder, the Leica M8, I'd like to change that a little bit.

Rangefinders help you take pictures and single-lens reflexes help you make pictures.

One of the most important differences between cameras is the viewfinder. When you lift a Leica to your eye, very little changes. There is a demagnification. Some bright lines define a rectangle within a viewfinder field that does not change regardless of the focal length lens you are using. For the most part this has all the thrill of lifting a piece of window glass to your eye. The advantages? Nothing is out of focus and unobservable. You can even see outside the edges of the final frame and see what's coming into that frame or what you might add to the picture if you shift the frame slightly. It's great for quickly taking a picture at the right moment when you are faced with a rapidly changing scene.

Each camera has its additional advantages. The long-based digital rangefinder, the M8, does an exceptional job of focusing high-speed normal and wide-angle lenses at their maximum apertures even in low available-light levels and with subjects of low contrast. There are a lot of autofocus DSLRs out there. Their performance under these conditions varies, but dim light and low contrast give all of them a hard time. And their focusing mechanisms must deal with both fast primes and quite slow zoom lenses. The balancing act of creating an autofocus system for these extremes can even result in a camera with two autofocus sensor systems, one that can kick in with fast lenses and one that does everything else. But to be effective in the real world, any of the systems that I am aware of don't take advantage of lenses faster than 2.8.

On the other hand, the rangefinder loses serious ground in the focusing olympics with long lenses – an arena, along with close-ups, in which the DSLR excels and which is extremely important to the news photographer.

The single most versatile camera is the SLR. It can take on a huge range of assignments.

There is no doubt that the rangefinder, once the king of the photojournalistic camera world of Cartier-Bresson, Eisenstaedt and so many others, has, justifiably, become more of a special purpose camera. Canon, Contax and Nikon (at one time all were producers of professional-grade rangefinders) have stepped out of the picture. Leica is late in producing a digital version of their rangefinder. They moved from a time in which the Leica School toured journalism schools and worked with students to a time in which Leica promoted boutique cameras with a selection of colored leather coverings and custom metal finishes. The number of young professional journalist who up until now were using film Leicas seems not to go too far beyond those whose photojournalist parents had given them their old Leicas.

While the rangefinder is now a specialty camera, it's a hell of a specialty. Without a mirror or pentaprism, it's small and quiet. It focuses and views accurately in low-level available light and rarely needs a flash. It introduces little or no vibration at slow shutter speeds. And it works in bright light, too.

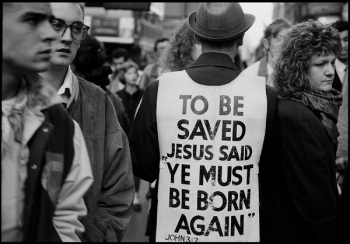

It's not an invisible camera, a candid camera or a concealed camera. But, it is a minimalist camera that does not call attention to itself. And in a relatively brief time, most subjects forget about you and you become a fly on the wall, albeit much larger and heavier than most flies. Outdoors, where there are no walls, nobody pays any attention to you at all - except Leica fanatics who run up, grab you and say, "Is that the new diggi?"

In the past I have mentioned that once at a state dinner in China one of my tablemates asked me what I did. I replied I was a news photographer and flashed my Leica. He laughed and in spite of the language difficulties made it clear that with my little camera I was an amateur. Next night, same Beijing government hall, I unveiled a motorized SLR and was immediately accepted as a professional. As someone who spends a fair amount of time annoying people with my cameras in public places, the ability to look like a silly, but not too threatening, amateur has always been a strong argument for using the Leica.

In the past, film rangefinders and SLRs were often used together, shorter lenses on the rangefinders and longer lenses on the reflexes. This maximized focusing accuracy in the days before autofocus and a broad selection of zoom lenses. Today it is far more likely to see one or two zooms on one or two DSLRs. The digital rangefinder becomes a camera that is primarily used solo in those situations it handles best – low-light and low-profile.

In the case of the M8, this is fortunate. In order to maximize image quality in the corners of the images, the infrared filter found in all conventional digital cameras is a thin one in the M8 and only partially effective. It does pass some infrared light. The only drawback from this sensitivity that I have seen is that some black artificial fabrics are rendered a warm brown. This means that if the final pictures are going to be run in color, pictures from the rangefinder and a DSLR may not match. It may look like your subject keeps changing their jacket in mid-shoot.

The disturbing thing about the M8 infrared sensitivity, and this is not the first digital camera to display this phenomenon, is not the color rendition of some windbreakers but that Leica was less than forthcoming about it. Either its top technical people or executives were ignorant of the situation or intentionally silent. Neither seems particularly positive in spite of the fact that I think most photographers would opt for the sharper image produced by the thin filter in front of the sensor. (Once the problem became well-known within the Leica community, the company announced that M8 owners will receive two free infrared filters in the lens size of their choice to rectify the problem.)

Leica has made one other decision that maximizes image quality. They have eliminated the anti-aliasing filter used by many digital cameras. Essentially, this is a diffusion filter over the sensor that eliminates moire patterns. I have yet to experience moire patterns with the M8. But eventually some scene with a closely spaced, repeating pattern like a chicken wire fence will produce moire and I'll have to take it out in Photoshop. In the meantime, I'll have sharp pictures.

There are very few carpenters that only have a saw. Most have a saw and a hammer (and a screwdriver). It's good to see that in the world of digital photojournalism we are getting more basic tools. A hearty welcome to the new kid on the digital block, the long base length rangefinder.

© Bill Pierce

Contributing Writer

|

||||

Back to February 2007 Contents

|

|