|

→ February 2007 Contents → Feature

|

PORTRAITS OF VIOLENCE:

The Gangs of Port Moresby and Suicide Bombers in Gaza February 2007

|

||||||

|

Introduction by Robert Pledge

For the past 30 years, the photographers of Contact have produced work in nearly every format and style, color and black and white, but there is one constant in our work: it almost always puts people at the forefront.

Kristen Ashburn and Stephen Dupont — American and Australian respectively — are to a great extent, I believe, emblematic of Contact's approach today and all that is right with our small agency.

Both Dupont and Ashburn have confronted this issue head-on, not merely on the front lines — where both have certainly been, in Afghanistan, the Middle East or Iraq — but through the unlikely form of portraiture.

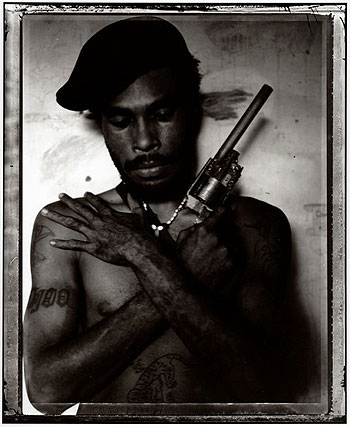

Plagued by 60 percent unemployment and chronic poverty, crime in Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea, in Oceania is rampant, earning the city a reputation as being one of the most dangerous places in the world. Much of the violent crime – armed robbery, rape, and carjackings – is committed by young gang members known as "Raskols." In 2004, Stephen Dupont infiltrated a Raskol community to document the individuals behind the facelessness of gang warfare. Building trust over several visits Dupont was able to set up a makeshift studio in which to photograph his subjects. The resulting portraits depict the "Kips Kaboni" or "Red Devils," Papua New Guinea's oldest Raskol group.

In 2002 and 2004, Kristen Ashburn traveled to the Israeli-occupied territory of Gaza. There she photographed shaheeds-in-waiting — those trained for suicide missions — and shaheeds-in-fact — casualties of the ongoing violence. Probing the cultural and religious influences behind the phenomena, she also visited martyrs' families, their communities, and explored their place in the region's tragedy. Utilized as an instrument of terror, such bombings, especially on public buses and in restaurants, have resulted in the deaths of hundreds of Israelis. Valorizing the concept of "martyrdom" among Palestinians youth, they have also influenced a new generation of shaheeds or "martyrs" who often die in emulation of their heroes.

Does this make them backward? Hardly. Actually it makes them modern. They are so contemporary that they have bucked the trend of digital photography. What's old is new again, and by utilizing this traditional aesthetic approach to portray violence today, they have kept what was always powerful about portraiture – its ability to confer recognition on an individual – while also inverting the form by giving recognition to people who don't usually get it. Whether it's the gang members in Papua New Guinea or suicide bombers in Gaza, these are people who more often than not are perceived, when perceived at all, as representative.

But Dupont's "Raskols" and Ashburn's shaheeds are not mere symbols. They are not representative. They are, the pictures tell us, individuals. People in brutal atmospheres of poverty, humiliation and despair, searching perhaps for revenge, maybe even truly psychopathic, but individual human beings just the same.

Does this make the photographer an advocate? Not unless one feels that some people should not be seen, should not be looked at, should be avoided like the plague. Which is exactly what many might think. This utter dehumanization, though, this "fear of contact" is probably the source of violence in the first place. It has always been my belief that being heard is a fundamental and inalienable human right. When defeated by linguistic or cultural barriers, this right can be rescued by photographers who offer in its place an equivalent right — the right to be seen.

Ashburn and Dupont are not afraid of contact. In both of their portraiture, the subject is also a participant. Instead of being "captured," their subjects are given the opportunity to express themselves fully through these photographs. Whereas typically, it is the photographer who points his weapon-like lens at the squirming subject, here it is the subjects who are armed.

People generally perceive courage in a photographer in relation to dangerous situations, to being under fire. But these images by two intrepid photographers were at least equally "dangerous" to make. Not only because both sets were produced in hostile environments, but because to look straight into the eye of one contemplating murder and mayhem, to attempt to communicate with the excommunicated, as it were, is inherently risky. "If your pictures aren't good enough, you're not close enough," Robert Capa once said. Dupont and Ashburn get close. They get inside. And to confront this type of grief, anger, despair, or pain takes, I feel, as much bravery as situations where violence is acted out.

So what do their images tell us? Well, in a sense, they don't tell us anything. It's the people themselves who talk to us. They look us in the eye with expressions of threat or dignity or confusion or questioning. Worlds away from the brutal violence of the Gaza Strip, or the crime-ridden streets of Port Moresby, there is still something we can recognize.

After 30 years, I've come to put my faith is such simple gestures. There are many dramatic photographs of war and unbelievable violence to be had with just a few clicks of a computer mouse. Most don't tell us much at all. Most get filed away like stills from a Martin Scorsese film, just part of our culture that treats violence as entertainment — mind-numbing, useless, and often downright destructive.

Stephen Dupont and Kristen Ashburn have succeeded in doing something better. Their images, staring into the eyes of our worst nightmare, can be truly chilling. But that's just as it should be.

[Please see http://www.contactpressimages.com/ for the photographers' bios and more images.]

© Stephen Dupont and Kristen Ashburn

About the PhotographersStephen Dupont was born in 1967 in Sydney, Australia. He began his photographic career working for Reuters in Africa. He has since covered conflicts throughout the world, including Kashmir, Indonesia, East Timor, Rwanda, the Middle East, Afghanistan, and Iraq. He is the recipient of several World Press Photo Foundation awards, and is the author of "Steam: India's Last Steam Trains" (Dewi Lewis Publishing, 1999) and "Fight," a four-continent project on wrestlers around the world (Marval 2003). His work -- including war photography, his portraits of the "Raskol" gangs in Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea, and his coverage of the 2004 tsunami in Banda Aceh, Indonesia -- has been widely exhibited. His images of American soldiers burning the bodies of dead Taliban in Afghanistan earned him a rare Robert Capa Gold Medal Award citation from the Overseas Press Club of America in 2005. He joined Contact Press Images in 1997 and is based in Sydney, Australia.Kristen Ashburn was born in 1973 in King of Prussia, Pennsylvania, USA. Committed to humanitarianism beyond the lens, while still in college she made five trips to Romania as a volunteer working with neurologically-impaired orphans, and in 1997 established an American chapter of the Romanian Challenge Appeal, becoming its first chairperson. In 2001, the year she joined Contact Press Images, she began to photograph the impact of AIDS in southern Africa. She has since produced essays on Palestinian suicide bombers, Israeli settlers in the Occupied Territories, and the aftermath of 2004's tsunami on Sri Lanka. She is the recipient of Canon's 2004 Female Photojournalist Award at the Visa Pour l'Image Festival in Perpignan, France, in support for her work on AIDS, and World Press Photo first prizes in 2003 and 2005. Her work on AIDS earned her a Getty Foundation Grant in 2006. She is based in New York City, USA. Robert Pledge is the co-founder and President of Contact Press Images. |

||||||

Back to February 2007 Contents

|

|