|

→ March 2007 Contents → Feature

|

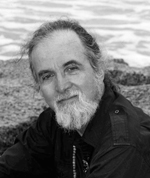

Appreciating Russell Lee

March 2007

|

|

|

Photographers, like actors, can be typecast. When you are the go-to person for a particular kind of job, it's an advantage. When you can't get the out-of-type assignments you'd like to increase your income and demonstrate your scope, it's a curse. The same thinking applies to the history of photography where even the greatest photographers are too often known for a particular style or subject, ignoring the broader range of their accomplishments. A few best hits oft repeated become our signature memory of their careers.

Photo history has typecast Russell Lee as a documentary photographer who photographed American life in the 1930s during the hard times of the Great Depression. That work was done for the Farm Security Agency (FSA), a federal agency to help displaced farmers that also documented them and other Americans as part of its mission. Working for the FSA earned Lee his place in the pantheon of photographers to respect and remember. However, typecasting, a self-effacing nature and limited distribution of his later work have resulted in a general failure to fully appreciate Lee's accomplishments, an array of visual insights that extend far beyond his work for the FSA.

Lee and his wife Jean, who traveled with him for many of his projects, donated his personal collection of negatives and associated files to The Center for American History at the University of Texas at Austin. The original materials for everything but his work for the government, some commercial work, and his color photography are included. There it has joined a growing photographic collection that documents American life and history. In 2005 the University of Texas Press asked CAH photo archivist and curator Linda Peterson to submit a proposal for a Russell Lee book project. The proposal was approved and Linda engaged the great curator and historian John Szarkowski to write the preface and me to write the introduction. Linda kept the plum job of selecting and arranging the photographs for herself with a lot of input from me, Roy Flukinger, and Dr. Don Carleton, the Center's director. This was a heartfelt project for me. Many Friday afternoons I had joined a group that drank Scotch and enjoyed Central Texas barbecue with Russ. I used his personal copy slides to teach about his work in my history of photography classes. In his last year Dr. Julianne Newton and I helped him review his files and determine their disposition. In his last hours I had a final conversion with this great photographer who was optimistic and forward-looking to the end.

Chronologically, the CAH Lee archive begins with nearly 40 35mm rolls of his earliest work from 1935-36, before he joined the FSA. He approached a far greater range of subjects than the famous sad street scenes of out-of-work men in New York City where he spent winters, and the desperate auctions of household goods in the Woodstock artist's colony where he lived in milder weather. His Contax I camera pointed to upscale life as well as the unfortunate. He managed interiors as well as exteriors despite the limits of slow film and no flash synch. The themes he continued to explore throughout his photographic life were established early including political life, street scenes, shopping, portraiture, personal and public spaces.

Frowning political speaker. Note his forefinger stuck in the watch pocket of his vest and the array of expressions on those behind him. This penetrating document was Lee’s earliest take on American political life, a subject he dealt with extensively during his Texas years. 1935/36.

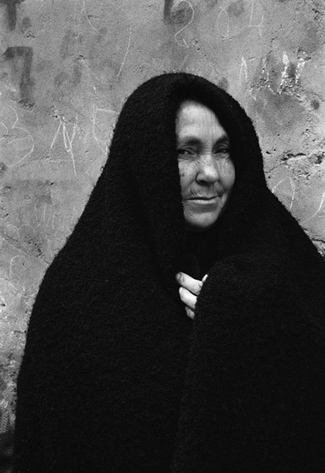

Old woman in shawl, Piazza Armerina, Sicily, 1960

He did reconnect with Roy Stryker, for whom he had worked at the FSA. Stryker was now working with Standard Oil creating an industrially motivated documentary project. This led Lee to commercial projects for oil and steel companies, travel to Saudi Arabia and Europe, and some of his finest large-format photography.

Two projects of special interest in the CAH collection are photography for the Study of Spanish-Speaking People in Texas (1949), and for a special issue of a University publication, Texas Quarterly, titled Image of Italy. He traveled through the country in the summer of 1960, from Sicily to the Dolomites, to provide over 150 illustrations. He was at the height of his photographic power. Italy was ripe with photographic potential. Scholar William Arrowsmith, who edited the volume of writing and photography, noted in his foreword that, "In a half hour's drive out of almost any city in Italy you can pass through three or four successive centuries, all of them simultaneously alive…" Both the Study of the Spanish-Speaking People and Image of Italy files provide a rich treasure of little-known photography.

Hats on chair, Brazos River Authority Tour, 1956

For a privileged few the 1930s Great Depression did not disrupt the good life. A close-up in this series of the facial artist indicates that the subjects acknowledged this photography, although it seems candid. From the beginning Lee sometimes worked with what photojournalists later called the “posed/unposed” method in which the subjects cooperated to give natural-looking pictures by following their normal routines for the camera. 1935/36.

Lee was an active photographer for more than three decades after the FSA. There has been one significant survey of his career (F. Jack Hurley, 1978), long out of print. Linda Peterson and I are grateful for the opportunity that the Center for American History and its supporters have provided to offer a broad selection of Lee's personal files in Russell Lee Photographs, all of it beyond the FSA, much of it not known to the viewing public.

For more about The Center for American History go to: http://www.cah.utexas.edu/. Information about their Photography Collections is at: http://www.cah.utexas.edu/collections/photography.php.

The complete series of negatives Lee shot on assignment for the Study of the Spanish-Speaking People of Texas is at: http://www.cah.utexas.edu/ssspot/.

More about Russell Lee Photographs is available at the University of Texas Press: http://www.utexas.edu/utpress/.

© J.B. Colson

|

|

Back to March 2007 Contents

|

|