|

→ April 2007 Contents → E-Bits

|

E-bits:

Technotopia April 2007

|

|

|

One nice thing about living in a university town is the constant flux of discovery and innovation, ideas and creative expression. Those of us who have one foot in the world of education and the other in professional life are privileged if we have the opportunity to live on the periphery of a university campus where vibrant and aggressive pursuit of information and analysis is a normal, everyday function. Over time, major collections and archives from significant contributors tend to amass at university museums and history centers. Heretofore, it has been the case that people living close to centers of power on the world stage such as Washington, London or Paris find themselves engaged in every nuance of unfolding events, whereas those in the hinterlands, to borrow a popular phrase, "not so much." Scholars striving to place events in historical context often have to wait decades for data to accumulate; hence historians, authors and researchers come in droves to the catalogued archives at academic institutions to realize that goal. This long and drawn-out process may still be the case, but -- and please feel free to disagree -- not quite so much.

As technology effectively shrinks the world into a "global village," everybody everywhere has a chance to pay attention to the lightening-fast reports of stunning events and mundane minutiae emerging anywhere in the world. In one second, Google can catalogue information faster than the entirety of past, present and future librarians could ever accomplish by hand. If Alan Greenspan can make a casual comment that causes an immediate and significant dive in the financial markets around the world, we have to know that we're interconnected to an astonishing degree. Can any of us really be surprised there is a noticeable effort to take control of free speech, release of information, and dissemination of the news? And is it any wonder that the news, at least here in the states, has largely become infotainment, with very little info attached? JibJab has created a humorous video along these lines called "What We Call the News." Click on the photo of David Brinkley, Walter Cronkite and Edward R. Murrow for a lighthearted examination of the subject.

It is hard to recognize something one has never seen before. So, most of us have been wholly unprepared for change occurring at warp speed -- as has been the norm for the last 6 years. Really, though, rapid change has been upon us since the end of World War II, and who does not recall our grandparents opining with a good amount of dismay about the younger generation and new-fangled things. One completely new-fangled thing, the personal computer, made its debut in 1977. Before that, and as recently as 1974, a computer required the physical space of an entire building. However, members of today's under-30 set were born with a computer mouse in one hand and a credit card in the other, and by age 5 were completely savvy about technology and product information. If we haven't seen today coming, then we haven't been paying attention. I see a lot of bumper stickers saying similar things.

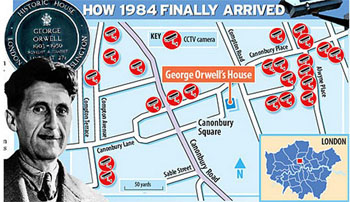

One person who did anticipate our lives in a fully-realized technological age did so in 1949 in his book, "1984." George Orwell was so ahead of his time that he predicted the futureworld of today would arrive even sooner than it has by almost a quarter of a century. Instead of 1984, here we are in 2007, and ironically the fictional Big Brother that he imagined is in fact watching Orwell's own former home in London via no less than 32 surveillance cameras within a 200-yard radius of the house on Canonbury Square. British citizens now enjoy (or endure) being caught on camera on average about 300 times per day. Orwell's prescient view of the future was dystopian; hence, every one of us learned by reading that book to fear total surveillance. However, might it instead turn out to be utopian? We could hope so, but if the brutality elsewhere in the world accompanying total but allegedly benign surveillance at home is any indication, we have a way to go before Utopia arrives. Read about Orwell's neighborhood, and then click on the photo below to watch a video by David Scharf and Stephen Taylor called "Big Brother State" that has a particularly dystopia-flavored warning.

During the nearly three years of E-Bits columns in The Digital Journalist, we have not repeated a video or photographic display, with one exception. However, if ever there were to be a repetition, an amazing video comes to mind from the July 2005 issue. EPIC 2014 is an otherworldly animation about the consolidation and future of the media. It was created in 2004 by Robin Sloan and Matt Thompson, music by Minus Kelvin, and presented under the auspices of The Museum of Media History in Tampa, Florida. The original video has been updated to a new version, EPIC 2015, which takes into account things not yet anticipated in the original. This fascinating and seductively entertaining work bears not only re-presentation but also new consideration.

It is highly unlikely that anyone can accurately predict what the world will be like in 2015, though EPIC 2015 offers a feasible proposal, a sort of Technotopia, to coin a phrase. No doubt all previous visions will give way to a new reality as yet unimagineable. Orwell's 1949 projection 35 years forward to a dystopian future was based in large part upon the then-recent horror of WWII and a certainty that new, abusable technologies were coming. Few can embrace uncharted territory fearlessly, but Kevin Kelly reminds us in his book "Out of Control" that just when we think all is lost to permanent chaos or total pandemonium, amazing systems of self-regulation and balanced sustainability emerge, and they do so when we least expect it.

Though the jury is out about what's ahead, I leave you with a quote from "Out of Control": "No one has been more wrong about computerization than George Orwell in '1984'. So far, nearly everything about the actual possibility-space which computers have created indicates they are the end of authority and not its beginning." In other words--and I hear it said often--the Internet is going to save the world.

© Beverly Spicer

|

|

Back to April 2007 Contents

|

|