|

→ May 2007 Contents → Column

|

A Letter From New Orleans: Cutting Loose

May 2007

|

|

|

After my recent description of the deaths of two strangers, and the effects those occurrences had on my own post-K life, I was reminded by a few New Orleans stalwarts that over a decade ago I had written of another death, also tied to the same location. The occasion was the celebration of the passing life of a close friend, and the few pages I wrote were circulated only to those who knew him.

But I was told this week that his family still keeps their (and my) memory of him alive on a Web site: http://www.pudbrown.com/index.html#summit.

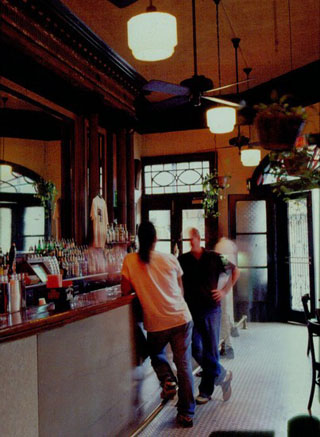

Home to New Orleans' oldest stand-up bar, Tujague's has been a favorite Big Easy watering hole for over 150 years.

That said, I offer you a story about death, from a cookbook.

A New Orleanian would not find it odd that a discussion of living in the City should begin with food and a funeral. Life and death hold each other fondly in these neighborhoods, two ageless lovers engaging arm and arm to move in a slow, sexy tango, bumping and grinding on the dance floor, taking turns leading. Maybe that's why so very few things bother those of us who live here. Different sexual proclivities? Have at it. Unfamiliar racial characteristics? Hey, we all look a little peculiar 'round these parts.

Odd religious identity? Child, only five years ago in the Faubourg Marigny there was an Irish Catholic church, a German Catholic church, a French Catholic church, and a Creole Catholic church, all within a dozen blocks of one another, and all getting along just fine for the last century or so.

The Palm Court Jazz Cafe in New Orleans' French Quarter is one of the few remaining bastions of traditional jazz.

So, dying is not as bad here, they tell me. There's always music. The food is good. And there are cocktails available up to the moment of departure.

I was having just such a beverage in the company of friends when this particular experience with afterlife began. I was at Tujague's, and I myself was quite alive.

* * *

Tujague's Restaurant holds New Orleans' oldest stand-up bar, the long cypress planking a hangout for off-duty waiters, retired bookies, French Quarter portrait painters, beer truck drivers, writers of all ilk, R&B musicians. And the inevitable tourists.

The bar is comforting and familiar, but the food that emerges from the tiny kitchen lets you know immediately that you're home. I have always believed that there is a singular synapse between the stomach and the soul: the term "gut reaction" seems perfectly descriptive to me. And here in New Orleans the distance between the two seems to shrink. It is readily apparent to residents that the occurrences of daily life and the food consumed during the actual living are directly connected.

A Creole table d'hôte menu is served seven nights a week at Tujague's in New Orleans' Vieux Carré.

My original idea was that, to properly appreciate the food, you must digest the place in which it originates.

And thus, Tujague's.

In spite of the extremely limited selection of entrees that are listed daily on the kitchen's blackboard – only the entree allows choices in its traditional Creole seven-course table d'hôte menu -- regulars know they can always order the incredibly garlicky -- four full heads of garlic used on a huge single bird -- poulet bonne femme, the only off-the-menu item the kitchen will prepare.

Four people can make a good meal off this huge dish. The solitary consumption of a flavorful "good woman" from Tujague's (the process requires a doggy bag and two days of additional meals) is one of my few remaining vices, and the possible cause of a recent weight gain. On busy nights, Steve Latter, whose family brought the house back into international prominence in the last 21 years of its 151, will only make the dish if you call in a good three hours ahead with your order. Or 15 minutes if you're a regular. Which I now seem to be.

I first placed my foot on Tujague's brass rail 42 years ago. That number now seems so extraordinary. On the day after my high school graduation, I would have never believed I would one day find myself 60 years old, standing in the same place. But sure enough, here I am, looking at a grey-haired, bearded fellow with bags under his eyes and over his belt. He seems a bit defiant, framed in the 14-foot-tall reflected universe that runs the entire length of the large room. The mirror that holds this elderly gent was itself brought over in the hold of a sailing ship in 1856 after already gracing a Parisian Bistro for 90 years.

Everything in this neighborhood is old. Vieux Carré does not romantically mean "French Quarter," as so many visitors believe. It means "Old Square." And there I wander, appropriately enough, as old and square as they come.

A plate of garlicky poulet bonne femme, an off-the-menu Creole specialty at Tujague's.

Even the black-and-white tile floor's surface rolls in noticeable grooves like the rising swell of a morning sea, the result of decades of dockworkers, sailors, and butchers making their way to the bar to stand and raise glasses in camaraderie. This is indeed the sovereign "standing" bar of the City. The one large table, available for seating only in the latter part of this century, is made of brass hammered into the shape of a painter's pallet, and is positioned under the room's single unshuttered double window.

Age suits the place, and me, I have decided, generously to us both. The details of setting are important. It's the pleasures inherent in such small matters that make life worth the wretched trouble of passage. Which brings me back to where I started: a particular interconnection of mortality and sustenance.

I was at the Decatur Street end of the bar late one particularly hot Tuesday afternoon. My workday had been filled with stops, starts, bobbles and twists, my brain and patience both taken well beyond their natural limits. This is the norm in a business where electrons are manipulated for public gratification.

But my workday was over, it was the Happy Hour at Tujague's, and Noonie (a direct descendant of the original Guillame) was managing the house.

The Rebirth Jazz Band leads a traditional New Orleans funeral procession.

Jake nodded toward his boss, indicating deference to management in such matters. Noonie obligingly moved the woman along, aiming her toward the back staircase and the balcony overlooking the street with a single concise sweep of his own forehead. She went up the steps in quick bounds.

I heard a very active musical wave approaching and looked out to the sound. Near the street's central yellow lines, several friends of mine were walking in step preceding a brass band. Mike Stark, the president of the New Orleans Maskmaker's Guild, was foremost, directly in front of a pair of trombones. He spotted me through the now open doors of the bar and waved at me to come into the thermal waves of the street and join him.

I hesitated at returning to the heat, but decided to step outside to evaluate the possibility.

It was indeed one more very, very hot day in New Orleans.

I am just stepping outside for a look, I told myself again. And immediately found myself pulled into clarinetist Pud Brown's funeral parade. The white handkerchiefs were waving. The umbrellas bouncing. I couldn't resist. I knew Pud had died and I cared about him, even if I had talked myself out of going to the ritual church portion of the service. And I had admired and loved the mourning Mike for years.

Mike Stark, the huge, bald, red-bearded fellow in the caftan, was as much an historic figure in the French Quarter as St. Louis Cathedral. If Mike needed the comfort of a parade to put Pud away, I would certainly join him, and share the burden. I owed them both that much. I saw Jake the bartender making a concise hand signal as I headed out without a word. Jake understood about such matters.

The procession was Walking to a dirge when I fell into step between Mike and the forward horns of the band. "Just a Closer Walk With Thee" was the tune, and because of the number of veteran paraders involved, the synchronous movement of the group was heartbreakingly beautiful. For those who have not witnessed this death dance, the term "Walk" does not at all describe what happens during the slow tunes in a funeral march. "Just..." right foot steps forward. Pause. "... a closer..." swing the weight forward over the right foot and bring the heel of the left foot up, pointing backwards with the left toes. Pause. "... walk with thee..." left foot forward, even with the right. Pause two beats. Repeat in reverse order.

Once the rhythm asserts itself and the steps become automatic, the Walk is as powerful and emotionally affective a way to move in a group as any ever devised by upright man. The sight of a cortege of this size, a wailing band proceeding a whole block of family, friends and admirers, five or six hundred strong, slowly lifting up, moving forward, and settling back down in front of a creaking horse-drawn catafalque, is hypnotic. The spectacle drives many onlookers, who have no idea of the identity or worth of the departed, to uncontrolled sobbing.

That day tears had been rolling down Mike Stark's face for some time. The small vertical line of salt on each cheek was testament to the fact that he did not care to stop them. I cried, too, even though I knew Pud himself didn't care much for tears, just because of the beauty of the procession and the emotion of the moment. I suppose he would have excused me for that. He'd played hundreds of funerals and would normally be playing his horn up front of the very box that now carried him.

Pud was one of the premiere traditional jazzmen in the Universe. The Universe, by trad standards, may rightly be defined as the twelve block-by-nine block area that makes up the French Quarter in New Orleans. Rampart Street to the river, Canal to Esplanade. Pud had moved residence not long before his death to be closer to his new musical home at the Palm Court Cafe, where he played often and long. He enjoyed having regular, long-term gigs, and never grew bored of the songs he played over and over.

We had met some 10 years earlier, when I telephoned him to request his participation in a sunrise set of turn-of-the-century brothel music I was staging. A friendly spirit even to strangers, he asked me over to discuss the gig in person.

Pud was then living on St. Peter Street, in one of Tennessee Williams' old habitations. His seven rooms were stacked wall to wall and floor to ceiling with music, records, and archeologically significant instrument parts. It was impossible to see across the width of any of the spaces, and passage was accomplished by moving carefully though blindly through twisting narrow gaps between the tall columns of musical materials. Avalanche was a very real prospect. An unmoving cloud of sparkling particles was suspended in the few shafts of sunlight that pushed their way through the torn and dusty lace curtains at the balcony end of the third-floor apartment. The very air was thick with the music that had been played and the stories that had been told within the walls.

Physically you could tell that Pud had been down a long road, too. His large body sagged and his ruddy face rolled under a shock of white hair, though behind thick glasses his eyes were as lively as a teenager's. He had a smile that would travel through time and space, and make you grin a week later in remembrance.

Pud and I sat on his bed to talk, that being the only clear spot he could offer for seating. The few chairs he had were piled with sheet music to such a height that the top of the heap leaned against the wall near its crown molding. He slept in the narrow stairwell, on a frayed army cot canopied with an oxygen tent. He wasn't well, even then, and required the pure gas to give him rest. But the space around that 30-inch-wide bed was full of the happy detritus of a life spent joining harmony, traveling melody, and smiling at the ladies. He had a gentle, quiet voice that somehow lightly carried great weight, very much like the breathy sighing of his horn. He was not worried about the condition of his life or living. Everything was as it was supposed to be.

Nothing much bothered him on the bandstand, either. He made himself comfortable doing the job for which he was born. I found that out when we finally did the "brothel" film shoot, documenting an hour of historic bawdy music from the turn-of-the-century heyday of New Orleans' notorious legal red-light district, Storyville.

Pud had a habit of slipping his false teeth out and hiding them behind his left shoe while he rested between solos. I only noticed the teeth on the floor while in the last throes of post-production editing on the show, and had to go to great lengths to assure that the show aired on American televisions with most of the dental solos removed. In his latter years a patron bought him some better fitting teeth, but he'd grown accustomed by then to drifting off while the horn wasn't in place between his lips. He'd sit open-mouthed, staring into space, humming the tune while blowing cool air over his gums. Bands learned it was best to keep him busy and the teeth in place.

Pud Brown was a gentle, caring soul off the stand, and a bearer of the mellow winds of the heart when on. Which accounted for the large turnout at his funeral.

When I joined the parade, pallbearers had already "cut the body loose" -- taken the coffin out of the horse-drawn hearse and hefted it in the air three times -- in front of the Palm Court to start the parade. This is traditionally done when the cortege passes a spot favored by the deceased.

The bandstand in the Court had definitely been Pud's idea of an earthly heaven.

Now I walked beside Mike the maskmaker in the procession through four long tunes, strutting to the fast numbers and Walking to the slow. The coffin wove its way back and forth through eight blocks of the Quarter, then eastward across Jackson Square in front of the Cathedral, until it finally passed though Chartres Street one block above Tujague's, on the parade's last leg toward the cemetery. The route allowed me to return to my spot at the bar. And my drink.

Jake, the quintessential New Orleans bartender, had naturally kept my beverage chilled and waiting for me, even though he was unsure of my return. A good thing, too. I'd worked up a sweat, as happens with both temperature and humidity just dropping from the century mark, and not a breath of air stirring. I drank my back of ice water at a gulp, then toasted the departed Pud with a cool but not cold neat whiskey, and thanked him for the afternoon's soul-stirring Walk.

On a sudden whim, I pulled a bill from my pocket and stuffed it into the gaudy maw of the video poker machine that crouched against the wall beside the head of the bar. It was a fiver, but I bet the wad on one hand. As a matter of course I do not gamble, but will infrequently -- usually when I am in a pique -- put a dollar into one of those machines looking for the reassurance of a crystal ball or horoscope. I want someone, anyone, to tell me definitively if the future is looking good or bad.

So I rather enjoy letting the gaudy metal box sort through its pile of electronic innards and tell me whether I've a positive roll going, or if I should be more on the defensive. I figure that's at least as good a method as consulting the medieval used-car astrological forecast that is carried in almost every otherwise respectable daily newspaper in America. And unlike the machines, the journalists never ever give you your money back. In any case I normally only bet a dollar, not much more than the cost of such a paper.

But on this day a five came out of my pocket, and without hesitation a five went into the machine. I bet the entire amount as a solitary unit of haruspication. It was the right thing to do -- spread the entrails of the day and look for a message. I knew that my impulsive behavior was sparked by the emotional energy I had just absorbed from Pud's funeral, and somehow I felt this a necessary finale, or purgative.

Tell me what it means, even if it's bad.

I pressed the "Deal" button. There were four bell-like dings, followed by a great deal of quasi-musical noise.

The screen announced a win of one hundred dollars on my investment of five.

It was not my money. I bought the bar a round and a double order of bon femme for whomever wished to eat. After tipping Jake, I had my original five dollars left.

Pud was a generous sort, to the very end.

© Jim Gabour

|

|

Back to May 2007 Contents

|

|