|

Afghanistan: On the Edge of a Precipice

June 2007

|

|

|

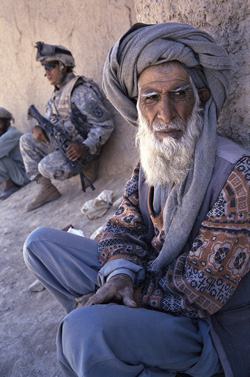

As his village is searched, an old Afghan man sits next to a U.S. Army soldier in Mani Kheyl, Afghanistan.

Contemplating the "no way" of the police station superintendent at the border, I sit for a few hours in the no man's land between the Jordanian and Syrian borders. I do know a plane is leaving from Alexandria for Kabul via Sharjah so I cross all of Jordan, the Red Sea and a large part of Egypt to arrive at a small and empty airport. "Where's the plane?" I ask. "It will come soon. Insha'allah." Even though I have a deep respect for all religions I hate hearing the two words "soon" and "Insha'allah" together. Meanwhile, a merchant pounces – he wants to sell me something: tobacco, chewing gum, drinks…. Although he has at the very most 20 items, he's saying he has everything I want – but at 10 times the normal price.

Major Innis of the Canadian Army stands in a warehouse once used to dry grapes but more recently used by the Taliban as both a strategic and defensive bunker because of its small openings. Afghanistan.

In Sharjah airport 50 Koreans join us. I ask myself if I'm on the right airplane. All the women have the same green and blue scarves on their heads, wearing them like a veil, and the men all have cameras as big as mine.

A few days after my arrival in Afghanistan, I learn of a thousand evangelist Koreans who arrived to spread a "culture of peace" in Afghanistan by organizing rallies and football tournaments. The Afghan government finally asks them to leave. A few local religious leaders said evangelists were a provocation.

A small shop on the road between Jalalabad and the Pakistani border of Afghanistan.

The many weapons became the way I passed time, walking through the streets of Kabul if there was nothing worth watching, I would look at the different kinds of AK-47s--owners always customize Kalashnikovs. I really hate weapons, especially since four M-16s (an American weapon) were pointed at me for a full 10 minutes by Palestinian militants from the al-Asqa Brigade while I was at the Balata refugee camp next to Nablus. They kept asking me if I was a Jew or a spy.

Over the three months I had enough time to see this poor central Asian country falling into a new period of instability. At the end of my journey suicide bombings happened every day and the feeling of insecurity grew worse. Trying to meet the Taliban is nearly impossible and if it does happen, it can be either really dangerous or an act--just some farmers deceiving us to get some money. So I decided to go with the American troops to see what was going on in this new kind of war between a coalition of Western countries exporting their democracy and some insurgents who do not accept the presence of foreigners on their homeland.

During "Operation Medusa," American and Afghan soldiers fear an ambush while patrolling in Pashmolu near Panjwai, 15 miles west of Kandahar, Afghanistan, on Sept. 21, 2006.

While the hunt for Osama bin Laden and his network seems to have been forgotten or abandoned because there was no result, a medium-intensity war continues in Afghanistan. During a 12-day patrol in the Paktya Mountains in the south of Tora Bora searching for "the enemy," Captain Stiemke of the 3rd BSTB of the American Army explains the new (and real) strategy of the Western armies in Afghanistan. "We are no longer aiming at fighting the enemy because if some of our men are killed it's very bad for our image in the United States. Vietnam taught us a lesson. We are trying more to get the bad guys to use their resources to flee. In this way, they will become weaker. For that, we patrol with a large number of armored vehicles, heavy weapons, mortars, in order to get them to stop attacking us. The American people don't care if we spend a lot of money--as long as there are no dead bodies."

Although I met a lot of helpful guys in the four armies I was with (French, American, Canadian, Afghan) I feel this war is useless. There are background problems inseparable from the stability of this central Asian country where war has never really stopped for more than 25 years. The two most important problems are self-evident and explain the long and growing queue of potential suicide bombers. The rate of unemployment estimated by the Afghan Ministry of Labour reaches 35 percent and this is probably an underestimation. Poverty is growing as corruption becomes the paradigm of the everyday life of the Afghan people. One example among many others: at the entrance of public hospitals I had to give baksheesh to get the underpaid doorman to let me in. The same happened at the airport on my last day as I was returning to France. Five years after the entry of the French, the Germans, the Americans, the Italians, the Turkish and the Canadian forces (to name only the most important ones), as well as the establishment of a large number of NGOs, Afghans go to bed on an empty stomach.

© Philip Poupin

|

|

Back to June 2007 Contents

|

|