|

→ June 2007 Contents → Book Review

|

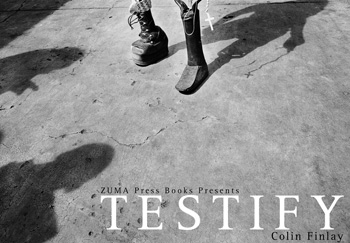

"Testify"

By Colin Finlay ZUMA Press Books: 2006

Reviewed by Marianne Fulton June 2007

|

|

Colin Finlay's biography identifies him as "one of the foremost documentary photographers in the world." If you have any doubts about that, open his new book, Testify. Here are more than 100 black-and-white images of dignity and devastation selected from 17 years of photographs and essays.

This powerful retrospective presentation was picture-edited by Antonin Kratochvil, with the final book design by Scott Mc Kiernan, ZUMA Press chief executive and founder. The introduction is by Karen Sinsheimer, curator of photography at the Santa Barbara Museum of Art.

Mc Kiernan, Kratochvil and Finlay have created a beautiful, concise, adamant statement about the world of which we are a part but ignorant about – or perhaps we just feign ignorance. To take a career's worth of images and produce one sustained shout of recognition – the soul of a man's work – is a remarkable feat.

Boys huddle together, smoking a cigarette for warmth on Jan. 1, 1995 in Bucharest, Romania. The boys are AIDS-infected castoffs who came to die at the "end of the world." Children suffered most at the hands of Romania's Communist leader Nicolae Ceausescu. He made abortions illegal. While the population did increase, many of the children were abandoned by their families at state-run orphanages. Ceausescu also refused to acknowledge the presence of AIDS in the population. He forbade testing of the blood supply. Use of shared needles in transfusions for orphans resulted in Romania having half the cases of childhood AIDS infections in Europe.

He graphically describes what he found in the "apocalyptic landscape" of Kilgaly, Rwanda, after the 100-day massacre. His words picture the scenes very much the way photographs documented the Holocaust. At a church where 10,000 people were murdered: "Even before I'd reached its doors, the smell took hold of me. … Decomposing bodies, some with flesh, some without, lay everywhere, in positions of tortured agony." In smaller rooms, "bodies were stacked like cord wood, packed to the top of the doorways, spilling out of the window frames. Hands, arms, feet, skulls, all piled one on top of the other." At the end of this experience he found that his childhood in Scotland seemed far away and imaginary. "I left everything that I thought I was and knew behind. Rwanda created a scar, like the puncture marks a vaccination leaves on a child. It is now my past."

Early in his career Colin Finlay asked a seasoned photojournalist with him in Haiti if it ever becomes easier to confront death and human suffering. No, he replied, "it gets harder and harder. It means my work isn't getting out there enough. I'm not doing enough. I'm not working hard enough."

Finlay has been in hard and brutal places and finds that he feels tremendous guilt when he can't place his work. He has been to, for instance, the "end of the world" in Romania where children go to die alone and horribly as a result of AIDS-tainted blood provided by the same government that now rejects them. Also to the "City of the Dead" in Cairo where children suffer, working six to seven days a week for 10 to 12 hours a day. They labor to make bricks or roofing tiles for their own fathers and uncles who did exactly the same as children in a cycle that has persisted for generations – no one family raising itself out of poverty. As Finlay writes, "It's not about me; it's about the people who've entrusted their lives to me." For a passionate photographer who wants to enable people to speak through his pictures this is a moral dilemma.

Young boys caked with brick-making mud in the "City of the Dead" in Cairo, Egypt. They work 10-12 hours a day, seven days a week. Child laborers are the objects of extreme exploitation in terms of toiling for long hours for minimal pay. Their work conditions are especially severe, often not providing the stimulation for proper physical and mental development. Many of these children endure lives of pure deprivation. Mandatory Credit: Photo by Colin Finlay/ZUMA Press. Copyright 2005 by Colin Finlay

Testify is also a cry from the heart of the photographer for us to look at what is specifically happening and to do something to alleviate the suffering and hopelessness.

Visit ZUMApress.com, zReportage, and Colin Finlay's Web site colinfinlay.com to see the extended stories. For copies of this book see ZUMApressBooks.com.

Fulton is the former chief curator of the George Eastman House International Museum of Photography and Film; senior editor, The Digital Journalist; and author of the book "Eyes of Time: Photojournalism in America."

|

Back to June 2007 Contents

|

|