|

|

|

|

|

|

THROUGH A LENS DIMLY LIFE

BEFORE DIGITAL The first time I ever heard about digital photography was at a National Press Photographer's Association seminar in Boston in the early 1980's. The Boston Globe, or maybe it was the Boston American, gave a demonstration on how they were able to get late breaking spot news into their paper by using the newly developed Sony Mavica which digitized the image onto a floppy disc. The image quality of the time was not great, but it did get pictures in the paper. We've certainly come a long way since that initial technology. Sleep was slow in coming, that night, and my brain was churning with other ideas about how far the technology has come since I first started seriously considering photography as my life's career choice. For example; I realized that there are probably more photographers out there who have never used a hand held exposure meter than there are photographers who have used them. Jeez!

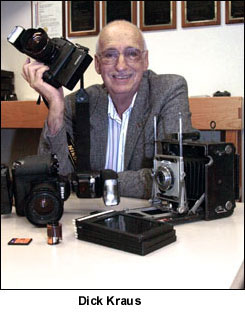

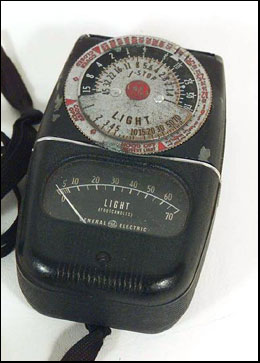

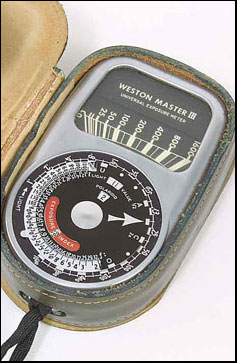

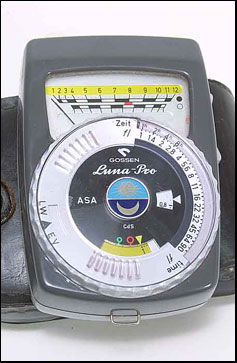

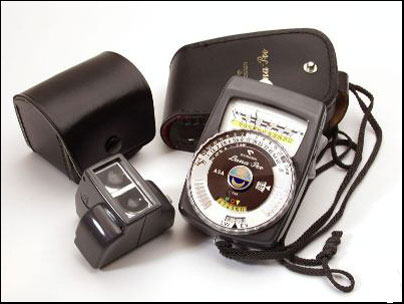

The cameras of that day didn't have the dandy little amenities of today. There were no scene setting electronic functions that would decide if you needed fast shutter speeds for sports or slow shutter speeds for greater depth of field. Electronics of any kind hadn't made its way into cameras. Everything was mechanical; from winding the film and shutter to exposure adjustments. The shutter was a spring driven device which could have it's speed changed by turning a dial which placed more or less tension on the spring. The aperture of the lens was also mechanical. You would turn a ring on the lens barrel which would widen or decrease the circumference of the iris diaphragm in the lens. Each adjustment worked independently. This was a cumbersome and time consuming procedure. The hand held meters were bulky and added to the clutter in your equipment bag. If lighting conditions changed while you were shooting, you would have to pull out the hand held light meter and then make the mechanical adjustments to your camera. At events that drew a large media presence, the photographers were usually set up all the way in the back. Many times the light differed from where we were to the subject so it wasn't possible to get a good meter reading. One of us would usually work his/her way down front and make a reading from there. He/she would then shout back what his/her meter read for the rest of us. While we were always very competetive, in things like this we always cooperated. My first meter was a GE. I think it cost about $19. I moved up to a Weston Meter when I started shooting professionally. That cost me about $32, if I remember correctly. My last hand held was purchased for me by Newsday and it was really a beauty. I think that one cost around $200. But, it had an adaptor that would change it from Reflective to Incident and another attachment that would turn it into a very accurate spot meter.

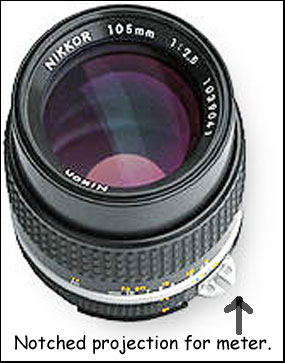

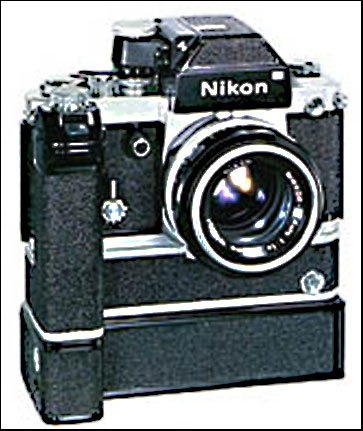

Shortly thereafter, Nikon came out with a new model with a built in exposure meter. It was the Nikon Photomic F and there was an exposure meter built into the prism assembly. Believe me when I tell you that it was quite primitive when you consider what we have today. This early attempt turned what had been a nice, compact Nikon F camera into something rather clunky. That nice, slim and trim Nikon F just kept getting bigger and heavier, after that. And, there was nothing automatic about it. The camera itself was still a very manually driven piece of machinery, with exposures set with a shutter speed dial and the lens with an aperture ring. But, you had all the features of the hand held meter now built into the camera.

Motor drives became a standard part of the camera body. The down side of the motor drive was that most photographers began shooting "movies." They would press the shutter button and hold it down until the film ran out. Photographers no longer waited for that "magic moment" of peak action; relying instead on the mindless robot of the motor to capture that moment somewhere on the roll.

Personally, I, and a few others, liked to retain control of our art, and disdained using the continuous mode on the motor drive in lieu of the single frame setting. This way you could keep your attention focused on the subject and not have to worry about sticking your finger in your nose or knocking off your eye glasses when you thumbed the advance lever to wind the film and shutter for the next shot. Later model cameras eventually had the motor drive built right into the camera body and the manual wind lever went the way of the Dodo Bird. This created some measure of consternation when news photographers were once again allowed to photograph in the courtrooms. Judges objected to the loud and continuous clacking of motor driven cameras which drew attention away from the lawyers, judges and witnesses. Some camera manufacturers introduced "Silent Modes" into their camera drives. It would dampen the impact of the mirror and slow down the winding of the film, but it won the approval of the judges. Thankfully, I fell asleep that night, before I could start thinking about the changes in flash equipment. Good grief! I would have been awake the entire night. Briefly, I'll mention that I started my newspaper career using flashbulbs. Hey, it could have been worse. Who remembers flashpowder?

OK. Flashpowder had pretty much disappeared from the scene by the time I entered the business. But, we were using flash guns and flash bulbs of various sizes when I started at Newsday.

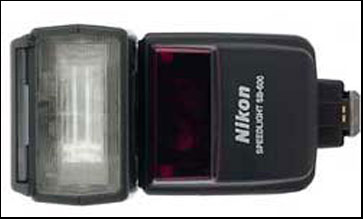

Eventually we got around to electronic flashes and the latest ones, like the Nikon Speedlight shown above, were dedicated to the camera through the hotshoe and then the camera and flash did all the thinking for you. I frequently bitch about the "Good Old Days" in my journals. How about darkrooms? When was the last time you worked in one of those claustrophobic and foul smelling closets? Would I ever consider taking a trip back to those halcyon times? Hell No!!! I will say that photographers back then had to pay more attention to details because the equipment didn't do any of the thinking for you. Photographers shot far fewer exposures and the ratio of good photography to crap was much higher. But, if today's shooters would use some of those early techniques, then all of the current state of the art technology would free up the photographer from mundane tasks like winding the film/disk and shutter and placing a fresh bulb in the flash gun and calculating the exposure. Now he/she can focus his/her concentration on the image in the viewfinder and wait for that "magic moment" to happen. I can't

wait to see what's in store for us next. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||