|

Children of Conflict:

Belfast July 2007

|

|

|

He had a finger cut off on both hands; he had been shot through his wrists, knees and ankles. A couple weeks later the paramilitaries who had done it returned to apologize for having mistaken his identity. The first time I had photographed him he was an 8-year-old schoolboy on a playground in West Belfast in 1981.

I returned to Belfast, Northern Ireland, to once again photograph, shoot video of and listen to children I had randomly photographed in 1981. They are part of my project entitled, Small Arms: Children of Conflict that encompasses four continents and eight countries.

Falls Road, West Belfast, Ireland: Damien Marley, 6 years old, plays on the remnants of a bus that was firebombed the night before during rioting in October 1981.

Children suffer the most during conflict and this reportage is being done in the hopes that the viewers will reflect upon the implications of political and economic conflict, war and racism as it pertains to those who suffer most and have the least control over their lives, the children.

To find my first group of previously photographed subjects I asked the Belfast newspapers to run articles and photographs about the project. Five articles were run and virtually all the children I photographed in Belfast in the '80s were found and or accounted for. The articles published along with my original photographs and the video I recently shot have generated interest from two UK production companies.

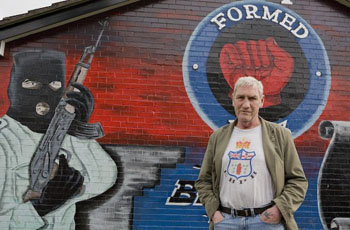

East Belfast, Ireland: A mural of UFF Ulster Freedom Fighters, a Protestant paramilitary group formed in 1973. Man in front of mural lives in the neighborhood and remarked to me, "There is still a lot of pain .... We hope for the best and prepare for the worst." He preferred not to give me his name. May 2007.

The search thus far has turned up a fascinating variety of stories about how these children have coped with their situation and what has transpired in their lives as adults. Some have committed suicide, many have been imprisoned, and one became a millionaire and owns radio stations in Spain.

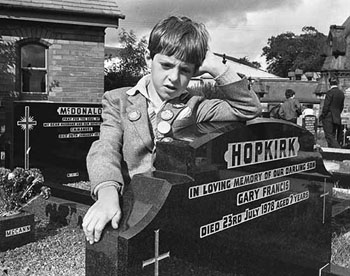

Paul McNally, 7 years old, attending IRA commemoration at Milltown Cemetery, West Belfast, Ireland, Sept. 1981. At the time his brother and father were in prison for political offenses.

It turned out the picture was not of his son but he brought up the fact that he was a boxing coach and that boxing was somehow the only thing that bridged the sectarian gap in Belfast. Somehow ritualized combat resulted in friendly relations. This is something I will be exploring on my next trip to Belfast in July.

Belfast, Northern Ireland

Paul McNally, 26 years later in Milltown Cemetery, West Belfast, Ireland.

Small Arms: Children of Conflict is also the name I have given to an exhibition of 36 black-&-white photographs from the '80s, which will appear at The Chazen Museum Art in Madison, Wis. I am also publishing a book by the same name of the photographs. The artistic royalties as well as print sales will be donated to UNHCR (The United Nations High Commissioner on Refugees). While working in Lebanon, Pakistan and Afghanistan this organization was tremendously helpful to those enduring conflict as well as to myself and I would like to thank them with this support and as a way to help those directly affected by political conflict.

© Michael Kienitz

|

|

Back to July 2007 Contents

|

|