|

Update:

Still A Secret War Part II August 2007

|

|

In late December 2006 I flew to Fresno, Calif., to witness Hmong New Year celebrations and meet a CIA legend – Hmong General Vang Pao. I was nervous and excited. Vang Pao has a reputation that is as gray as the fog of war. His detractors say he is a con man and a killer. Many who fought with him say he was fearless against insurmountable odds defending his homeland, always loyal to the U.S., and perhaps the greatest guerilla leader of the 20th century. For many Hmong he remains god-like.

I first met Vang Pao when his motorcade of five vans loaded with an entourage of 20 to 30 of his advisors and bodyguards arrived at a small restaurant in Fresno. When Vang Pao emerged, I found he was with his former mentor – an even bigger CIA legend – Bill Lair, who recruited Vang Pao for the CIA in 1961 and masterminded the initial phases of the "Secret War" in Laos.

Fresno, Calif. – Retired CIA agent Bill Lair (right) with Retired General Vang Pao at Hmong New Year celebrations, Fresno, Calif., Dec. 29, 2006. Bill Lair was the agent who recruited Vang Pao and the Hmong for the CIA in 1961. At the left is Vang Pao's alleged co-conspirator, Harrison Jack. On June 4, 2007, Vang Pao, Harrison Jack and nine co-conspirators were charged in U.S. Federal Court with plotting to overthrow the government of Laos. The men were caught in an FBI sting operation called "Tarnished Eagle" for allegedly trying to purchase weapons, including AK-47s, Stinger missiles, and other explosive weapons.

I am one of few journalists that have been to the remote mountains of Laos to document the plight of the desperate Hmong resistance and refugees still hiding in the jungles 30 years after the Vietnam conflict. Seeing Vang Pao and Bill Lair together caused me to flash back to that moment six months before when I was in the mountains of Laos.

On July 4, 2006, I gathered my camera gear and prepared to leave the jungle. The Hmong jungle people gathered around the bamboo hut constructed for my visit. Some cried, others smiled; they had high expectations. All their hopes for freedom and a normal life rested with me.

As an American many just assumed I must be CIA, or an agent from their former ally. It was really the only inference they could draw. Many had hidden here in the jungle since the U.S. pulled out of Laos at the end of the Vietnam conflict.

In 1961, when the first CIA agent, Bill Lair, arrived to recruit the Hmong, he came out of the sky in a helicopter. He picked a Hmong leader named Vang Pao to lead the Hmong in counterinsurgency. Their mission was to defend the Kingdom of Laos from a small band of invading communist insurgents and the massive North Vietnamese Army.

The Americans gave Vang Pao god-like powers via the U.S. military machine. If a remote village needed pigs – pigs would parachute from the sky. Guns and military hardware fell in abundance and soon the Hmong were scoring brilliant ambushes on communist insurgents. If Hmong villages were threatened, they called Vang Pao and aluminum supersonic birds swept in, demolishing their enemies. If the Hmong wanted money – it fell too.

It was all a bit much for mountain people with no education, most never having seen a car, but it fit perfectly with their animist beliefs. The Hmong had always prayed to the spirits in the sky, and Hmong lore was centered on a god that would one day descend from the sky and establish a Hmong Kingdom. For many Hmong it was clear – the prophecy had come.

I had come to document their plight, specifically an alleged massacre in which the Lao Army ambushed 26 Hmong who were looking for food in the forest. Only one adult male was killed; the others were all women and children. Five suffered injuries and five babies died in the days that followed because their dead mothers could not breast-feed them. Sadly this is nothing new. The communist Lao government has reportedly massacred thousands of Hmong since seizing power in 1975.

Laos – Bla Za Fang, 80 years old, holds his battered American-made AR-15 he used as part of the CIA Secret Army, hiding in the jungle near Vang Vieng, Laos, July 3, 2006. He fought for the French when they held Laos as a colony and later fought for the CIA working in demolition teams to sabotage the North Vietnamese Army invading Laos. On Oct. 10, 2006, 438 people from his group surrendered to Lao authorities - and vanished - despite promises by the Lao government that they would treat them well. He fled to Thailand as a UNHCR refugee and is currently in extreme danger of forced deportation by the Thai Military Junta.

Back in Fresno, I reached out to shake Vang Pao's hand, while these memories from the jungle raced through my mind.

Vang Pao greeted me graciously and granted me an audience for about 45 minutes. His English was much better than I expected. I learned he spoke seven languages, and at age 77, after having spent decades on the front lines of a brutal war, he still looked strong. And then we were off in his motorcade. It was Hmong New Year in Fresno and there were thousands of Hmong Americans dressed in traditional clothing celebrating their Laotian heritage. It was beautiful to see and provided a stark economic contrast to the living conditions of most Hmong in Laos today.

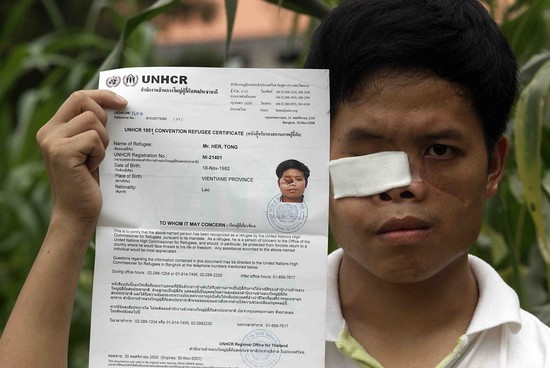

Thailand – A refugee, Tong Her, holding his UNHCR refugee certificate in Thailand. He escaped from the jungles of Laos after half his face was shot off by the communist Lao Army. On Jan. 30th, 2007, Thai authorities tried to forcibly deport Tong Her along with 152 other refugees. The deportation was postponed after the Hmong men barricaded their jail cell and threatened mass suicide if they were forcibly sent back to Laos where they face possible torture and death. The men reportedly declared, "We would rather die in Thailand than be sent back to Laos." (Deporting recognized refugees is an illegal act against a principle of international law called non-refoulment.) On Oct. 10, 2006, 438 people from Tong Her's group surrendered to Lao authorities - and vanished, despite promises by the Lao government that they would treat them well.

On June 4, 2007, Harrison Jack, Vang Pao and many Hmong I had met were arrested by U.S. government agents for plotting to overthrow the government of Laos.

Whether Vang Pao is guilty or not, this all must seem very strange to him. Hmong resistance groups have operated freely in the U.S. for more than 30 years, sometimes launching attacks in Laos with the full knowledge – some say encouragement – of the U.S. government (at least until the end of the Cold War).

During the Secret War, Vang Pao was given a VIP tour of the White House and many important leaders including congressmen visited him in Laos, making all kinds of promises. When the American public got tired of Vietnam many of those same important leaders lied, claiming they knew nothing about Laos or the secret war. The politicians thus deceived Americans to save their own jobs from the voters' discontent. This action led to the abandonment of the Hmong and the slaughter of thousands of Hmong by the communists who acted like war criminals. This is just one of several times in U.S. political history when we walked away, leaving populations vulnerable.

And this is what Vang Pao's attorneys will base their defense on. In 2006 alone up to 1,000 Hmong hiding in the jungles of Laos surrendered to Lao authorities due to Lao military pressure, an inability to defend themselves and lack of food or medicine. All of these Hmong have vanished and Washington has not held the communist Lao government accountable. And Thailand continues to forcibly deport Hmong asylum seekers, 160 of which immediately went missing in Laos on June 9, 2007, five days after Vang Pao's arrest. Vang Pao and many Hmong have for years been actively lobbying the American government for humanitarian intervention in Laos, so given some of the circumstances it is hard to fault him for his resolve.

Vang Pao may be guilty of a lot of things that don't make for pleasant conversation – then again, he may not be. It may be all part of his legend and myth. And whatever bad things he may have done, the U.S. government has known about it for a long time.

One thing most experts agree on is that Hmong American resistance groups have usually lied to and encouraged the Hmong in the jungles of Laos to stay and resist, promising help is on the way. Meanwhile, they raise funds in the name of the resistance (using Vang Pao's name, often without permission) but instead use the money for fancy homes and cars. But again, the U.S. government has known about this for a long time too.

As for the American government, it maintains a large well-funded staff searching for MIAs in Laos and in 2004 the two governments signed a free-trade agreement. And the U.S. has yet to give a proper accounting of the Agent Orange it dumped on Laos, presumably to protect Dow Chemical from more lawsuits. Yet to my knowledge, it has not a single staff member who is dedicated full-time to help resolve the Hmong issue in Laos.

The most criminal thing about this is not that Vang Pao is being charged but that so many others are not. What is the fate of the U.S. leaders who approved dropping 90 million cluster bombs and voluminous amounts of Agent Orange (experimental weapons) on Laos?

Thailand – Tense scenes at the Nong Khai Immigration Detention Center in Thailand, Jan. 30, 2007, as authorities tried to deport 152 Hmong refugees back to Laos. The deportation was postponed after the Hmong men barricaded their jail cell and threatened mass suicide if they were forcibly sent back to Laos where they face possible torture and death. The men reportedly declared, "We would rather die in Thailand than be sent back to Laos."

Like the Hmong in the jungles of Laos today, Vang Pao was born into a culture of war. He fought to save his homeland from the invading Vietnamese communists for almost three decades, longer than any American ever. When the Americans arrived they turned Vang Pao into a Hmong god and for a while he probably felt like one. However, approximately 35,000 Hmong were killed fighting with their allies, the Americans; this allowed the U.S. to avoid committing ground troops (body bags) to Laos. Many thousands more Hmong were massacred by the Lao and Vietnamese when American politicians abandoned them.

Many American servicemen returned from Vietnam after serving a two-year tour suffering from post-traumatic stress. When Vang Pao arrived in America, there was no VA or counselors to help with what he had seen. He had lost his country, been injured in action, fought on the front lines of dirty wars for 30 years and thousands of his comrades and relatives were dead. Since 1975 he has had to listen to reports coming out of Laos reporting the same kinds of tragedy for his people. He listens with a handful of old CIA friends who helped process thousands of refugees while the communists carried out their atrocities.

I don't know what Vang Pao thinks but you have to wonder what this experience would do to a man. How did all of this affect him? How would it affect you? If Vang Pao is guilty, what about the Lao government? Is this American justice? In the words of retired Brigadier General Hiene Alderholt, "Vang Pao's a son of a bitch, but he is our son of a bitch

© Roger Arnold

|

Back to August 2007 Contents

|

|