|

→ September 2007 Contents → Column

|

A Letter From New Orleans:

Cry "Oncle"! September 2007

|

|

|

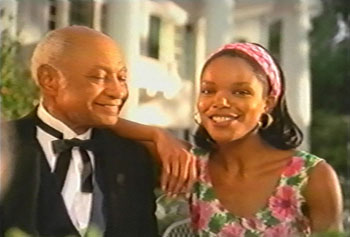

Uncle Ben approached his great nieces, a smile spreading broadly across his gentle mahogany face. The two handsome young girls stood waving in the hallway of his family's lavish plantation home. Jade, their mother, watched the old man's approach, knowing that Mon Oncle, as she had affectionately always called him, would once again come to her aid with his tantalizing sauces.

What had he in his bag? A jar of Creole sauce, or perhaps Louisianne, or a jar of Nouvelle Orleans? She knew that, with his help, she would feed her family and friends a grand meal, whatever he had brought.

Jade was right.

"Cut. Cut! I can see the bloody rain pooling on the dinnerware! Kill the lights. None of this sounds or looks like the Old South. This is not one bit New Orleans! None of it!," yelled the ascotted British director.

"The woman a bitch," he thought as Jade bumped him aside while hurrying to the heated room, but he refused to say a word out loud. All he had to do to get paid was keep his teeth in his mouth during the takes and smile broadly.

The American actor playing the part of The Nephew, however, was complaining loudly, as he had between every set-up for the last three days.

"I mean, what the hell we doin' here, man?" he screamed at the top of his voice. No reaction. The crew had long since learned that ignoring him was safest. Any recognition and he got louder. Still he persisted.

"This plantation nothin' but nigger hell -- the brothers didn't come here from the motherland wearing no cast-iron 'welcome home' bracelets -- they wasn't on no fuckin' VACATION, man. And then they get stuck here bein' FREE -- meanin' they no longer slaves, but now they got REAL slave wages and maybe a shack, and now they got to BUY they own food from the Man. So here we sit with this honkey muthahfuckah, and he got us actin' like we OWN the place? It's a sin, man. It's a fuckin' sin."

The Nephew quieted immediately. He needed the wages he was to receive in cash when the shoot wrapped. He walked into the craft services tent. Bottom line was there were side benefits to the gig. This bit about being able to eat all day was a definite perk.

In the sequestered side kitchen, Jade sat drinking Provençal wine with the advertising executives. The French agency had agreed with the UK production company that American wines would likely be unpalatable, so an extra catering expense had been approved as a budget line item. Consequently, they'd hired an experienced sommelier in Paris who'd assembled and transported several cases filled with a variety of admirable vintages on the plane from DeGaulle.

Jade, too, had been imported to play The Niece's part. She hated being so far from real civilization. Even those who spoke French here, like the First Assistant Director, were not understandable.

"Quelques-uns de ce patois Acadien soi-disant," she speculated to the casting director. The language she had been hearing was supposedly some of this Cajun patois.

The agency had, unfortunately, decided that Jade's own French voice was far too French, and didn't sound like it should for it to be considered by Parisians as Southern and American and antebellum. After all, this commercial would only air in Europe. The account executives were already auditioning females back at the hotel, looking for the proper accent. Something cruder was needed, they thought. Rougher. Something unrefined. Like America. Like New Orleans. Especially like New Orleans.

The food stylist had already dumped the last take's steaming entree into the overflowing waste can, with her assistant preparing to strategically stuff a fourth platter full of the product with dry ice. The ice was a perfect tool for giving the food the steaming, appetizing, just-off-the-stove look that made audiences salivate. She'd already soaked and dried another bowl of rice with glossy liquid glue so that it would both remain shiny white and stay in place as the sauce was ladled over it. "Savory" had been the director's sole descriptive instruction, and she knew how to deliver savory.

Dry ice and white glue.

Three makeup artists were back at work lightening the skin of each of the eight actors and actresses. The English director had decided that the actors and actresses he had chosen were, after all, too dark to be considered properly "Creole," and was determined to preserve his idea of authenticity. After all, hundreds of thousands of people would be persuaded to buy this product as nourishment for their families on the perceived truth of the advertisement.

As the American executive-in-charge-of-production, setting up all the monumental multi-cam 35mm film logistics in pre-production, I'd helped spend a substantial amount of the approximately US$4 million the 30-second commercial would finally cost after post-production polishing was completed. There were massive 30-foot cranes, dollies with straight and rounded tracks, electrical generators with hundreds of yards of cabling, gaff and grip trucks, and a hundred personnel to house and feed on location for the better part of a week.

I had taken the job willingly, fully knowing the ethics of the work. Never a rich man, but after many years at least modestly financially solvent, I had bought my first-ever house, a serious fixer-upper, and was in the midst of the overwhelming process of house restoration in New Orleans. I needed to maintain serious cash flow. There were more toilets to be bought, dozens of walls of new sheetrock to be installed, floated and sanded. Wiring and plumbing to be laid. Taxes and insurance to be paid.

I could not afford to hold out for Art. I needed immediate and ongoing Commerce.

Thus, in my own weak-willed way, did I help perpetuate another of modern civilization's illusions, and delusions, about the heart of my hometown.

On the other hand, the sauces were quite tasty.

© Jim Gabour

|

|

Back to September 2007 Contents

|

|

Later in the afternoon, a pianist played ragtime under the towering front veranda. The dutiful niece carried her steaming main dish between the stuccoed columns of the porch and out onto a linen-covered table set amidst the flourishing grass of her front yard, a huge space that sloped in the distance to the Mississippi River. Close to the house between the colonnades of ancient oaks, her hungry guests waited.

Later in the afternoon, a pianist played ragtime under the towering front veranda. The dutiful niece carried her steaming main dish between the stuccoed columns of the porch and out onto a linen-covered table set amidst the flourishing grass of her front yard, a huge space that sloped in the distance to the Mississippi River. Close to the house between the colonnades of ancient oaks, her hungry guests waited.

In her heart Jade thanked her Uncle for his idées recettes. His recipe ideas were always perfect for the occasion. Sensing her approval, the kindly man beamed in her direction, a familial affection apparent in his eyes. The rest of the family applauded. The pianist brought up another jaunty chorus of ragtime music. Happiness reigned.

In her heart Jade thanked her Uncle for his idées recettes. His recipe ideas were always perfect for the occasion. Sensing her approval, the kindly man beamed in her direction, a familial affection apparent in his eyes. The rest of the family applauded. The pianist brought up another jaunty chorus of ragtime music. Happiness reigned.

Massive 10K spots and multiple grids of nine-lights clicked and hummed as they switched off and faded into darkness. The actors and actresses, all English-speaking African-Americans except for the Parisian Niece, scurried to the warmth of the modern cafeteria kitchen, the soles of their shoes stained chartreuse by the dye used to make the Winter lawn look like Summer. Two stories of cleverly tinted blue-sky backdrop cloth fluttered on sandbagged 30-foot iron masts as the freezing January shower again pelted the set. One of the lesser lights exploded, sending a fine, stinging cloud of glass pellets over 84-year-old Freddie Washington, Uncle Ben for the last two ad campaigns, and the slowest-moving of the actors. A New Orleans native, he put his teeth in his pocket to protect them as he continued on toward the break room. They'd been loose all day, and he thought he was coming down with a cold.

Massive 10K spots and multiple grids of nine-lights clicked and hummed as they switched off and faded into darkness. The actors and actresses, all English-speaking African-Americans except for the Parisian Niece, scurried to the warmth of the modern cafeteria kitchen, the soles of their shoes stained chartreuse by the dye used to make the Winter lawn look like Summer. Two stories of cleverly tinted blue-sky backdrop cloth fluttered on sandbagged 30-foot iron masts as the freezing January shower again pelted the set. One of the lesser lights exploded, sending a fine, stinging cloud of glass pellets over 84-year-old Freddie Washington, Uncle Ben for the last two ad campaigns, and the slowest-moving of the actors. A New Orleans native, he put his teeth in his pocket to protect them as he continued on toward the break room. They'd been loose all day, and he thought he was coming down with a cold.

He didn't understand a word of the French that the woman from Paris had been saying in the commercial. She was intimidating to Freddie who, in his own neighborhood, was used to being deferred to with a certain gentility and respect, even among the meanest of company.

He didn't understand a word of the French that the woman from Paris had been saying in the commercial. She was intimidating to Freddie who, in his own neighborhood, was used to being deferred to with a certain gentility and respect, even among the meanest of company.

"A sin for which you get paid two hundred and twenty-five dollars a day," yelled the location producer from somewhere off-set. "Unless I finally get too tired of hearing this spiel. May I remind you that yours is currently listed as a non-speaking part?"

"A sin for which you get paid two hundred and twenty-five dollars a day," yelled the location producer from somewhere off-set. "Unless I finally get too tired of hearing this spiel. May I remind you that yours is currently listed as a non-speaking part?"