A

REPORTER’S

LIFE

GOOD NEWS, BAD NEWS

By

Eileen Douglas

Walking through the

Robert Capa exhibit now on the walls at New York’s International Center of Photography---in with the

famous photographs of the Spanish Civil War and the landing at

D-Day—you’ll find a typewritten letter he wrote from

China to a friend in New York in July 1938. Capa was in China working

as part of a film crew while the war to repel the invading Japanese

raged. When he had the chance he also shot his own black and white

stills of the fighting. He spent many months there, often waiting

around for the next big thing to happen. And, in the letter he

mused, regretfully.

“The war photographer’s most fervent wish is unemployment, slowly

I am feeling more and more like a hyena. Even if one knows the value of his work,

it gets on the nerves. Everyone suspects that you are a spy or that you want

to make money at the other’s man’s skin.”

I have never been a war photographer. And many years went by,

working in a newsroom, before it struck me. But, eventually,

yes. I did realize. Working

in news, in fact, even if one knows the value of his or her work, is more

often than not “making money at the other’s man’s

skin.”

What is a “good” story? A good story, it’s true, may be good

news. Who won the mayor’s race. The kid who fell down the well, rescued.

The destitute father of six who wins the lottery. A visit by the Pope. Good

news for those involved, certainly (unless that was you or your guy who lost

the mayor’s race.) But more than likely a “good story” is

10 people die in a smash up on the interstate. Even better is 20 people die

when their bus goes off a cliff into the river. And if a “good” story

is forest fires burn villages in Greece, then better yet is forest fires

ravishing upscale houses closer to home, say in California or Arizona.

A “great” story,

anyone who’s worked in a newsroom knows, is

a hurricane that kills a thousand and wrecks a city. A bomb that goes off in

midtown. The assassination of the president. In other words, a big story with

lots of punch and tons of angles. Now there’s really something to talk

about. Can’t you feel the adrenaline rush as first word comes trickling

into the newsroom and you gear up, grab your hat, and race out the door with

your camera, or, your script in hand for a bulletin, into the studio. Then

there’s

the glee of the “nailed it” feeling you get when the heartbreaking

audio or footage or copy pours in. And with a really “great” story,

lucky you, you get days, maybe weeks of follow-ups. |

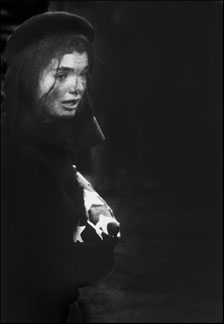

© Newsday

Photo

Jackie Kennedy at her husband's graveside |

|

It’s a conundrum

if you think about it--- although in the daily doing of the job

and the need to have “something good” to tell, you

can get lost and not think about it all---that what is good news

for the newsroom

is, sad to say, bad news for somebody else. Making money, as Capa put it, “at

the other man’s skin.” After all, what are you getting your

paycheck for? Telling the bad thing that happened to somebody else, more

times than

not.

Their misfortune is your good fortune. Now you’ve got a great lead.

In no way is this a criticism of journalists or journalism.

That’s just the reality of what we do. We describe life. Life is

full of good and bad.

Returning from the Capa exhibit, I found an email on my computer, asking,

in bold letters, “Why is there evil and suffering in the world?” When

I clicked, it was, what else, only another of those endless junk spams to get “quality

meds.” But there is evil and suffering in the world, just as there

is goodness, sweetness, victories, and heroic acts of compassion. In the

fullness

of describing life, you will describe both.

And there is another truth. Admit it. Bad news sells. Emotionally, the

journalist may get a buzz from our job because it is exciting to work a

big, dramatic

story. There is also a separation between “us”, the newsperson,

and “them,” the story’s subjects. The misfortune isn’t

happening to us. (Were it the journalist’s house burning down, he

or she would not think it such a great story. Rarely, however, is that

the case.)

But the journalist is not the only one. The reader/viewer/listener wants

to read about/hear about/watch disaster too. Bad news pulls eyeballs. Disaster

for the other guy is a reminder of disaster averted for the viewer/reader.

And, in the end, that is why a really bad day for some poor unfortunate

out there can be a really good day for those who make a living always needing

to find “something good” to tell.

Eileen Douglas

Eileen Douglas is

a broadcast journalist-turned-independent documentary filmmaker.

Former 1010 WINS New York anchor/reporter and correspondent

for ABC TV's "Lifetime Magazine," she is the author of "Rachel

and the Upside Down Heart," and co-producer of the films "My

Grandfather's House" and "Luboml: My Heart Remembers." She

can be reached at http://www.douglas-steinman.com/