© "Standard Operating Procedure"/Sony Pictures Classics

Movie poster for documentary film "Standard Operating Procedure."

Errol Morris' latest film, "Standard Operating Procedure," about the abuse of prisoners at the Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq, is at times brilliant, infuriating, tedious, at one hour and 57 minutes far too long, boring, with high-end graphics that are far too slick, looking as if they are from an expensive television commercial. The musical score by Danny Elfman is too loud, similar to a feature film and too demanding on the ear. It never lets up in its effort to carry the viewer through segment after segment as if being subtle was something that never crossed Morris' or Elfman's minds. The relentlessness of the music gave me a headache. The heavy, pulsating score was so obvious that it failed to convince me of a scene's meaning.

Many films ago, Morris developed the Interrotron, a device that separates him from the interview subject by a TV screen. The subject never looks directly at Morris, which is the way interviews usually take place in films. Each of the interviewees sits against a blue-gray mottled wall that looks as if a painter left for lunch and never returned. Usually in tight close-ups, and sometimes in a medium shot, though always head-on, each subject comes up in a different position on the screen in different takes. Rather than the editor using a cutaway or a dissolve or a quick cut between comments to eliminate the dreaded jump cut, Morris moves his people sideways across the screen. I am not sure why he does that, but it did not bother me when I watched the movie. I found it valuable that the subjects looked directly into the camera compared to many films where the interviewee looks to one side or another (a method used in many documentaries so opposing interviewees shot at different times can appear to answer each other as if they were carrying on a debate.) Looking directly into the camera is a plus. It creates intimacy. The subjects' faces have little shadowing on them. The lighting is flat. The faces have a harsh tone. It makes it difficult to watch them as we listen to what they have to say.

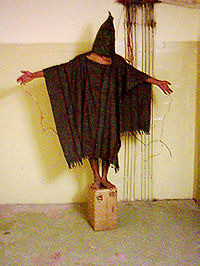

Abu Ghraib Prisoner Abuse

However, the Interrotron is another matter because it is a device Morris uses to manipulate the answers he seeks from his subject. It allows Morris to hide behind the barrier of a TV screen, never to confront his subject directly. In the film we occasionally hear Morris' voice asking a question. However, without eye contact, the interviewer seen only by the interviewee on a separate screen serves to create, at least for me, a false environment. Eye contact in an interview is essential to get at the truth. Unless we are dealing with a polemic, truth should not lie in the hands of the interviewer. Truth comes from the subject and how we, as an audience, parse what the subject says. It should always be up to the audience to decide if the interviewee is believable.

© Standard Operating Procedure"/Sony Pictures Classics

"Standard Operating Procedure" filmmaker Errol Morris.

Continuing a trend in many documentary films, Morris used re-enactments. Thankfully, they were few. They were not obtrusive, yet they were clearly not real. They are a trick played out on camera and in the editing to make the audience believe they were watching the real thing. I found them ungainly, and, more importantly, not needed. Let me take it a step further, or better, a step backwards and look at the various devices filmmakers use to make the audience believe that what it is watching is real. In some cases re-enactments are so bold that the director makes no effort to play a game with the viewer. We might see men on horseback. We might see people fleeing a volcanic eruption. However, there are other means to fool the viewer into believing what he or she is seeing is the truth. Some of these are: shots and sequences in soft focus; often fuzzy shots; sometimes shots in deep focus with a lens to approximate night; slow motion; slow motion that is out of focus; using sepia to designate an older time; re-enactments through close-ups of hands writing, or cars speeding down a road; exteriors of a place similar to but not the real location where an event happened; taking a shot from column A and adding it to column C even if each came from a different time and even a different shoot. This last is often used in films about war where it is mostly impossible to find the shot that defines the story you want to tell. Obviously, there are other examples. Filmmakers know them, use them and even create new ones when they think they need them. We are now in the world of fakery. TV news magazines have been using these gimmicks for years. In cable television there is hardly any real or true footage in what I define as hybrid documentaries. You know them when you see them, but you accept them because of their entertainment value.

This brings me to another point about so-called non-fiction films and the world of documentary filmmaking. Though wide and diverse, who among us who make documentary films has not strayed from time-honored methods in order to pander to current tastes? As we can well imagine, practices today are different from the past, recent or distant. Even techniques from the immediate past are meaningless and often discarded because filmmakers and critics consider them ancient, a dirty word. Some Internet junkies believe anything, even a few minutes old, is useless. Those who rely on the Web and its ever-changing dynamic demand speed, and speed fosters impatience. Cable television helped perpetuate the myth that it was making serious documentary films, but cable TV, with the occasional exception, only filled airtime. Despite that, standards remain high for independent films that play in theaters and for those few that appear on the pay channels such as HBO and Showtime. The cop-out is to call a film non-fiction. Using that handle allows the filmmaker to do whatever he or she wants to achieve his or her goal, however shaky it might be.

By now we should be aware of another controversy surrounding this film. Morris admits to having paid certain of his subjects to appear in his film, something not usually done in documentary filmmaking. Money should not change hands for an interview. If you give money to a person to talk about himself or herself or to discuss the designated subject for pay, you had better be sure that the person will not say what you want to hear, i.e., to satisfy you for that new pair of shoes he or she covets. Where does truth begin and the human desire to satisfy, perhaps even an individual's pandering cease? True, in documentary filmmaking, the filmmaker often buys the subject lunch, sometimes pays for his or her airfare, and even a hotel to stay for a night or two. These costs are for convenience. Providing those services are common and rarely cause problems similar to the ones I just described. None are as serious as paying the person to talk.

In a documentary, it is one thing to interview a subject until said person is ready to drop from exhaustion or runs out of information, though that is not technique of which I approve. As with a police interrogation, the subject may simply start saying anything to get some sleep, a cigarette, sip of water, or a sandwich. The interview becomes something other than filmmaking. It becomes manipulation. At times, though I detected this at work in "Standard Operating Procedure," I cannot say for sure it was in play.

© "Standard Operating Procedure"/Sony Pictures Classics

Brig. General Janis Karpinski, commander of the 800th Military Police Brigade at Abu Ghraib prison.

Errol Morris is no exception in his desire to make an entertaining non-fiction film. Though I find it difficult to find anything in "Standard Operating Procedure" entertaining. What he does in "Standard Operating Procedure" is no different from what some others do in documentary filmmaking. But even if what he does is unconventional, it does not guarantee or engender success. Good storytelling matters, and as much as I do not favor Morris' film, he knows how to tell a good story. Through no fault of his own, his story, thus his journalism – very important here – has noticeable holes. No officer, other than Brig. General Janis Karpinski, commander of the 800th Military Police Brigade at Abu Ghraib, appears in the film. Having been relieved of her command, she can say anything she wants, and, as her defense, she does.

For a documentary film to succeed it need not be based on journalism, but if the subject derives from a known news story, the journalism had better be strong, accurate and beyond reproach. Is the journalism in this film solid? To a point, perhaps, but it is incomplete. There are serious holes in the film because the government, meaning the Department of Defense, provided no one to speak about the tragedy of Abu Ghraib. Nor were the main perpetrators, currently serving long prison terms for the crimes at the prison, made available. The disclaimer stating these facts at the end of the film means we have a half-baked cake. Sadly, no officer was ever convicted of any of the crimes committed at the prison. Worse, no one in a high position, whether in the military or on the civilian side of the government, ever took responsibility for the events at Abu Ghraib. Of course, no one ever will. Perhaps that is the saddest message of all.

In America, there seems to be a naiveté among journalists, filmmakers and scholars about war and how it corrupts everything it touches. To believe otherwise is the highest expression of ignorance. The loss of morals in any society, or what passes for morality, will always be the victim. Abu Ghraib is not the end of the Western world as we know it. To a lesser extent, it is not even the end of the higher moral standards we in the United States supposedly have and aspire to. In Vietnam, were there other My Lais? Probably, but after all these years, they remain hidden from view. There were many atrocities in the Vietnam War, some reported, others not. In the Iraq war and in future wars, will there be other Abu Ghraibs or their like? Probably. Remember, it is impossible to escape that wars corrupt those who perpetuate them and those who fight in them. All the handwringing and all the investigations will change nothing. Note, too, in recent weeks there have been stories emanating from the prison at Guantanamo Bay about how FBI officials kept a dossier detailing how their brethren in the CIA tortured prisoners to get what its operatives considered important information. Meaning, as much as things change, they apparently never will.

© "Standard Operating Procedure"/Sony Pictures Classics

Lynndie England, one of the perpetrators of torture at Abu Ghraib prison.

Did I learn anything new about the disgrace of Abu Ghraib by watching this film? Not really. Did I see anything I did not see before Errol Morris made his film? Perhaps there were a few stills I did not see when the story first broke. The interviews, particularly of Lynndie England, and a few of the others are worth the price of admission. Observing the faces and hearing the words of some of those involved in the torture has enormous value. Reminding me that what happened at Abu Ghraib is a stain on America, however, does not convince me it was enough to make a film.

Ron Steinman, Executive Editor of The Digital Journalist, is an award-winning producer of television news and documentaries. He was NBC's bureau chief in Saigon during the Vietnam War. He is also an author and freelance documentarian through his company, Douglas/Steinman Productions. Buy Ron Steinman's book: Inside Television's First War.