I have a special place in my heart for photographers who occasionally get shot at, even though a Marine in Beirut once said to me, "You're crazy; you don't have to be here." Truth is, I never thought it was crazy to be one of the journalists covering one of the most important, sadly never-ending, stories of all time – wars – rather than photographing celebrity talking heads.

One of those journalists, Michael Kamber, has covered Iraq, Afghanistan, Liberia, the Sudan, Somalia, Haiti, Israel, etc. (http://www.kamberphoto.com/). He recently blogged his experiences with the digital Leica M8 rangefinder in Iraq at http://web.mac.com/kamberm.

It's important reading. The film Leica has been an important tool for photojournalists covering not only wars, but anything that demanded a small, quiet, unobtrusive camera, a viewfinder that let you see everything in focus, allowed you to see outside the actual frame of the photograph and anticipate pictures, could accurately focus high-speed normal and wide-angle lenses at their maximum aperture - and do it all in low light.

Now that much of photojournalism is digital, photojournalists are hungry for pertinent information on the digital Leica. Kamber points out on the first page of his blog that, while many of his experiences have been negative, many other photographers like the M8.

His comments have drawn both kudos and almost fanatical attacks on various Web sites and forums. In many forums you can judge where the comments are coming from because the photographers also post collections of their photographs. Let's put it this way, for the most part the most virulent of attacks come from photographers shooting a very long way from war zones and who, in some cases, seem to have more interest in their equipment than their subject. It's wonderful to take pictures of things that you find beautiful with equipment that does the job to near -perfection. But the carpenter and what he builds is more important than his tools.

I would also point out that photographing in Iraq as compared to most photojournalistic assignments is like driving in a demolition derby rather than a cross-country road race. You can use the same car for both, but it's going to get the crap kicked out of it in the demolition derby.

At one point in time, if you wanted a camera smaller than your Speed Graphic and your Rollei, you pretty much chose either a Leica or Zeiss Contax 35mm rangefinder. After awhile you could also choose a Canon or Nikon rangefinder. The Canon in some ways was similar to the Leica, and the Nikon had some features similar to the Contax. If you wanted to use macro lenses or long lenses, you used a reflex housing that attached a mirror box and pentaprism to your rangefinder camera. Existing all-reflex cameras, like the Exacta, did not have an instant return mirror or lenses that stopped down automatically. It was a little easier to travel with a rangefinder camera and convert it to an SLR with the same limitations.

In the early Sixties many of us bought a Pentax with an instant return mirror and a 50mm lens that stopped down to the taking aperture when you released the shutter. Of course, you had to cock the lens back open. But the SLR was on its way.

At first, you used the SLR with longer lenses. That's where the ground glass of the SLR provided an advantage in focusing accuracy. Microprisms and optical wedges didn't really equal the focusing accuracy of the long-base rangefinder with wide and normal lenses. But for many that became academic when Zeiss, Canon and Nikon stopped making rangefinders and news photographers started using zoom lenses. For those disgruntled few, autofocus came along and did much to improve the focusing of wide and normal lenses on an SLR.

Essentially, the remaining rangefinder, the Leica, became a specialty tool. It was small. It was quiet. The brightline viewfinder was effective in dim light. And, when properly adjusted, the rangefinder could focus a high-speed wide-angle or normal lens with amazing accuracy in the most godawful light. It became the quiet, discreet camera that could shoot in almost any light. (And no mirror bounce almost made up for the lack of image stabilization.)

There is no all-purpose, do-everything, single tool. A toolbox contains a screwdriver and a hammer. There is no Swiss Army knife with a power saw. No single camera is going to do everything best. The question is "Does the digital M8 compliment the DSLR the same way the film rangefinder cameras complimented the SLR?"

The rangefinder focusing and viewing is a wonderful compliment to the autofocus and "ground glass" viewing of the DSLR.

Autofocus sensors that guide the focusing of most lenses from slow zooms to high-aperture fixed focal lengths fail to take advantage of the large apertures of some lenses. My Canon 5Ds deal with this problem by having two sets of sensors. In addition to the "regular" sensors there is a set of central sensors that take full advantage of f/2.8 lenses. In theory, you could build in a special set of sensors for f/1.2 lenses, and you could build a Swiss Army knife with a buzz saw.

Accurate autofocus with high-speed wide-angles and normals varies with camera models and subject matter. Sometimes it can be dead on. But, for those who live and die by the wide open 35mm, f/1.4, the rangefinder is probably a wiser choice.

And no DSLR camera that steals a little of the viewfinder image to operate autofocus and TTL metering before sending the image to a "ground glass" is going to present as bright a viewfinder image in dim light situations as the window glass viewfinder of the rangefinder.

There are two points we should add about the M8's focusing and viewfinder.

A Leica lens has a rangefinder cam that positions a feeler arm in the camera body. When these are properly matched, focusing with high-speed lenses wide open is dead on accurate. Remember, everything has tolerances. It's possible to get a mismatch that won't affect most images but will be less than optimal when you're shooting up close with a very high-speed lens wide open. If you suspect your rangefinder focusing is not spot on, I absolutely suggest you send body and lenses to a really good technician to have them matched up. Some of the best are listed at http://www.lhsa.org/repair.html.

The brightline finder of the M8 is effective in dim light. But the frame lines for the various lenses are set to show the field of view at the close focusing distance of the lens. So, for most shooting, you'll see more in the final picture than the frame lines show in the viewfinder.

So, how does the digital M8 stack up as a compliment to the DSLR in other departments? It is small. It is not quiet. The shutter and cocking motor mechanism are noisy. So are motorized DSLRs. I had hoped for mechanical cocking à la a thumbwind. Perhaps it would be quieter; certainly when it happened would be under my control.

A word has to be said about image quality. It's exceptional. The frame is not full-size. In essence your 28mm becomes your 35, your 35 becomes your 50. You are using the central area of lenses with less need for extreme retrofocus designs. It may be easier to design a top quality wide-angle for a rangefinder than a DSLR.

And the sensor has a thinner cover glass. This means less correction for moire patterns and infrared than you probably find in your DSLR. But it does contribute significantly to a sharp image. (Much has been made of the infrared and moire problems in M8 reviews. I purchased the recommended infrared filters and stopped using them. So far, one image has given me moire problems that I took care of in Photoshop. These problems are non-starters for me.)

That said, we are talking about the high quality of the raw images. The JPG images from the M8 are not as good as the JPGs from my DSLR. If you are going to have to transmit JPGs and do not have time to produce those from the camera's raw file, you may want to leave your M8 in the gadget bag.

Kamber mentions that he is on his third M8. Me, too. As a consequence, I don't trust my M8, even though the third one has worked flawlessly for over a year. There will come a time when I will go out with only an M8, but, for now, the DSLRs are never far behind.

And, since we are on a negative note, let me say how sad I am that this digital rangefinder is so expensive that many young photojournalists will never get to play with the kind of camera that Cartier-Bresson, Gene Smith and a host of other heroes got to play with.

I sometimes shoot with a Canon G9 digital point-and-push. Instead of using the image screen on the back of the camera, I put Leica brightline viewfinders in the accessory shoe. That's right, the collected viewfinders cost as much as the camera. But I do wonder if a physically bigger point-and-push with a bigger sensor and a faster interchangeable lens à la the Digilux 3 with a Summilux-D 25mm, f/1.4 might eventually come our way and become to young journalists what the Leica was to their counterparts a half-century ago.

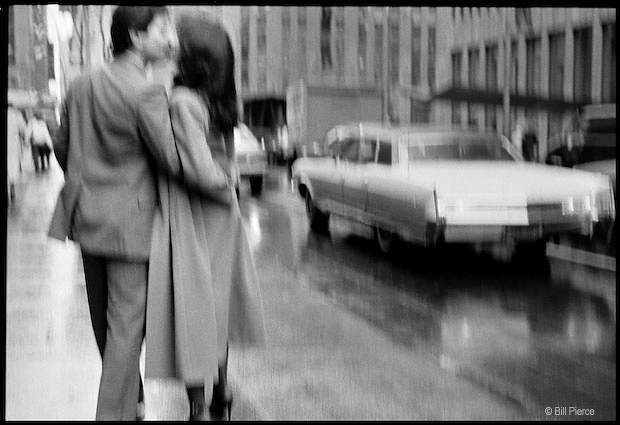

I thought this month's "picture that has nothing to do with the column" should have a certain anti-conflict quality. And, yes, it was taken with a Leica.