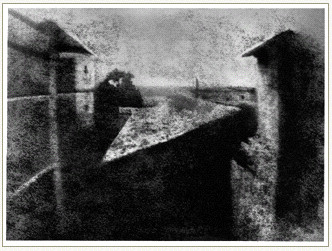

As visual journalists, photographers and filmmakers are concerned primarily with light. Technical image-making evolved from the revelation that light could somehow be captured and recorded in its variations by a device analogous to the light-gathering capacity of the human eye. Hence, in 1826, using a camera obscuro backed by a pewter plate coated in light-sensitive bitumen, Frenchman Joseph Niépce produced the first photograph. He called this new process "Heliography," which was initially rejected by the Royal Society of London. His first photograph of the rooftops of his country home in Saint Loup-de-Varennes is one of the most treasured artifacts in the archives of modern history. Niépce's discovery exploded into a revolution of capturing light that changed the world—a revolution that has yet to reach equilibrium.

The technology of light-gathering and image-making has transformed exponentially from Niépce's first success using light and chemicals to etch images onto metal, to today's sophisticated equipment that can literally see in the dark, revealing images that even the most nocturnally adept animal cannot sense.

Once upon a time, however, there was no technology, and we were just beings in nature with only natural, available light to determined our relationship to the world in which we lived. The original source of the Earth's light, the Sun, has not changed one iota since the dawn of humanity. The evolution of physical and emotional humankind into highly developed mental and spiritual beings has consistently been attended and determine by seasonal, repetitive cycles driven by the Sun.

Of the 12 months of the year, December is arguably the most introspective and spiritually oriented period of all. This inward focus and cyclical rebirth in the month known as December is a cross-cultural phenomenon found in primitive and modern religions as well as pagan traditions and ancient sun worshipers. The reason can be traced to mythology built around celestial phenomena and Earth's light/dark cycles.

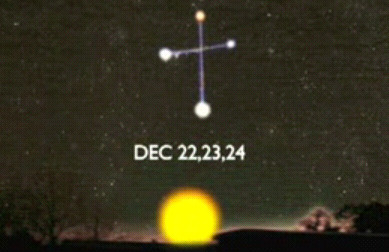

The darkest days of the entire year in the Northern Hemisphere are in the first three weeks of December. The sun enters the position known as the Solstice on the 21st, when it achieves its most Southerly position of the year in relation to the celestial equator. Following the Solstice in December (known in this hemisphere as the Winter Solstice), the sun seems to stand perfectly still in relation to the heavenly equator for three days, neither retreating further south nor beginning the northward movement that signals rebirth.

In June, another Solstice marks a reversal of direction and the cycle will continue, ultimately repeating in an endless loop of celestial movement, symbolically expressed as life, death, and rebirth.

In human experience, the darkness that envelopes us at the end of the year is echoed by many religious rituals and traditions as the final inward turn of the spirit and the rebirth of hope when available light then begins to increase and the cycle begins again. All this is coincidentally on the 25th day of December, and by New Year's Day, spirits are generally in full celebratory mode. Click on the images to view video tributes to the process that we celebrate by saying, "Happy New Year."

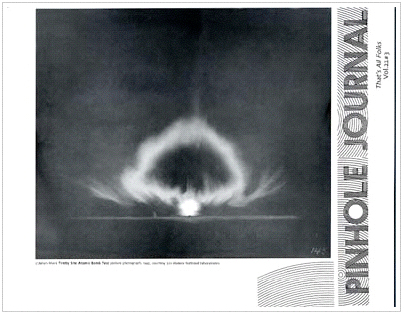

Available light was the only source used by image-makers for many years after the photographic revolution was in full swing. Photographers began experimenting with ways to artificially illuminate their subjects, ranging from creating explosions of fire to popping glass flashbulbs to today's high-tech equipment that bounces, enhances or electronically produces light. We're on the other side of the curve now from no-tech to high-tech to anybody's choice, and those who eschewed available light are now embracing it again because it is so much more easily captured. The un-enhanced light-gathering capacity of digital cameras is remarkable. Lest we of the digital revolution forget, in spite of the highly sophisticated devices now able to sense even the lowest lighting, there is one basic, fairly primitive method of making images which survives, even thrives today: pinhole photography.

Pinhole photographs are made with varying, often lengthy exposures through not an optical lens but a simple aperture the size of a pin, through which the light travels to the back of the pinhole camera, or camera obscuro, used to hold the film. The aperture requires nothing mechanical to open or shut, only time and patience to make the exposure. Because light is scattered equally from every point at the source, images produced from pinhole photography have a soft, ethereal quality, unlike some of our sharpest high-definition digital images at the other end of the photographic spectrum.

The community of pinhole photographers is sizable, comprised of individuals all over the world. Because of their characteristic, predominant devotion to the use of natural available light, I like to think of pinhole photographers as analogous to sun worshippers of ancient times. They are the pagans of photography.

Like some of the more primitive traditions that are being revived in contemporary times, pinhole photographs evoke a primal sense of the mysterious, the subliminal, and of a spirituality that I think reflects the power of the photograph at its best. Lines are blurred between what is in focus and what is not, so that a more diffuse but holistic picture can be perceived. In the pinhole photograph, the interplay between light and dark is expressed in a way that alters normal perception and apparent reality, and at the same time reveals the unconscious.

What we didn't see before when focusing on one part of the image is now uncovered, standing in equal value to the rest. In other words, we see not just the trees but we get an idea of the whole forest. Pinhole photographer and author Eric Renner, in one of his more notable photographs, saw his grandmother as the Moon. With a dream state evoked by light, and depth of field erased into equal value, subjectivity rises and wonder increases. At least, my wonder increases. I find pinhole photography enormously intoxicating—as do many others, judging from the worldwide interest it commands. Click on Renner's "Grandma Becomes the Moon" to see what I mean.

Write Renner and his partner, co-editor and spouse Nancy Spencer, at the Pinhole Resource to find out more about pinhole photography and the use of available light. Ask them how "Grandma Becomes the Moon" brought them together, a story that is as mystical and magical as the photograph.

As 2009 commences and we embrace a sense of renewal, let's hope we perceive, capture, and reproduce whatever light is available.

Beverly Spicer is a writer, photojournalist, and cartoonist, who faithfully chronicled The International Photo Congresses in Rockport, Maine, from 1987 to 1991. Her book, THE KA'BAH: RHYTHMS OF CULTURE, FAITH AND PHYSIOLOGY, was published in 2003 by University Press of America. She lives in Austin.