Like the fresh, exuberant display of a young bird in flight, fledgling Obama in his initial days as president reversed some of the more egregious policies of the Bush administration. He then made a sweeping gesture of promised transparency by releasing Justice Department memos that had been created to support his predecessor's policy of torture, euphemistically known as "enhanced interrogation." At the same time, he promised not to oppose the release of additional photographs that document even more evidence of abuse than has been revealed previously. For those following the issue, the existence of more images and videotapes was hardly a secret. Investigative journalist Seymour Hersh and members of Congress announced there were more following the emergence of the first images in 2004, that the initial images and videotapes were only the tip of a very big iceberg.

In the last few weeks, it has been impossible to ignore the firestorm of debate that ensued once it became clear how and for what reasons torture was conceived, condoned, and enacted. The blogosphere and even mainstream media exploded with legal opinion and commentary, outrage and indignation. Previously occluded revelations peeled away like the skin of an onion, and as the public rapidly connected dot after dot, the volume increased to a feverish pitch on the call for investigation and potential prosecution of the architects of torture that became official U.S. policy.

It is interesting that the president, who taught constitutional law for a decade at the University of Chicago, would concurrently reveal criminal activity and sweep it aside by suggesting the country simply accept the past and move forward. His suggestion, however, was quickly vetoed in the court of public opinion, and the president also found himself in the position of possible legal culpability in the future if he refuses to address alleged infractions of his predecessors. Thus, he left it to the Justice Department to pursue or not pursue accountability for the past.

In the face of a cacophony of criticism, what would Obama do about the some 2,000 additional photographs he promised to declassify—a promise he made when transparency seemed like a good idea? This issue is especially compelling to journalists in war zones who work tirelessly and at great risk to document conflict.

In an unexpected about-face, Obama reneged on his pledge to release the additional images of detainee abuse, a decision that further inflamed public outrage instead of palliating it. How ironic, since the reason given for holding the images was to avoid further inflammation of domestic criticism and anti-American sentiment, and most especially to avoid fueling more vehemence among those who would fight, detain, and possibly torture our own troops. Releasing the images would damage an already-deteriorating situation. Not releasing the images is deteriorating an already-damaged situation. It is a classic double bind.

The eruption of the entire issue seemed to take the president by surprise, as if he expected everyone to embrace his decision to simply close the door on the sordid past—a decision not really his to make. Constitutional lawyers emerged in droves to offer inspired and impassioned arguments in a concerted plea to preserve the integrity of our system. At this point, it became clear this is not just another political issue but the crux, maybe the lynchpin of our entire way of life. Should we leave a crack in the legal axel that could possibly sanction future abuse, the wheels could come off. Because of the influence we still have, as goes the U.S., so goes the world.

Do we condone now what we ourselves have punished as war crimes—that for which we have executed perpetrators in the past? And, do we become by default what we have philosophically and physically fought against ever since the inception of our constitutional government, regarded by sentient beings the world over as a government supported by one of the most enlightened documents ever written? Do we live by rule of law or by whim? Do we preserve checks and balances so that rule by whim or—in the very worst case – by insanity is impossible? Do we want accountability after a lapse, and if we do, when do we start? Do we save ourselves from ourselves and from our future selves, or not? And if we do not, what can we ever legitimately ask of the rest of the world? What, in turn, will the rest of the world eventually demand of us if we fail them and ourselves too? More importantly, when will we realize that the entire world is included in the concept of "we"; we are they and they, we. It seems the world is at a critical juncture, a watershed, and if there is a turning point, this seems to be it.

Canadian poet and songwriter Leonard Cohen wrote a song called "Everybody knows." "Everybody knows that the boat is leaking. Everybody knows that the captain lied. Everybody got this broken feeling. Like their father or their dog just died. Everybody knows the fight was fixed. The poor stay poor, the rich get rich. That's how it goes. Everybody knows." We know now that much has been done in our name that goes against the fabric of who we have believed ourselves to be. Collectively, as a nation that has served as a beacon of hope, are we, the rest of the world, and that hope, in jeopardy? There is more at risk than the soul of one nation. It is about the future of the soul of the entire world. Who are we, what have we become, and who are we going to be?

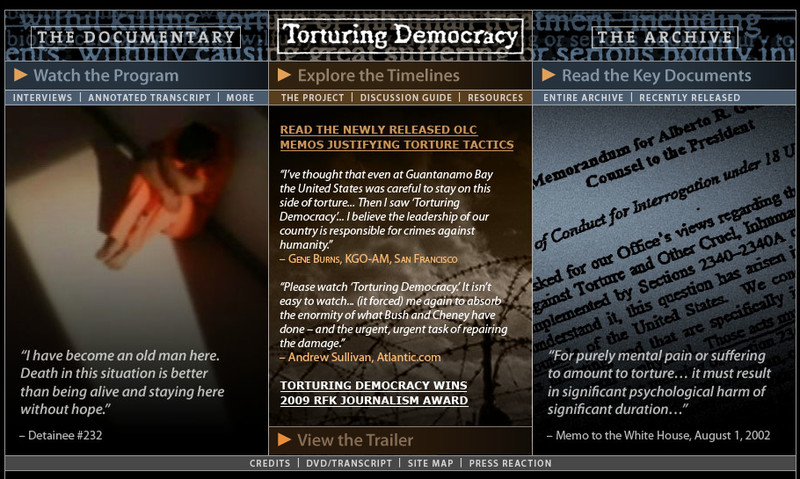

The short, award-winning documentary "Torturing Democracy" is online and can easily be viewed in one sitting. In a three-part video program, it outlines the dilemma facing us. The powerful documentary is supported by a trailer, documents, interviews, transcripts, timeline, press releases, discussion guide, and other resources. "Torturing Democracy" is a collaborative and joint project between the National Security Archive, Washington Media Associates, and producer Sherry Jones.

The issue of the still-classified images does not seem to be receding, in spite of attempts to justify their non-release. The demand to declassify and release persists not in small part because of the 2005 destruction of CIA videotapes of interrogation. Actions on investigation and possible prosecution of torture offenses being debated now will determine the course of events extending far into the future. Whatever happens with the images will have a direct effect on journalists doing documentary work in theaters of war, detention centers, or in any other unsavory spot on earth one might be able to imagine.

Most journalists pursue their careers because they are drawn to truth and have a passion to document and report it. It is somewhat ironic that the 2,000 classified photographs in question are not works by professional journalists, but were candid shots taken with hand-held cameras by persons present during the detainment and abuse of persons regarded as combatants.

Whether the photos and videotapes were produced professionally or not, they are evidentiary photography, which really is the true goal of photojournalism. The adage goes that the picture tells the story—of what happened, how and when it happened. In some cases an image can even reveal much, much more. In this case, the photos reveal details of the methods and extent of the abuses. If evidentiary photos are not allowed—if a tree falls in the forest and there is no one there to hear it—did it happen? Or will it have happened in a future devoid of witnesses or hard evidence? The answer could be a legal "no," and a policy of continued suppression of evidence could conceivably prevent anyone, ever again, being held accountable for abuse regardless of being on the scene or higher up in a future chain of command. With this kind of immunity, then, as the saying goes, the gates of hell open.

We have already seen the one-sided portrait of experience caused by forcing journalists to embed with the military rather than allowing them to work independently. It seems our entire mainstream media has become a sort of embedded entity inside a larger controlling one, analogous to journalists embedded within a combat operation. The result is an edited, controlled, manipulated, distorted, and sanitized picture of reality, such as we received during the pretty fireworks of "Shock and Awe," where instead of seeing human beings reduced to mangled and bloody corpses, we saw bombs bursting in air like some super-thrilling 4th of July celebration, complete with sophisticated soundtrack of appropriate war music. The general public, so used to watching movies, didn't—perhaps still may not—realize what was missing from the sterile portrait offered up as documentary footage and photos.

There are multiple woes facing nothing less than the whole of civilization at the moment, but I believe the issue of torture and accountability could fairly be called the number one most important spiritual issue now facing humanity. The issue at stake is whether humans remain humane or not. If we do not proceed into the future with our collective soul basically intact, then in a fundamental way we negate human progress made since the end of the Dark Ages.

Should we sanction war crimes and crimes against humanity anywhere on earth, then by default we fail, and perhaps fall, together. If we cannot hold at least this light for ourselves and for the rest of the world, and if we survive but have lost our souls, then we become another species, like the fictional walking dead. What is to keep us from repeating the past if we only say it won't be so? Do we stuff it all down a memory hole and tack down a cover? It is not just the few who are privy to classified information who are the only ones who know the terrible dark secrets. Everybody already knows.

If the argument for releasing the photos is countered by valid security concerns, then I favor releasing the photos eyes-only to the courts for investigation. The images do not need to be broadcast to the entire world like the no-pun-intended oversaturated scenes of waterboarding that run a hundred times a day on every news channel. What does need to be broadcast, however, is an authentic message that our taxi to the dark side will be addressed in a legal way that results in reestablishing the rule of law and forecloses on the possibility that it can ever happen again. It's not enough just to say let's move on and that we're not going to repeat it. It needs to be a decision backed by a guarantee, that guarantee being adherence to the rule of law. Without such protection, how will the world ever trust us? This issue is critical for the future, and the choice will be made now. Everybody knows, as Cohen croons in his dark and prescient melodies, that it's now or never. Everybody knows.

Beverly Spicer is a writer, photojournalist, and cartoonist, who faithfully chronicled The International Photo Congresses in Rockport, Maine, from 1987 to 1991. Her book, THE KA'BAH: RHYTHMS OF CULTURE, FAITH AND PHYSIOLOGY, was published in 2003 by University Press of America. She lives in Austin.