One of the greatest ironies of the last photographic decade, and there are any number of them, has to do with the treatment of some great cameras. Anyone under 25 probably has no idea what the hell I'm talking about. But if you began taking photographs when film was the medium of choice, you will recognize and remember that fleeting moment, at the beginning of the new century, when things got extremely unfair.

In 1925 a German engineer named Oscar Barnack created the first mass-produced camera to use 35mm film. His Leica soon became the standard which set the mark of what a portable, easy-to-use camera system ought to be (a system that included a variety of lenses, light meters and viewfinders, as well as the body.) I have, sitting on a shelf at home, a Model II (ca. 1933) black enamel Leica which my aunt gave me in 1964, once I had decided that I would become a photographer. She had picked it up in Germany on a touring trip in the mid-1930s, and it sat in her closet for about 25 years before I got it. Now, it has sat on my shelf for another 40. I used that camera early on, for several years, as an extra body to my otherwise sole and often lonely Pentax SLR. It was tiny, always worked as advertised, and if you could actually master loading the film (they were finicky) you could make some very fine pictures. Assuming you had some idea of HOW to make pictures. It remains for me the elemental baseline picture-taking experience. This is the kind of camera used by Capa and Cartier-Bresson in the '30s. And, simply put, if you could make pictures with an old knob-wind, screw-mount Leica, in the manner of the Masters, then you'd probably be OK with a more modern Nikon or Canon reflex camera. On the old Leicas, nothing was automatic. You had to use the rangefinder to align two images so that the lens was focused on the subject. The small viewfinder window was made for a 50mm lens and was a challenge to compose in. Advancing the film with a knob winder, while many times quicker than any of the then more popular medium-format roll-film cameras, was still slow. You could, however, shoot sequences if you were adept enough. And in the end, one of the great joys of "analog" shooting was that after a bit of lab work, it yielded a piece of film. Film. Something you could hold in your hand. Something that would keep, that would neither fade, nor create a blue-screen Fatal Error on a monitor. In fact, if you took a little care with that film, it would last longer than just about any hard drive that has yet been invented. And it will last longer than you.

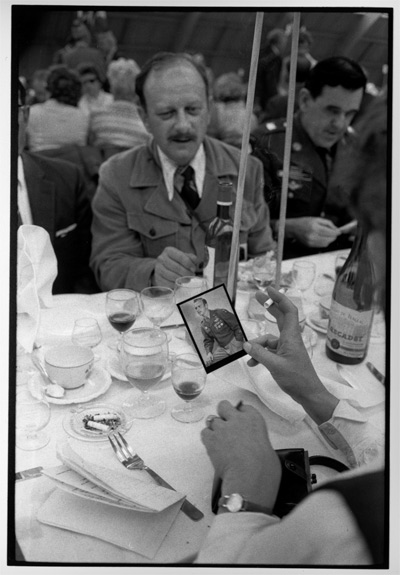

© 2009 (from 1974) David Burnett/Contact Press Images

D-Day Lunch Near Omaha Beach, hosted by the French for U.S. Veterans.

So it was just about a decade ago that this very unfair thing happened: digital cameras. The earliest of the so-called professional cameras were bulky and heavy, slow to operate (several seconds to power up for that 'second' frame), and had, by today's point-and-shoot standards, a miniscule 1- or 2-megapixel chip (smaller than many of today's cell phone cameras.) The sole advantage of the new cameras was speed of turnaround. Newspapers and wire services couldn't get them fast enough. The idea of skipping the whole wet darkroom process was vastly appealing, no matter that the bulky/slow/coarse cameras were a far cry in terms of quality from their film cousins. Speed was becoming the major criteria for deciding what was worth using. It did, of course, enable people at the far-flung corners of the world to send pictures almost immediately, though in doing so it created some hilarious moments. During the Bill Bradley for President campaign in 2000, I remember one great moment in Iowa, in the company of Charles Arbogast of The Associated Press, who had made a picture at the previous stop, as we raced into a small town hall, following the candidate, running through the lobby yelling, "Does anyone have a fax line I can use?" Files were small, and wifi was still a pipe dream. Dial-up, that relatively short-lived concept of using telephone lines, was still the modus operandi. He found a line, plugged it into his laptop, dialed the AP server, and started sending the picture, before joining the rest of us down the hall for that particular photo op. It was a case of the work reaching beyond the infrastructure. But it did get the image out, and those of us (me, for example) shooting Kodachrome and Tri-X still wouldn't know for three or four days if we'd actually made a picture.

The irony remains that the film cameras introduced at that time – the Nikon F4 and F5, the Canon EOS 3 and EOS 1v – remain the pinnacle of speed, focusing, design, and general usability in the world of film cameras. Had we had those cameras a decade earlier, our heads would have spun with glee at the sense of advancement they exhibited. To have an idea of how spoiled we have all become (8 gig chips, and cameras that can shoot dozens of images without stopping), just play a game: Next time you're on a job with your Mark II or D3X, shoot 36 pictures, and then take an obligatory one minute rest. Then shoot another 36. You get the idea. At a time when 36 images seemed to be more than a handful, enough that in most cases you could always "get the picture," the thought of shooting hundreds of pictures without stopping must have seemed like pure extravagance. (In 1979, at the signing of the Camp David Peace Accords, I was the "pool" agency photographer, and having shot like crazy as Carter, Begin and Sadat signed the agreement, I was out of film in 5 cameras when they stood to embrace. Ever since, I have tried to never run completely out of film or 'card' while there was still a chance of a picture. That afternoon, 5 times 36 didn't seem like such a big number.)

There does seem to be a resurgence in film cameras in medium and large format, with photographers looking for some other kind of completion or satisfaction that goes beyond the immediacy of that brilliant little screen on the back. Scanned film does have a different 'look' than pure digi sensors. Sure, "in Photoshop" you can do just about anything in post, and it has saved my butt more times than I can count. But just knowing that you don't know, that mystery which film inherently carried with it, the fact that you had to wait until that envelope from the lab brought back your precious originals, that did create a different kind of gut reaction in your work. I think it might have made your average photographer a little sharper, a little more wary. There was no fixing it later; you had to nail it in camera. Maybe it's a sense of purity which I miss, but I know that when I look at my pictures shot on film, I rest contented in knowing that those films are living happily, albeit in confined quarters, in row after row of file cabinets and that, barring an earthquake or fire, they will be there for me. I keep hearing the arguments about DVD longevity, hard drive longevity, server backups, and network storage. It's all well and good. But when I look at a picture taken, for example, at the 30th anniversary of D-Day (June 6, 1974) I know that those films have already lived longer than almost any hard drive ever constructed. Like everyone else, I have a certain faith in the fact that all the proper lights will turn on each morning when I flip my hard drives and Mac on. But someday that won't happen. Hard drives, like cars or airplanes or Waring blenders, eventually wear out. I hope it doesn't happen tomorrow or next week, or even by Halloween. But now and then I wander down into the basement into that dark corner closet where the film cameras are kept, and pop in a battery long enough to see those LCD screens light up, and shoot a few frames, just to know that I can. The older I get, the more the concept of permanence starts to drift away. And it gives me the best feeling to know that they're ready to take a roll of 36 and run it through its paces.

We're just sayin' ….

David Burnett is a renowned, award-winning photojournalist and author. Co-founder of the Contact Press Images photo agency, David was named one of the "100 Most Important People in Photography" by American Photo magazine. His book, "Soul Rebel: An Intimate Portrait of Bob Marley" (Insight Editions) was published in spring 2009. His latest book, a photo study of the Iranian Revolution, "44 Days: Iran and the Remaking of the World" (NG/Focal Point), will be published in September 2009.