June 2009 was a big month. Two vastly different but related events captured my attention. The first was the annual LOOK3 Festival of the Photograph held in Charlottesville, Va., June 11-13, a powerful and sophisticated celebration of photographic images from around the world. The second was the cascade of unfolding events following the Iranian elections on June 12. Fateful days these were, in June.

LOOK3 has emerged indisputably as a world-class event of increasing importance to the international photographic community and lovers of photography. The festival is held for three days in Charlottesville on the downtown pedestrian mall filled with shops, galleries, restaurants, theaters and gathering spaces. LOOK3, in its third year, has now fully come of age as an educational symposium and exhibition of work of the finest visual journalists in the world.

Sylvia Plachy, Martin Parr, and Gilles Peress were featured at this year's festival. In addition to in-depth interviews with guest artists, a host of other visual storytellers gave workshops, presentations and showed their work in hanging exhibits and night projections. The subject, as always, is the human condition, which includes not only human beings and world events but also everything else on the earth and under the sky.

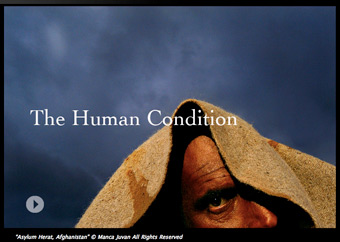

"The Human Condition" is a photo essay curated by Andy Levin, founder and editorial director of the photographic magazine "100 Eyes." The slideshow displays work from members of the Lightstalkers Virtual Community and debuted at the first LOOK3 Festival. Click on the image to begin this moving essay.

Most of us attending LOOK3 were barely aware of concurrent events happening half a world away that would bring something new to the human condition. While we were absorbing the world through photographs and digital imagery in Charlottesville, Iranians cast their votes in the June 12 presidential election. Shortly thereafter the outcome was contested and all hell broke loose not only in Iran but also in cyberspace.

Protestors poured onto the streets of Tehran as did security forces to control them. Violence erupted and demonstrators were arrested, injured, and some, killed. As officials attempted to control the information communicated by journalists, protestors resorted to the Internet and social media like Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube to upload eyewitness accounts, video, and whatever information could be disseminated via cyberspace.

For several years the world has witnessed a growing demonstration of the power of digital/cyber technologies used by citizen journalists. Think of the instant communications during crises in Madrid, Burma, and Mumbai. But in Iran it was different, because events were not just recorded but were affected on the spot by a feedback loop made possible by cyber technology. There seemed to be a leap forward, perhaps a paradigm shift, and something exponential and unpredictable happened. As the stream of information increased and the world responded, it seemed demonstrations were not isolated to Tehran streets but became an international, rapidly unfolding participatory event. Nobody could guess what was going to happen.

Boundaries separating professional journalism from unverified citizen journalism have become increasingly permeable. This time, however, boundaries were erased. As the regime attempted to black out information, international journalists were ordered to stay away from the protests altogether. News offices in Tehran were raided and locked down; journalists were harassed or robbed of their equipment; some were rounded up, jailed, and even deported from Iran.

In response, international media began to depend on the prolific flow of unverifiable reports emitting from demonstrators. Twitter and YouTube became primary news sources, caveats and disclaimers notwithstanding. Blogs covering tweets and images sprang up everywhere to manage the information.

Attempts to cut off the flow of information caused the BBC to declare the Iranian regime was waging "electronic warfare."

As predicted by Kevin Kelly in "Out of Control," every time a measure was taken to shut down a conduit of information, protestors found a way to counter the clampdown: by phone, by satellite Internet connection, by various modes to transmit e-mail, even by word of mouth.

Iranian officials moved to shut down the barrage of spontaneous twittering, but the U.S. State Department worked with Twitter to expand access to its Web site in Iran. Iranian officials placed filters and lowered bandwidths to stunt the flow, and yet, satellite access was independent, and those with information still found a way to share it. Twitter hashtag sites #iranelection, #iran, #Tehran, dominated the Internet and are still being analyzed. Tweets continue to pour in even today like rockets over a fence.

A YouTube video capturing the death of a young woman named Neda Agha-Soltan instantly elevated her to an icon. Her name, Neda, became the symbol of the new so-called Green Revolution against the theocracy that has endured for 30 years in Iran. Instantly transmitted imagery and tweets about an icon whose death was only minutes before perhaps defined this as a cyberwar, and the world was with the passionate young revolutionaries.

The raw footage of Neda's death and hours of protest can be easily found on YouTube, but I was particularly struck by the content of two video compilations, shown below, both of which speak of the social consequences of world events tied together by social media and citizen journalism.

In the first, a young American says before he saw the clip of Neda, he didn't really care what was happening in Iran because it didn't affect him. And yet, he was transformed by viewing the video of Neda's death. He says he came to understand that instead of what to him had been just a movie, "these are normal, average human beings … no different" from him except "they don't speak the same language." "Those people in Iran," he exclaims, "are fighting for their actual freedom and they're willing to die for it." His commentary is remarkable considering his self-described apathy toward the entire culture was reversed in a heartbeat by viewing one shocking clip.

The second clip by an Iranian source contains images from the demonstrations backed by stirring revolution-appropriate music, a very different kind of commentary from the preceding account.

Twitter and YouTube not only wrote much of the story, but became the story. We witnessed the power of something as seemingly insignificant as short sentences 140 characters long and cell phone video to coalesce a movement, mount a surge of effective dissent, and change events as instant communication engaged the sympathy of the world. It was hard to know what was information and what was disinformation, but it didn't matter except in the final analysis, which is far from done.

As days passed the entire world got into the act. Many people were instructed by news anchors and bloggers to change their Twitter account addresses to Tehran. Why, we might ask, but the point was to confuse the originating ID of information so that cyber censors could not effectively disable legitimate ones. It was odd to hear a television newscaster instructing people following Twitter from their homes elsewhere in the world to participate in a revolution in Iran. To my knowledge, that is a first.

In the U.S., ecstatic newscasters began to declare victory for the contesting candidate former Prime Minister Mir Hossein Mousavi and several commentators prematurely announced "the end of theocracy in Iran." Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamenei and President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad were finished, they said. Not so.

The demonstrations were reported by Al Jazeera English to be the "biggest unrest since the 1979 revolution." It seemed to be a true revolutionary uprising that would not quit. However, riot police and religious Basij militia contained and eventually quelled the demonstrations, but not until ordered by the regime to execute protestors, and not until almost two weeks after the election. The theocratic regime did not collapse as anticipated and pronounced.

Accusations of Western intervention began to fly, international journalists were missing or deported, UK embassy officials were arrested, Mousavi was accused of being a U.S. agent, and if all this wasn't enough, Twittering and citizen journalism that had appeared to be genuine became a confusing Neverland of information mixed with disinformation, where no one could tell authentic fact from fabricated fiction. In the end, it's hard to know just how effective social media and citizen journalism were after all. Much of the uprising carried on in cyberspace was neutralized by efforts to counter it.

In the U.S., the compelling news of Iran's revolution was suddenly displaced by disproportionate reporting of celebrity death and scandal on the home front. First, the story of the expected demise of icon Farrah Fawcett was swept aside by the sudden death of Michael Jackson, whose story was bigger than the death of Ronald Reagan and dominated the news for over a week. For those who became weary or disinterested in the bizarre story of Michael Jackson, the love affair of the governor of South Carolina filled in any remaining spaces and the Iranian drama disappeared from broadcast and print/online news almost altogether.

Analysts are still trying to get a handle on the effect, meaning, and significance of Twitter and citizen journalism on events in Iran. Once again, technology has changed the world, but in a way not easily dissected. We've known the day would come when instant feedback could change the story from moment to moment, and it seems to have arrived. Was it the "Twitter Revolution," or not? Wait and see, say the experts. It seems not unfair to ask, how can there be experts on epiphenomena we have never seen before?

In 1984 I thought the next big war would be fought primarily with symbolism. At that time, I could envision instant communication, but not today's technology. Even though blood is flowing in every corner of the Earth, I'm not willing to retract the idea. What we have now is the full amalgamation of passionate protest with technology, a mounting of counter techniques in response, an exponential relevance of instantaneous communication and feedback, and the spontaneous birth of iconic images.

Though it may seem unrelated, it is in fact an interesting time to review Michael Jackson's life. I have a sense that the 1985 video "We Are the World" by Jackson and friends was even more prescient and visionary than it seemed at the time. It's worth another watch while pondering recent events in Iran, which are not over yet.

So, the human condition in July 2009? We really are the world, and in our world, cyberwars have begun.

Beverly Spicer is a writer, photojournalist, and cartoonist, who faithfully chronicled The International Photo Congresses in Rockport, Maine, from 1987 to 1991. Her book, THE KA'BAH: RHYTHMS OF CULTURE, FAITH AND PHYSIOLOGY, was published in 2003 by University Press of America. She lives in Austin.