It would be hard for any observer of news to say they missed the Iran story last month. For the last two weeks of June, until MJ's untimely passing, little else was allowed to take place in the media besides the Iranian elections, post-election demonstrations, and the crackdowns that followed. This, in an age where every citizen (and pretty much most of the non-citizens) carries some kind of device for capturing a visual image. It could be a cell phone, a point-&-shoot camera, or a small video camera. They are ubiquitous, the one ever present feature at nearly any gathering of people in this modern age. (It really is about "being there"!)

2004 © David Burnett/Contact Press Images

An anti-Shah demonstrator fills his hands with the blood of a fallen martyr, the day before the return of Ayatollah Khomeini to Tehran, Iran, January 1979.

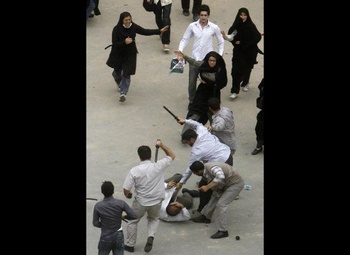

Personally, I abhor the term "capture" when referring to digital imagery (or any other kind of imagery for that matter). For me it conjures up images of itty bitty cowboys on itty bitty horses, swirling their itty bitty lassos while racing across a miniature landscape, hoping to 'capture' an image – in the form of a horse, of course. It is a very inelegant way of defining that stomach-churning, doubt-filled moment of photographic creation. Yet so many of the pictures and video we saw from the Iranian streets had their own kind of stomach churning, produced less by the wonder of a photographic image, and more by the imminent threat of violence and chaos. Much of it had an air of fresh reality, something that while technically flawed, was full of the moment. It was as if the rules of journalism had been suspended – a day we ought to have seen coming – and the only thing that mattered was the immediacy of those fugitive images, those that averted being blocked from transmission. The Iranian authorities tried to keep a lid on, and though we'll never quite know the degree to which they succeeded, the assumption now is that they are slowly going back through cell phone records and tracing those 'news' images back to their owners.

Yet even if they are somewhat successful in getting a handle on the flow for now, the genie really is out of the bottle. In technology, as in sport, a good offense will usually fall victim to great defense. And in this case, the 'defense' of the people in the street, though met with threats and intimidation, seems to have at least won the informational day, even if it didn't overturn the election results. As a more than casual observer of things happening on the street in Iran, I was struck by image after image that resonated on a very personal level. There was no shortage of irony in the events of the last few weeks.

Thirty years ago last Christmas, I stepped off a plane in Tehran en route home from a story I'd done in the Pakistan territory of Baluchistan. Next to the mountainous exoticism of the Baluch frontier, Tehran seemed like an almost quiet place. I'd known of the unrest there in recent days, and the large-scale shootings at a pro-Khomeini rally in September 1978, but I had no real idea as I rode from the airport into the city what lay ahead. Within hours I found myself in the middle of a series of big demonstrations, shots fired, positions taken, and I realized that this story was for real. The Revolution was definitely on.

I knew I would be around for a while, and quickly settled in to cover what in many ways would turn out to be one of the formative events of the end of the last century. The Iranian Revolution presaged much of what was to come in the Middle East, and the rise of Islamic fundamentalism as a potent force. At the time, however, one seldom knows just what import a story will carry. It remains for history to fill in the details, though sometimes that is much more quickly done than others.

As a photographer covering the Iranian Revolution, the problems I encountered were quite typical of the times. Just making those pictures, difficult as they were, was not the only challenge. This was still the pre-digital era (did someone say "analog capture?") and the hard part lay ahead: getting the films to a place (New York usually) where something could be done with them. I was shooting for Time, and soon after my arrival, my good pal Olivier Rebbot came to town for Newsweek. There were perhaps another half-dozen foreign photographers, including Catherine Leroy, the French woman who had worked in Vietnam, Beirut and other garden spots. Very quickly Olivier and I, in spite of the fact that we worked for competitive magazines, began sharing one of the most difficult events of our day: finding someone to carry our film out. The planes from Tehran to Paris and London left in the late morning, so we needed to leave the hotel about 6 a.m. to arrive at Mehrabad in time to make that critical choice. Much of civil authority had broken down, and at the airport there was no longer any guard keeping people out of the International Departures lounge. You simply entered the terminal, walked past the ticket counters, and slipped into the hallway leading you to the lounge. There, dozens, perhaps hundreds of desperate travelers waited, surrounded by their luggage in a scene right out of "Casablanca," for their flight to be called and their name to be acknowledged on the manifest.

In a move that would today have you arrested at most airports, Olivier and I would then start asking passengers if they would take our unprocessed film with them to Paris, say, where they would be met by someone from the

Time office who would pick up the film, thank them heartily, and ship it onwards to New York. You needed to find people who had some sense of responsibility and maturity. You didn't want them to have second thoughts, and maybe just toss your film packet into the trash. Or worse, turn it over to the cops as some kind of potential contraband. Olivier and I made a game of it, looking at the lines of travelers as we entered the lounge, and attempting to pick out a likely helper before even saying hello. Sometimes we'd bring a copy of a two-week-old magazine to be able to show them some of our previous work. We'd try and convince them of the import of the film getting to its destination, and how much we were personally relying on them. We always found someone, and only once, having made the mistake of trusting the packet to a radio correspondent, did the film go missing for a day. (He took it home to Tel Aviv and forgot to call anyone. Radio!)

I was, in the late '70s, in the throes of covering news and almost-news events in Kodachrome (that film which will cease to be at the end of this month.) It was not an easy choice: the film required an extra day or sometimes two to process at one of the very few worldwide labs that could handle it. Yet, the color quality, the richness and sharpness of the images made it worthwhile, and even the editors who sometimes groaned when being informed that KR was the film on the way, agreed that there was nothing else like it. So trying to make sense of a revolution, and do it in Kodachrome, was a kind of double challenge. Working the way we did required a certain faith in the rest of the system. There was that extra 'human' touch needed to find film couriers (let it be noted the Air France crews were always the most imaginative and cooperative) and yet you had to hope that along the way, all the pieces would fall into place, the film would make it to the lab, the images would be seen, edited, and engraved by dozens of people.

Watching the scratchy images coming from Tehran last month, I felt as though a trout might, having had the water drained from his pond. Everything had changed. The arrival of YouTube, Facebook and Twitter put to rest forever the need to rely on a pigeon to carry your film. The presence, already, of high-end digital cameras, Sat phones, and high-speed data networks has changed our environment completely. As one editor proclaimed a few years ago, "Every photographer in the world with a camera and a laptop is in competition with every other photographer with a camera and a laptop." Too true.

Now, as the tools shrink further and the means of delivery become more ubiquitous, that business we thought we were in … being magazine photographers … has morphed into a slightly less recognizable, but nonetheless demonstrable case of "image provider." And in a situation where the authorities (who were the people protesting the Shah and the U.S. in the streets 30 years ago) are trying to stifle reporting by professional journalists, reliance on the populace has emerged as the one last place for visual information. Now, quicker than a trip to the airport would have taken before, the pictures get uploaded and disseminated. Maybe it's a good thing that news photographs have become a commodity. Were we just living high on a concept that had no real meaning? Are all people with cameras equal? I guess a good case could be made that they are. Though there is definitely something to be said for a professional class of journalists, trained in the elemental understandings of what is both required and expected of a journalist. That line now seems to be fraying badly. Curiously, even as under siege as the Shah and his regime were at the time, never was the foreign press told to stay in their hotel rooms, under penalty of arrest, as has happened this year. The demonstrators from 1978 must have learned a lesson.

For years I always counseled young photographers that they needed to concentrate not on traveling to exotic locales simply to have a more eclectic portfolio, but to look close to home for that great story. My point was, save your money and find a story in the place you live. Within a mile of you there has to be a story every bit as good as something in Burma or Patagonia. Less exotic perhaps, but no less compelling. I felt that the real talent editors were looking for was that extra little sense of light, composition, and the 'moment,' the ability to bring an empathy with your subjects into the frame, those things which make a photograph memorable. I always felt that great images would rise to the top of the heap, and be noticed, and that those pictures, however mundane the subject might be, would let an editor know that someone had real talent. Now, as we flitter back and forth on Facebook and YouTube, trying to find the real "news" of the day, I wonder if that's true any longer. Speed and immediacy seem to trump art and vision. And I have to confess that while it seemed like a burden at the time, finding a willing soul to carry my film back to 'the world' was a lovely, almost poetic finish to the process. The reliance on one more human in that photographic chain was always a positive experience. I never walked out of that passenger lounge feeling anything other than satisfied, warmed by the exchange. Does hitting UPLOAD generate the same feeling? I'm not sure, but Mama, if you ARE going to take my Kodachrome away, I guess I'd better learn how. We're just sayin' …. David B.

David Burnett is a renowned, award-winning photojournalist and author. Co-founder of the Contact Press Images photo agency, David was named one of the "100 Most Important People in Photography" by American Photo magazine. His book, "Soul Rebel: An Intimate Portrait of Bob Marley" (Insight Editions) was published in spring 2009. His latest book, a 30th anniversary documentation of the Iranian Revolution, "44 Days: Iran and the Remaking of the World" (NG/Focal Point), will be published in September 2009.

Visit David's Web site: http://www.davidburnett.com/ and his 'blob' blog site: http://www.werejustsayin.blogspot.com/.