Big whoop. After several statistical triple back-flips, we now know that 96 percent of newspaper reading is done in the printed product. That's like talking about modern transportation by pointing out that 96 percent of buggy drivers use buggy whips. Hello? We switched to cars 100 years ago.

Writing on the Nieman Journalism Lab Web site, Martin Langveld made some valid statistical conclusions about newspaper readership. The problem is that he was asking the wrong questions. It isn't about newspapers; it's about news.

In case you haven't noticed, printed newspapers became irrelevant to the average person years ago. Ironically, they are still the biggest originators of news content. They just aren't directly benefiting from it.

And as they go, they are tearing at the core values of the news business. Staff reductions have nearly destroyed local news in many markets. Visible, but impotent newspapers drag down the credibility of all news sources in the public's mind. "I'm pretty sure we used to subscribe to it ...."

Content has been chopped, lightened and dumbed down repeatedly. Newspapers' primary strength, local coverage, has been replaced by syndicated content that is available everywhere.

Failing newspapers are the festering wounds of journalism. As they fail, their so-called "principles" are dropped faster than David Letterman can redefine sexual harassment. You want advertising cloaked as "advertorial?" Ads on the front page? No problem. Just give me the cash.

Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and former chairman of Dow Jones Peter Kann, writing in The Wall Street Journal, blames free online editions for the demise of their parent publications. "The print editions still have customers willing to pay for at least a discounted subscription," says Kann, "but there are fewer of the customers as free online editions peel them away from print. And so the publishers are left to juggle their twin products—the old one in inexorable decline and the new one in commercial denial—and pray the future may be somehow different."

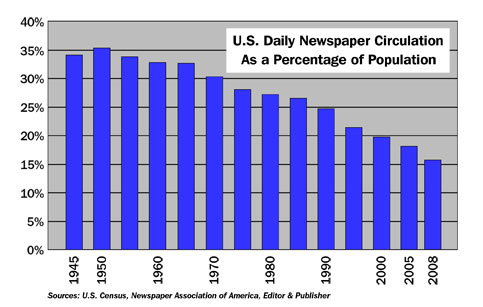

Certainly free editions contribute to print's decline, but that decline started more than a half-century ago. The Internet has merely accelerated that decline over the past decade. The current recession has put many newspapers into a terminal death spiral. Kann is right about the decline being inexorable. That makes it crucial to amputate the gangrenous print product to save the journalistic body.

Circulation and readership figures are ridiculous. Some "readers" recycle their paper without even removing the rubber band. Have you tried to cancel a subscription in the past few years? Sometimes you have to complain several times just to get them to stop delivering it.

With newspaper market penetration as low as it is, why on earth would we want to target newspaper readers as an attractive market? It's the people who DON'T read newspapers that we should be designing for.

Raw daily newspaper circulation in the U.S. peaked in the late-1970s. It has since fallen to levels not seen since the mid-1940s. But that doesn't nearly tell the story. Since the population has been growing all that time, market penetration has been falling ever since the end of World War II. This is not a cyclical "blip" that might rise again. The trend is irrecoverable and accelerating.

BAD THINGS CAN HAPPEN

At least one NHL team has responded to lack of coverage by papers in its area by hiring former journalists to create "coverage" of the team from within.

The Kaiser Family Foundation has hired two award-winning journalists to start a news service covering health care issues. As nice a group that the KFF might be, they still have an ax to grind in health care coverage.

GOOD THINGS CAN HAPPEN

A well-heeled sugar daddy has bankrolled what may be the largest such non-profit news operation in the country. The 28-person news staff of NPR affiliate KQED-FM and free labor from the UC Berkley Graduate School of Journalism will power the Bay Area News Project. Private equity mogul F. Warren Hellman is kicking in $5 million in seed money. The BANP will continue to seek grants from other benefactors to continue operations.

The San Francisco Chronicle is terrified. The online SF Appeal published an internal Chron memo referring to the pending launch. With the bravado of the terminally ill, Chronicle Metro Section Editor Audrey Cooper declared that the Chron would "smash whomever is naive enough to poke their noses in our market." Ironically, the Chronicle made an early and laudable foray into the online area with its SFGate Web site. But, like most other newspapers, the massively expensive print product is dragging it down.

TRUST THROUGH SOCIAL MEDIA

Like it or not, journalists now inhabit the nether regions along with politicians and used-car salesmen. The days when Walter Cronkite was the most trusted man in America ... well, Uncle Walter is dead.

Constant pandering to the lowest common denominator is the reason for journalism's plunge in public trust. In the pursuit of readers who already made it clear that they weren't interested, newspapers have alienated those who were interested in thoughtful detailed news coverage. Few want the vestigial dumbed-down product.

The road back to trust runs through transparency, inclusion and a return to old-school commitment to, as a media guru Dan Gillmor tweeted, "doing solid journalism, including stuff that challenges your world view." Journalists need to come out from behind the masthead and engage with readers. They need to let the public get to know them. When they do a story that runs counter to their professed views, their trust quotient will rise.

FUTURE

Imagine being able to virtually go to any spot on the Earth and see it in 3D, read comments about the sites, listen to local sounds, read menus from (and reviews about) the local restaurants. The views would be mixes of live and archival data, providing a near real-life experience.

Imagine a football game where thousands of people were simultaneously using networked personal video devices. You will be able to tap into those combined streams and, using real-time virtual reality stitching, zoom into any part of the stadium environment including sound and any available metadata.

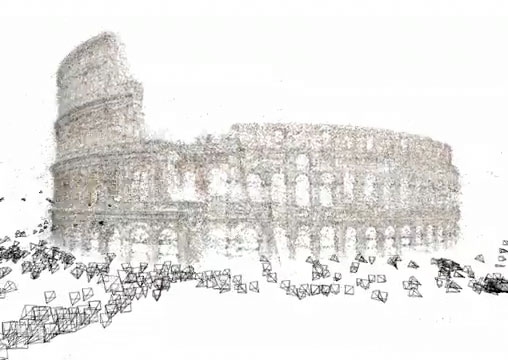

Applications for this imaginary world exist now. Google Earth has turned the planet into a customized fly-through theme park ride. A team of computer scientists at the University of Washington's Graphics and Imaging Laboratory using algorithms from Microsoft Photosynth created a virtual version of Rome from 150,000 Flickr images.

Surveillance cameras are becoming increasingly ubiquitous. It's hard to find a spot in London that isn't in camera range.

Covering a spot news event is going to become a matter of simply calling up the relevant data set from the cloud.

For the more conventional news experience, The New York Times is testing a custom news feed product. When you enter a search term, it suggests similar terms that already exist in the Times' system and returns stories from the Times' archives. I found it very fast and very easy to use.

All of the current publishing systems are transitional technologies. We know what we want, but the distribution and delivery systems haven't caught up with our vision yet. May they never do so.

GOING ALL IN

Newspapers are trapped between two worlds. They can't offer a viable online service because they can't spend enough on staffing. Meanwhile, they've lashed themselves to a sinking ship that they're bailing out by tossing journalists overboard. Of course, this drives readers away, causing the ship to sink faster.

The print product isn't just expensive, it is massively so. Writing in the Silicon Alley Insider, Nicholas Carson pointed out that for the cost of producing the print product, The New York Times could buy every one of its subscribers a Kindle. Make that two Kindles.

Publishers are terrified of throwing away the large print-based ad revenues. But they will also be axing their titanic printing costs. They could spend part of this saving on improving local coverage.

One of the biggest barriers to the success of online is the continued existence of the warm, comfortable print product. Fundamentally, most people resist change. Many continue to subscribe simply because that's what they are used to. Without the choice of the printed paper, readers who currently say that they prefer the traditional product would suddenly find out that the digital water is just fine and getting rapidly better.

Festering wounds need to be cleaned out so that healing can begin. Pandering to old-habit subscribers is choking off resources needed to improve the news product. The evangelizing necessary for an online operation to survive within a traditional newspaper siphons off energy and increases the likelihood of failure.

There is no guarantee of 1970s' profit margins with an all-digital product, but the print product is already on the national organ donor list.

Let's examine what is worth keeping about the newspaper culture and get rid of the rest of it. From there, we will be able to develop products that are relevant to people's lives rather than struggling to keep something when our customers have done everything short of getting a legal injunction to stop us from producing it.

Portions of this article were written in online discussions going back to 1995.

Mark Loundy is a visual journalist, writer and media consultant based in San Jose, California.