The first year of The Digital Journalist has been one of constant changes: experimentation, rejection of the unworkable, improvement, and expansion---a detonation of ideas founded by Dirck Halstead. As I read through the archives, I am reminded that this new site carries on a journalistic and visual tradition established long ago. It is this tradition I will speak to. I will only pick out a few exemplars from photojournalism, including photographers, equipment and processes that changed photography and journalism---bringing us to the digital image and its implications. [There are thousands of examples, and I would like to hear your choices if you would care to email me at this site.] Photographers' knowledge of their subject and craft, their access to that subject, and the speed and efficiency of particular distribution systems are the themes reiterated throughout. The intertwining of intelligence with new technologies is another way to express the pattern. The most inquisitive and erudite photographer in the first half of the 20th century was Erich Salomon. His work and his reputation are still rightly lauded. Period magazines and newspapers covered his short and finally tragic career with profound respect.

The British Journal of Photography (Vol. 82, No. 3922) reports on an exhibition of Salomon’s photographs at the Royal Photographic Society, in 1935, saying that "the new power placed in their [photographers’] hands by the unremitting efforts of manufacturers of camera, lens and film has given the opportunity of creating work which deserves a place among the most vital of historical records.” The editors observe that such “power must not, however, be abused, and it is to be hoped that such activities will remain confined very strictly to such as can be relied upon to exercise the utmost discretion.”

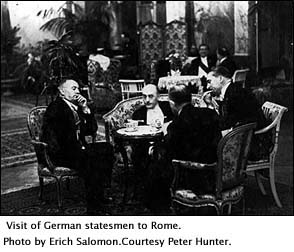

When he proposed making a portrait of a group of men indoors, he encountered the usual response, “They told me it just couldn’t be done.... That it was an unheard of thing; an absurd suggestion” (Photography, Sept., 1935). Hiding the camera became unnecessary on many occasions, at first because his statesman-sitters didn’t believe such a small object could be a camera, then later they realized that a published photograph by Salomon was a useful political tool. Aristide Briand, a former French Prime Minister, reportedly shouted at an important conference, “Where is Dr. Salomon? We can’t start.... What’s a meeting that isn’t photographed by Salomon? People won’t believe it’s important at all!” Much of his work was purchased by the House of Ullstein, which published famous newspapers and magazines. An art critic in the London Graphic coined the phrase "candid photography” in 1929 when writing of the photographer’s work. He was famous in his own time. Kurt Safransky wrote of the death of Dr. Salomon. He visited Salomon in Holland. Safransky said that everyone knew the Nazis were coming but Salomon “did not want to miss a single phase of the important coming events.... This time Erich Salomon came too close to the wheels of history...” (Popular Photography, Aug., 1948). Salomon died at Auschwitz. After the war, his surviving son, Peter Hunter, retrieved his father’s negatives. Some were buried in the chicken yard. Dr. Salomon changed picture journalism through the quality of his images, by seizing on a new format and technology and making it his own. He experimented and knew what he and his equipment could do--before flash bulbs and high speed film. He knew what was or would be news. He had access to large circulation periodicals which got the work out to literally millions of people. Most important of all, during the little over 15 years he worked, he went for content and waited for the right moment. His photographs were extraordinary; they were not only about technology but a superseding insight. As technology changes, photographic practices change and so does the expectation of an increasing speed of image delivery. In 1924, the first generations of the Leica camera, for example, used motion picture film for Leica’s own purposes. Now a photographer could carry a small camera with finely made interchangeable lenses and take 36 exposures! A big improvement over larger cameras using plate holders, each with two sheets of film. The photography it engendered---seen clearly in Salomon’s later work---changed European magazine photography. In the States, the Speed Graphic remained the reliable standard for another 2 to 3 decades. It too determined a type of photography forever associated with American photojournalism of the 1930s and '40s. The flashbulb, invented in Germany, was introduced to the American market in 1930 by General Electric. Photographers now controlled the light and carried it with them.

In most of the era’s work, the flash’s range determined the scope of the photograph. The artificial quality of the bright light source highlighted the subject, flattening and separating it from the rest of the scene, which became “background.” Considering the time it took to use individual film holders, and the necessity of arriving back at the pressroom with a usable picture for the front page, many subjects were posed. While this resulted in usable photographs and sometimes in wonderful images, it could also turn a local mayor into a wax figure straight out of a display at Madame Tussaud’s. As the choice of a camera helped determine a way to work and accessibility to different news organizations worldwide, another technology was coming into its own: the transmission of images over telephone wires. The Associated Press’ success at sending out the picture of a plane crash on January 1, 1935, to 24 of its members amounted to an about-face for an organization that had dealt solely in word journalism for over 85 years. The transmission of an early form of graphics, on the road to images, first grew out of experiments with interconnected synchronized clocks in Scotland in 1842. To this system, a stylus and other changes were made so that graphic transmission was possible. By the 1860s, a commercial venture in France connected Paris with several surrounding cities---for five years. Dr. Alfred Korn introduced photoelectric scanning from his studio in Munich. Though he had started earlier, his results appeared on the cover of the magazine, Scientific American in 1907. Another magazine reported that he had “discovered a new method for transmitting pictures by electricity. The process is a distinct advance on all previous inventions in this line, and bids fair to revolutionize the science of Journalism....” The writer realized that because Korn could reproduce black and white as well as shadings of tonality that “the new processis just as much an advance as is the modern half-tone block comparedwith the old line wood-engravings” (Photo Era). There were experiments and successes in many countries in Europe. In England, Robert McFarlane and Guy Bartholomew put together a system theycalled "Bartlane" in the 1920s. It utilized a punched tape, much like the old Wall Street ticker tape. The image was translated into variations of five-hole punches onto telegraphic tape and transmitted, reversing the process at the other end. Although it was an advance at the time, the resulting pictures looked like small, embroidered blackand white pieces of paper. The coming together of Morse code, halftone printing, and transmitted photographs meant that the ingredients of 20th century journalism were in place. Improved camera design and photographic emulsions led to moreversatile and individualistic ways of seeing. These photographs could, in turn, arrive at the newspaper with the text of a story. No moredeciding whether to go ahead and run the story first or wait for the images to be delivered by post. The tempo had definitely picked up.

At every stage of what we now call photojournalism, there has been searing individual images that remain imbedded in each generation’s memories. It is not, therefore, the technology that makes a great image but the skill of the photographer. Technology is used to produce anddistribute one person’s brilliant insight. In Eyes of Time: Photojournalism in

America there is a quote from the

writings of Umberto Eco, in "A Photograph," that is worth repeating

here. The “vicissitudes of our century have been summed up in a

few exemplary photographs that have proved epoch-making: the unrulycrowd

pouring into the square during the ‘ten days that shook the world’:

Robert Capa’s dying miliciano; the marines planting the flag onIwo Jima;

the Vietnamese prisoner being executed with a shot in thetemple; Che Guevara’s

tortured body on the plank in a barracks.

The only thing to add is the public’s expectation: if something is reported, we expect instantly to see the photograph or digitally captured still or moving image. It is incredible when an earthquake, forexample, takes place without photographs immediately available to describe it. Do we believe the story? Did it happen? Is it important? (Questions earlier asked or implied by Aristide Briand about having a conference without the presence of Erich Salomon and his camera.) Seamless “enhancements” made possible to large corporations with the advent, circa 1978, of Scitex, Crosfield, AP’s electronic darkroom, andnow through miniaturization, the introduction of computers into the home and onto the desktop which allow going from camera to page or cyberspacewithout a negative, have made the public suspicious of many photographs.(They should have been skeptical earlier, of course, when a newspaper turned out an edition utilizing the skills of large art departments wielding airbrushes.) Photojournalism, in all its forms, brings the past to the present in the form of historical document. Moment to moment the news ages. Meanwhile,digital equipment and cyberspace allow us to live within the future every second. In contemplating this moving target, I suggest, it is a good idea to think over some of the non-hierarchical postulates of “old” video. Notnecessarily corporate television of the 1950s and '60s, but the work of street-documentary videographers, guerrilla videographers, and the like. They took a new---suddenly portable---technology of the 1960s and brokethe “rules” of photography, television and film. They pushed to see things differently because now they could. They reached out to Buckminster Fuller and Marshal McLuhan for radical ideas about the presentation of information. This is the moment for the photojournalists, videographers, and editors to contemplate a new medium. Does the still-moving-video or digital image imply freedom from the past? What from the past is worth re-combining while creating a powerful news distribution system? The writings of Umberto Eco reinforce the power of the individual image. Hungarian and German editors brought us the picture story and LIFE magazine perfected the formula through the work of Eugene Smith and Larry Burrows. Surely the place of narrative, whether throughone picture or many, should not be lost. In the documentary PJ2001 about the future of photojournalism, produced by The Digital Journalist, many people from different parts of the news spectrum are interviewed. Ken Irby, of the Poynter Institute,identified one pitfall of the strict traditionalist: that person becomes a dinosaur because he or she is being prepared only “for a world that nolonger exists.” Arnold Drapkin, former picture editor of Time, also emphasized the necessity for growth of the photojournalist, to beready for a future far different than today. Robert Pledge, president of Contact Press Images, rightly said that if we really want the medium (and technology) to evolve in a certain way, we need to work to make ithappen. The Web, of course, is a distribution system par excellence. Anyone can get access to a worldwide unknown global audience. The Web's power is used by those with independent sites (remember the '60s videographers), and confirmed by established newspapers and magazines which have gone on-line to preserve and have access to a public whoseexpectations are shifting. If this is any kind of news to you, look at a good newspaper then go to washingtonpost.com, and then on to kurdistan.org (a site set up by Susan Meiselas). The world is waiting. Photojournalism is about thinking, feeling, about communication. It is a process that usually involves many people in a conversation that is newsitself. If we are free of the optical-chemical darkroom---free of the 19th century---we are not free of the obligation to see and share history as it happens. Marianne Fulton

Many Thanks to The George Eastman House and their curatorial and picture collection staff. |

In

November, 1931, Time magazine translated an article by Dr. Hans

Sahl on Salomon and his work from a German graphic arts magazine. Of a

"new photographic technic" Sahl writes: "It is the art of presenting the

psychologically important and interesting moment in a manner so striking

that the observer can comprehend the situation at a glance. The photo becomes

a camera anecdote....” He continues, writing that hundreds “of examples

could be drawn from Dr. Salomon’s practice, examples which would show just

how much cleverness and above all, how much presence of mind is necessary

in order to seize the right moment for taking a picture.”

In

November, 1931, Time magazine translated an article by Dr. Hans

Sahl on Salomon and his work from a German graphic arts magazine. Of a

"new photographic technic" Sahl writes: "It is the art of presenting the

psychologically important and interesting moment in a manner so striking

that the observer can comprehend the situation at a glance. The photo becomes

a camera anecdote....” He continues, writing that hundreds “of examples

could be drawn from Dr. Salomon’s practice, examples which would show just

how much cleverness and above all, how much presence of mind is necessary

in order to seize the right moment for taking a picture.”

Erich

Salomon held a German law degree, and had inherited family money. During

the inflation of the Weimar years, he lost his inheritance and began working,

eventually taking up photography for his advertising job at the age of

42. He used the new small Ermanox f.2 with glass plates, and then began

shooting with the Leica Model A, which used 35mm motion picture stock.

Each he hid in newspapers, boxes, and briefcases to gain unprecedented

access to his subject.

Erich

Salomon held a German law degree, and had inherited family money. During

the inflation of the Weimar years, he lost his inheritance and began working,

eventually taking up photography for his advertising job at the age of

42. He used the new small Ermanox f.2 with glass plates, and then began

shooting with the Leica Model A, which used 35mm motion picture stock.

Each he hid in newspapers, boxes, and briefcases to gain unprecedented

access to his subject.

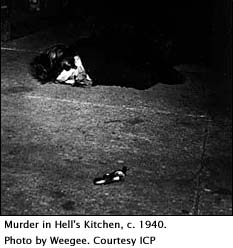

The

short throw of intense light---10 to 12 feet---resulted in pictures of

that era having strong stylistic similarities. Now, there is a tendency

to associate the work of thousands of photographers from that era with

that of Weegee, the best-known chronicler of crime. His photographs, often

taken at night of crime victims or gangsters, were only one approach to

the use of this equipment.

The

short throw of intense light---10 to 12 feet---resulted in pictures of

that era having strong stylistic similarities. Now, there is a tendency

to associate the work of thousands of photographers from that era with

that of Weegee, the best-known chronicler of crime. His photographs, often

taken at night of crime victims or gangsters, were only one approach to

the use of this equipment.

One

example from 1945: Joe Rosenthal handed off his Speed Graphic filmholders

during the fighting on Iwo Jima. One of those negatives was “OldGlory goes

up on Mt. Suribachi, Iwo Jima.” As the battle continued and three

of the marines pictured are killed, AP printed one of the most famous

photographs to come out of the war. It distributed to the news media

in 17 1/2 hours---an unheard of speed for pictures from the front.The widespread

appearance of this image, while the battle was still front

page news, amazed the viewer, and probably added an immediate boost

to its future as an icon.

One

example from 1945: Joe Rosenthal handed off his Speed Graphic filmholders

during the fighting on Iwo Jima. One of those negatives was “OldGlory goes

up on Mt. Suribachi, Iwo Jima.” As the battle continued and three

of the marines pictured are killed, AP printed one of the most famous

photographs to come out of the war. It distributed to the news media

in 17 1/2 hours---an unheard of speed for pictures from the front.The widespread

appearance of this image, while the battle was still front

page news, amazed the viewer, and probably added an immediate boost

to its future as an icon.