|

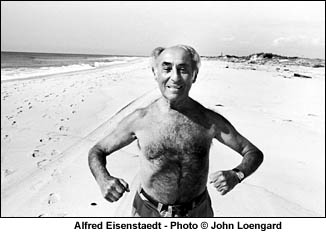

Alfred Eisenstaedt

by John Loengard

|

|

I will be remembered when I’m in heaven,”

said my friend Alfred Eisenstaedt. “People won’t remember my name, but

they will know the photographer who did that picture of that nurse being

kissed by the sailor at the end of World War II. Everybody remembers that.”

The photograph, however, was never one of his favorites. He preferred one,

for example, that shows a young woman seated in a box adjacent to his at

La Scala opera House in Milan. He took it in 1934 for DIE DAME, a German

fashion magazine. Never a slave to captions, Eisenstaedt didn’t get the

lady’s name, and the magazine did not publish the picture. No matter. “I

started as a ‘pictorialist,’” said Eisenstaedt, “and I still always look

for beautiful pictures.

“I always arrive as a friend. If somebody says, ‘I don't want to be photographed

on this side,’ I don't do it,” said Eisie. “I do not photograph blood or

war or the homeless. I would not want anyone to photograph me stretched

out on the subway steps.” Remember, Eisenstaedt was the sole survivor in

his artillery battery, when a British shell struck at Verdun; his family

lost all its savings in Germany’s post-World War I inflation; and being

a Jew, he was forced to leave home by Hitler. He might have said, you want

to see what's bad? What's awful? I've already seen that, close up.

“I always arrive as a friend. If somebody says, ‘I don't want to be photographed

on this side,’ I don't do it,” said Eisie. “I do not photograph blood or

war or the homeless. I would not want anyone to photograph me stretched

out on the subway steps.” Remember, Eisenstaedt was the sole survivor in

his artillery battery, when a British shell struck at Verdun; his family

lost all its savings in Germany’s post-World War I inflation; and being

a Jew, he was forced to leave home by Hitler. He might have said, you want

to see what's bad? What's awful? I've already seen that, close up.

“I'm rereading my diaries,” Eisie told

me when he was 94. “I cannot believe that any photographer today works

as much as I worked in the past. I worked day and night. I arrived sometimes

at three o'clock in the morning in Washington. I finished up in the afternoon,

and they’d tell me, Go to Detroit or somewhere. I slept on trains. I worked

day and night."

When doing stories Eisenstaedt worried.

While photographing each member of John F. Kennedy’s cabinet in 1962, he

drove a reporter wild worrying what suit he should wear to a session with

the Secretary of Defense, and what tie for the Secretary of the Treasury.

In the 1980s, after I’d asked him to photograph Chicago’s first woman mayor,

he wanted my opinion on whether to bring his autograph book. Would she

be a historic figure? He decided she would not. Eisie was infatuated with

celebrity and was a celebrity himself, but where other star photographers

might be prima donnas and want to be treated specially, Eisenstaedt did

not. His pictures spoke for themselves. Where Margaret Bourke-White or

Robert Capa might handle certain subjects superbly, Eisenstaedt handled

all subjects superbly. “I see picture possibilities in many things. I could

stay for hours and watch a raindrop. I see pictures all the time. I think

like this,” he said. “But if I do not see a picture. I do not take my camera

out of the bag.” It was as simple as that.

He worried about anything except finding

a picture. He worried about when he would eat lunch, or what simple food

he might have, or who would pay. He rarely took pictures after dark. He

ate only a very light supper and went early to bed. He awoke before dawn.

At the age of 93, he said, “Lately, I always get up between 4:00 and 4:15

and do three different exercises. Between six and seven o'clock, I read

the New York Times. From seven to eight, I sit in a dark room and listen

to music, to tapes. Radio news and music. That's what I do in the morning.

I feel very relaxed. But I listen only to classical music, not rock music.”

“They called him a photo-reporter, but

he's not,” his colleague and mine, John Phillips, noted. “You know what

Alfred's genius is? Making himself look smaller than he is. This is why

Sophia Loren can take him up in her arms like a baby panda and kiss him.

I mean she couldn't do that with me. He makes himself look small, and everybody

wants to help and protect him. When he takes a picture, he crouches down,

he braces his whole body like a piece of granite, and he can hold his camera

steady for half a second, which is incredible. He’s a great magazine illustrator,

but he never dreamt up a story. You set him up with the Pope, you'd get

marvelous pictures of the Pope.”

Eisie always dressed carefully. He was

always polite, and always curious, but never familiar. Despite our many

conversations, I have no idea if he had brothers or sisters, or if he’d

been married before he married his beloved Kathy in the late 1940s. I knew

he had arranged for his mother to get out of Germany in 1936, but he never

mentioned the Holocaust. I know nothing about other friends or relatives.

He did not wear his heart on his sleeve, but on the other hand, he was

concerned whenever a colleague was ill. Once I was in bed for a few weeks

with a bad back. He was one of the two from LIFE’s staff who paid a call.

Eisie was self-centered, I suppose, but

in the way an orchestra conductor is. One day, in the 1960s, he brought

me along to Karl Heitz, Inc. to look at a new lens, and I saw the Eisenstaedt

that wasn’t in the office where photographers behave like fish out of water

at best. Entering the showroom he became the taut, stern boy from Prussia.

He seemed taller (“I say I’m 5'4” tall, but people say it's 5'3”. I don't

know. I have no idea. I don't care. I'm small. I'm a midget.”). Sales people

bowed and scraped like piano salesmen faced with Vladimir Horowitz. The

king had arrived and he played it to the hilt. “I was educated by a very

famous editor, Wilson Hicks,” he told me. “He gave me an assignment to

go to Hollywood and photograph all these great movie queens there. He said,

‘Don't be afraid of all these movie queens. You are a king in your profession.’

I've never forgotten that. Not that I feel like a king, but don't be afraid

of people. The less you are afraid, the better.”

I must point out that Eisie would repeat

verbatim anecdotes in his repertoire. He would not repeat them directly

to the same listener, but an interview in 1995 would contain stories that

are word-for-word what an interviewer heard in 1970. He was a performer,

and a good one.

Dan Longwell, LIFE’s very first picture

editor and later a managing editor always called Eisenstaedt, “Alfred”

but everyone else in the world, from lab technicians to Henry Luce, called

him “Eisie.” That is, except for Thomas Hart Benton, the crusty, independent

regionalist painter who was one of Jackson Pollack's teachers. Said Eisenstaedt,

“I photographed Benton every year on Martha’s Vineyard. He was my friend,

and he is the only person who's ever called me 'Alfie.'

“We were all individualists,” said Eisenstaedt.

John Loengard was born in New York City

in 1934, and received his first assignment from LIFE magazine in 1956,

while still an undergraduate at Harvard College. He joined the magazine's

staff in 1961, and in 1978 was instrumental in its re-birth as a monthly,

serving as picture editor until 1987. Under his guidance in 1986, LIFE

received the first award for "Excellence in Photography" given by the American

Society of Magazine Editors. In 1996, Loengard received a Lifetime Achievement

Award "in recognition of his multifaceted contributions to photojournalism,"

from Photographic Administrators Inc. Books of Loengard's photographs include:

Pictures Under Discussion, which won the Ansel Adams Award for book

photography in 1987, Celebrating the Negative, and Georgia O'Keeffe

at Ghost Ranch. His most recent book, LIFE Photographers: What They

Saw, was named one of the year's ten top books last fall by the NEW

YORK TIMES. |

“I always arrive as a friend. If somebody says, ‘I don't want to be photographed

on this side,’ I don't do it,” said Eisie. “I do not photograph blood or

war or the homeless. I would not want anyone to photograph me stretched

out on the subway steps.” Remember, Eisenstaedt was the sole survivor in

his artillery battery, when a British shell struck at Verdun; his family

lost all its savings in Germany’s post-World War I inflation; and being

a Jew, he was forced to leave home by Hitler. He might have said, you want

to see what's bad? What's awful? I've already seen that, close up.

“I always arrive as a friend. If somebody says, ‘I don't want to be photographed

on this side,’ I don't do it,” said Eisie. “I do not photograph blood or

war or the homeless. I would not want anyone to photograph me stretched

out on the subway steps.” Remember, Eisenstaedt was the sole survivor in

his artillery battery, when a British shell struck at Verdun; his family

lost all its savings in Germany’s post-World War I inflation; and being

a Jew, he was forced to leave home by Hitler. He might have said, you want

to see what's bad? What's awful? I've already seen that, close up.