|

|

THE

VIOLIN MAKER'S SON

by Susan Markisz

for The New York Times

March 1, 2001

Rye, NY

I was glad I went to work today. I should stress that I enjoy going to work

most days, but when an editor prefaces an assignment with "this sounds

kind of interesting," I'm usually hooked long before I take out my camera.

Robert Isley III is a "Luthier" which is French for violinmaker. Robert's

six year old son, Robert Clark Isley was with his dad the day I went to his

studio to take pictures of him crafting his violins, which take over 120 hours

of meticulous work for each instrument.

As my camera's frame counter headed numerically upward on my second or third

roll of film, my defining moment had not yet materialized.

|

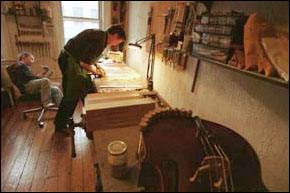

The setting sun provided warm light coming in from the window of the small second-floor studio. Robert Isley, violinmaker, had several violins in various stages of development. One could barely imagine that he was crafting a $12,000 instrument, as he "thicknessed the rib stock," removing the bulk of wood from thin strips of wood with a block plane on his worktable. Later on, the wood took on the sensuous shape of the instrument we associate with philharmonic orchestras. |

Robert Isley III, a Violinmaker, working in his studio on one of his

handmade violins.

|

Robert appeared to be just a tad uncomfortable by his son's presence, (more on my behalf, I think), but I reassured him by saying: "He's fine, he's just fine." In truth, however, the little guy appeared at odd times in my viewfinder. I would get a nice picture of his dad, backlit by the waning window light, for example, with young Robert nearby, swinging around on a swivel chair, with only his leg sticking out. I wanted him either in the picture or out, but I did not have the heart to ask him to move. |

|

|

Robert Clark Isley, 6, hangs out as his dad thicknesses

the rib stock, planing wood to make a violin. |

The son didn't figure in any significant way into the story, which was about

instrument makers and their craft. (Earlier in the day, I had photographed a

fellow making drones and chanters for bagpipes). But I knew in my heart that

there was something to this unfolding scenario that would result in a picture.

Something about the child's presence and his relationship to his dad, kept my

patience for imagery intact. I photographed around him, and I waited for an

illusory moment, which I could no more have put into words than I could have

composed the picture myself. I was not sure what it was I was waiting for, but

I was certain, if I waited long enough, it would happen.

The warm afternoon sun had practically vanished now and I was left with the

remnants of a dusky blue light coming in the window. I took out my flash, put

it on a cord off camera and bounced the powered down strobe off the ceiling.

Robert Isley mixed in a little bit of color to the varnish that he uses and

then proceeded to work on a violin, lightly brushing some of the lustrous mixture

on the wood, giving it a fine patina. Young Robert, meanwhile, had put down

his Game Boy and had become intrigued by the finishing process. I realized that

something was happening here. I was into my third roll of film; half of it with

an imaginary latent image, like an artist's blank canvas, the potential for

a really nice picture in the palette of my mind's eye. Painters may take umbrage

to my analogy but photography doesn't just happen. It may require technology

or circuitry of some kind, but ultimately it requires a vision, or an idea,

or the seed of an idea. A seed is what I was working with.

Suddenly, the violinmaker's son, climbed up on a chair behind his dad, and put

his arms around his dad's neck, peering over his shoulder, intently studying

the application of varnish to the violin. My heart started beating faster, knowing

that this is what it was I had been waiting for. I shot three or four frames,

as six year old Robert Clark Isley surrounded his arms around his captive dad's

shoulders for a few moments, at rapt attention as his dad worked meticulously

on the violin. Almost as quickly, I realized there might be a better perspective.

I got down on the floor, looked up at the father and son and saw the violins

hanging from a rack in the background and pressed the shutter twice. I couldn't

have asked for a sweeter or more genuine moment. Just as quickly, the moment

was over, and so was my assignment.

|

| Violinmaker Robert Isley III applies varnish to one of his handcrafted

violins, as his son Robert Clark Isley peers intently over his shoulder.

Copyright 2001 Susan B. Markisz for The New York Times |

The moment between father

and son speaks volumes about parenthood, and patience and the craft of making

something fine. A relationship, a violin, a photograph, a moment.

Susan B. Markisz

March 2001