|

WESTON NAEF is

curator of photographs at the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles; previously,

he had been in charge of photographs at the Metropolitan Museum of Art:

AIDS has had a tremendous impact on photography. I lived in New York

City from 1969 through 1984, which was a heyday for photography in general.

It also coincided with both the rise of photography as a major form

of creative expression for a younger generation and the rise of the

collecting of photographs by an older generation. For reasons that cannot

be fully explained, both on the collecting and creating sides, there

were a disproportionate number of individuals who eventually came to

be impacted by the AIDS crisis.

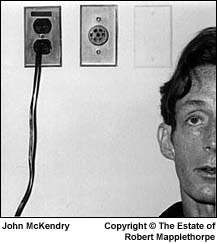

Two

of those people, in particular, have special meaning for me. One is

Sam Wagstaff, a curator of 20th century art who was first a collector

of paintings and sculpture, and then a collector of photographs. Sam

truly discovered Robert Mapplethorpe and believed greatly in Robert’s

genius. Sam helped Robert by introducing him to people who could instruct

him and advance the creative side of his life, and eventually made it

possible for Robert to achieve complete financial independence. Two

of those people, in particular, have special meaning for me. One is

Sam Wagstaff, a curator of 20th century art who was first a collector

of paintings and sculpture, and then a collector of photographs. Sam

truly discovered Robert Mapplethorpe and believed greatly in Robert’s

genius. Sam helped Robert by introducing him to people who could instruct

him and advance the creative side of his life, and eventually made it

possible for Robert to achieve complete financial independence.

I was a close by-stander to the development of their relationship, to

the unfolding of Robert’s creative side and to observing Sam’s

nurturing of this process and to the early formation of a collection

of photographs that I am proud to say has been in the custody of the

J. Paul Getty Museum since 1984. Sam died of HIV-related problems in

1987. Robert did subsequently as well, in 1989.

The HIV epidemic brought about many changes. It caused the demise of

many talented individuals in the art world, but it also brought together

people in unexpected ways as they attempted to deal with an illness,

of which the means of transmission were then obscure and for which initially

there were no effective treatments. Unprecedented alliances between

arts organizations and newly founded charitable organizations came into

being in order to raise money to try to alleviate suffering, to care

for the sick, and to find a cure, or at least to understand the causes

of the epidemic. It also drew together sufferers and survivors in a

new kind of compassionate community. This malady was a crucible of suffering

from which, however, some positive elements emerged.

AIDS

shaped many photographers’ work, including bringing greater depth

to the later stages of Mapplethorpe’s development as an artist.

Similarly other artists like Peter Hujar, whom I met through Robert,

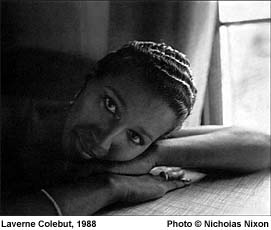

were influenced by the course of their illnesses. Other photographers

were moved to respond to the sickness around them, like Nicholas Nixon,

who photographed individuals using a tripod-mounted view camera that

exposed negatives 8 by 10 inches in size. His was not a quick take.

He produced a studied analysis of the geography of a person’s face

and of a body in the process of withering. Nicholas chronicled the visual

results of the ailment with such extraordinary and poignant detail.

And then Nan Goldin, younger than Sam Wagstaff, circulated in a community

ravaged by AIDS as well, to which she reacted sensitively with her camera. AIDS

shaped many photographers’ work, including bringing greater depth

to the later stages of Mapplethorpe’s development as an artist.

Similarly other artists like Peter Hujar, whom I met through Robert,

were influenced by the course of their illnesses. Other photographers

were moved to respond to the sickness around them, like Nicholas Nixon,

who photographed individuals using a tripod-mounted view camera that

exposed negatives 8 by 10 inches in size. His was not a quick take.

He produced a studied analysis of the geography of a person’s face

and of a body in the process of withering. Nicholas chronicled the visual

results of the ailment with such extraordinary and poignant detail.

And then Nan Goldin, younger than Sam Wagstaff, circulated in a community

ravaged by AIDS as well, to which she reacted sensitively with her camera.

What I experienced in New York, first of all, were the deaths of people

who were very, very important to me as friends. Then, to see history

changed not only as a result of their actions through creative works

but, by denying us what they might have created if they had lived longer.

|