“No one ever lost his job covering the news.” So said CBS

News New York Bureau chief, Christie Basham, twenty years ago during

one of the innumerable budget cuts.

Today, I’m not so sure Christie’s statement holds true.

The world of television news has changed dramatically during those

two decades. In 2001 the bean counters seem to hold sway over the

journalists, and it is entirely possible that someone could be fired

covering the news.

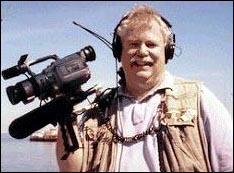

In

1976, Martha and I were one of the first crews to change from film

to video (3/4" U-matic back in those early days). As a result,

we got a lot of work because there were so few freelance ENG crews.

And the system worked much differently– the networks actually

covered news stories themselves, rather than rely (as today) on local

stations and news services.

In

1976, Martha and I were one of the first crews to change from film

to video (3/4" U-matic back in those early days). As a result,

we got a lot of work because there were so few freelance ENG crews.

And the system worked much differently– the networks actually

covered news stories themselves, rather than rely (as today) on local

stations and news services.

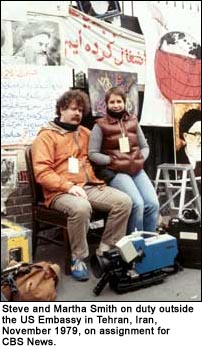

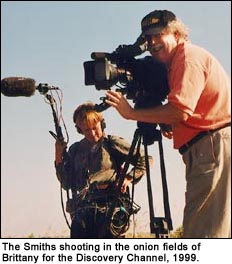

Someone recently wrote that the late 1970's and early 1980's were

the “Golden Age” for ENG crews. Balderdash!, I thought when

I read it. But upon reflection, it’s probably true. Those were

the halcyon days. Martha and I got to travel around the world, several

times, on stories that today would not warrant sending a crew. For

example, in 1981, CBS pre-positioned two crews in Ankara for the visit

of secretary of state Alexander Haig. Then, while he went on to another

stop, we were to jump ahead to Rabat to await his arrival there. Two

crews! For the secretary of state, no less. There’s no way that

would happen today. I’m not even sure the networks would provide

that kind of coverage for the president.

The 1986 presidential election in the Philippines was probably the

most extravagant use of news resources I can recall. CBS had seven

or eight crews, a private satellite uplink, and the ability to take

in live feeds from three different locations at one time. The network

even sent over a team from their polling service to setup exit polls

at the voting stations (a monumental failure). The Philippines was,

in many ways, the last hurrah.

Times have surely changed.

Twenty years ago it was the norm to send a crew to cover even the

most mundane of stories. We got hundreds of assignments over the years

to shoot things like: a pile of coal at a Pittsburgh-area power station

during the 1977 energy crisis, a shot of former president Gerald Ford

getting out of a car at the Army War College (and tripping over the

curb), the imploding of an old hotel in Atlantic City. In all cases,

getting to these places required 3-5 hours of travel, just to tape

a single element for a larger story. In 2001, if the network even

deigned to use such imagery, they would pick it up from their affiliates

at virtually no cost.

Back in the 70's and into the mid-80's, CBS News had a “Net First”

policy. That meant that the hugely popular “Evening News with

Walter Cronkite” could declare first dibs on any story or images.

Net First ensured that the

video would be exclusive to the Cronkite show, and only after it had

aired there would it be released for distribution to other CBS broadcasts

and station affiliates. In 2001, the images you see on the “Evening

News” have already been shown all-day long on outlets like CNN,

and then again on your local news. The chances of seeing exclusive

footage of breaking news on the nightly network programs is now almost

nil.

This

is due mainly to the growth of news feed services, with names like

Newspath and Newsource. The concept has been around for decades. ABC

used to call its daily late afternoon half-hour relay of stories the

Daily Electronic Feed. ABC/DEF. Get it? Today, one of these “video

wire services” may relay one or two hundred pieces each day,

sometimes operating 24/7. The feeds create two phenomena: 1) they

reduce the importance of the daily network flagship news broadcasts,

and 2) because hundreds of stations across the country, and even around

the world, are swapping stories and pictures, the cost of covering

national and international events has decreased (and that makes the

financial people smile).

This

is due mainly to the growth of news feed services, with names like

Newspath and Newsource. The concept has been around for decades. ABC

used to call its daily late afternoon half-hour relay of stories the

Daily Electronic Feed. ABC/DEF. Get it? Today, one of these “video

wire services” may relay one or two hundred pieces each day,

sometimes operating 24/7. The feeds create two phenomena: 1) they

reduce the importance of the daily network flagship news broadcasts,

and 2) because hundreds of stations across the country, and even around

the world, are swapping stories and pictures, the cost of covering

national and international events has decreased (and that makes the

financial people smile).

Another change from the old days: in 2001, the number of freelance

video people has increased from a phone booth full to a stadium full.

Nowadays, anybody and everybody can, and does, shoot video. Seeing

amateur images on the nightly news is common - some of the most infamous

images of the past decade were made by non-professionals (e.g., the

Rodney King beating in LA, the fiery Concorde flying to its doom).

None of the front office people seem to understand that the photographer’s

skill is a finely honed one; that experience in the field is a valuable

commodity. I guess the decision makers figure that if they can shoot

their sons’ birthday parties on their little handycams, a producer

or a reporter can shoot a news story. CNN is trying this in a big

way, having purchased multiple sets of mini digital cameras and edit

packs to hand out to non-photographers. This system might be fine

for those rare personalities who possess a strong auteur streak, and

who excel at the myriad skills necessary to produce, write, report,

photograph and edit a story. But for the other 99.9% of broadcast

journalists, the collaborative nature of news coverage works just

fine, thank you very much.

Even the prestige news broadcasts are not immune to the bean counters.

A producer friend at a highly esteemed morning news program told me

recently that his executive producer called him on the carpet for

letting a camera crew put in for overtime. It seems that the crew

worked for a different broadcast one day, traveling that night from

New York to Ohio to be ready for an early morning interview for my

friend’s show. The OT was charged to his show, not the other,

and hence the reaming out.

Things aren’t a whole lot better at a top rated weekly magazine

show. Producers there are watched over by a Senior, who happily second

guesses their needs and tells them they’ve booked too many shoot

days. “Cut $10,000 from your budget,” is a familiar refrain

there today. And this is a show that brings the network tons of revenue.

So where does this all lead us in the coming decade?

Crikey, I dunno.

I suspect the bean counters will continue to prevail, squeezing deeper

and deeper cuts out of the news divisions (or getting out of the news

business entirely). The globalization of news coverage by a steadily

diminishing number of outlets can mean huge cost savings for the conglomerates,

but at the cost of journalistic diversity and integrity. And I fear

that. Do I really want AOL/TimeWarner, Viacom, Fox and Disney to control

the vast majority of the news I can watch or read?

We should be scared by “synergy,” where the conglomerate’s

various divisions interlink their efforts, usually in the nature of

promoting a product. The synergistic possibilities at AOL/TimeWarner

are mind boggling. Warner can produce a film, the making of which

can be promoted on HBO, the opening of which can be hyped on AOL,

and reviews of the film can appear in Time Magazine and on CNN. Still

other synergies come to mind. The film’s finances can be covered

in Fortune and Money and on CNNFN, and celebrities can be splashed

across the pages of People. A year down the road, HBO can show the

film, and, after it’s become a classic, TCM can air it too. The

line between news and entertainment, already blurred, stands to disappear

altogether.

And jeez, what happens if a good story is inimical to the parent company?

A journalist may say, “run it.” But a corporate manager

may say, “run it and you’re fired.” Sooner or later,

that kind of pressure will force the real journalists out, to be replaced

by corporate-compliant people (a phenomenon that is already beginning

to happen).

The business of television journalism today places too much emphasis

on the bottom line and not enough on serving the viewer. The Golden

Age of TV news is dead. And, unfortunately, I don’t think it

will be too long before Christie Basham’s maxim is proved wrong.

Will the pendulum ever swing back? Don’t hold your breath.