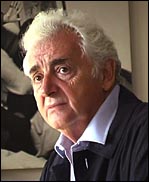

ON THE ROAD WITH HARRY BENSON By David Friend He was just steps from Bobby Kennedy the night the senator was shot, steps from Coretta Scott King at her husband's funeral, steps from Richard Nixon the day the president resigned in disgrace. He was on hand for the Freedom March through Mississippi, the Watts riots, the I.R.A. hunger strikes, the fall of Czechoslovakia and Romania and the Berlin Wall. He was invited by Jackie Kennedy to shoot her daughter Caroline's wedding (to Edwin Schlossberg), invited into Michael Jackson's bedroom (to take baby pictures of Jackson's son Prince), invited into Elizabeth Taylor's hospital suite (to photograph the star, bald as a tulip bulb, after brain surgery). Flip through the new book Harry Benson: Fifty Years in Pictures (Abrams) and one gets the eerie impression that for half a century he has been nothing less than photojournalism's Zelig--the man who happens to materialize, with a camera, whenever history envelops the high and mighty. He covered every president since Eisenhower, the first US casualty in Bosnia, firefights in Kosovo, the pall of smoke above the Twin Towers' wreckage on September 11, 2001. Before there was a 24-hour news cycle, before there was a CNN or a FOX, there was The Fox, a lone lensman from Scotland with a hungry eye trained upon the world's public prey.

"The plane pulls up to the ramp," Eppridge continues, "and the door opens. A Pan Am stewardess comes off, and out come the four Beatles. Then this character comes out right behind them, and he starts posing them. Eddie and I looked at each other and said, 'Who is that?' We had no idea. It was Harry Benson's first trip to the United States. It's been going on like that for years. Every time you'd know what the best spot is, who shows up in that spot? Harry Benson." In fact, Harry's images of Beatle George Harrison, who succumbed to cancer on November 30, appear in the tribute sections of the new issues of Rolling Stone, Time and Newsweek. Over the years, I've had the opportunity to travel the world with Harry Benson. On assignment for LIFE and VANITY FAIR, we have covered conflicts in Afghanistan, Pakistan, Poland and Oman, terrorism in Kuwait, Israel and the West Bank. We've wrangled exclusives with our share of notables (Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, Bill Clinton), scoundrels (CIA double-agent Aldrich Ames, terror-cleric Omar Abdul Rahman) and embattled patriots (TWA hostage Peter Hill, Iran-contra pin-up Oliver North). We've gone from the Beatles' London archives to Michael Jackson's Neverland, from drug dens in Brooklyn to the Milwaukee Brewers' dressing room, from a shock trauma unit in Baltimore to the smoldering ruins of Ground Zero. Now, as his stunning new book gets rivulets of ink and accolade, it's time to pull back the first-class curtain. Along with all those frequent-flier miles, I have managed to accumulate a primer of sorts--a collection of wise, brogue-borne pearls that might be called Harry Benson's Rules of the Road. RULE # 1: Never to get too comfortable on a story. No matter how bleak things seem, they can always get worse. In 1982, we were in Poland, covering the Solidarity resistance movement for LIFE. The country was in the grip of martial law. Communist authorities were suspicious of any contact with Lech Walesa or any member of his opposition coalition. Through underground contacts, we had located two Solidarity activists, fresh out of prison, and had brought them to a forest clearing on the outskirts of Warsaw to conduct a clandestine photo-and-interview session. The pair had brought along a cache of pictures, snapshots of their imprisoned compatriots, which they had recently smuggled out of jail. Little did we know that the sylvan glade we had chosen for our meeting was actually on the fringes of a military installation. As soon as Harry took out his cameras, a transport van pulled up. Armed soldiers hopped out and announced that we were being placed under arrest, along with our companions. They confiscated Harry's equipment and film, then took my notebooks for good measure. Moments later, the young translator who was accompanying us raced nervous fingers through a Polish-English dictionary, fumbling as he tried to explain our predicament. He stopped at a page and pointed to one word: "Espionage." Over the course of five long hours, we managed, miraculously, to talk our way out of it, all the while feigning outrage at our detention. But for one grim afternoon, our fate was in the hands of a cadre of swaggering thugs with guns. Before our release, near the very end of the ordeal, Harry pulled me aside and offered a chilling, if hilarious, observation--part augury, part admonition. "You see that guard over there?" he whispered. "In a week you'll be offering him a blow job for a cigarette. And in six months," he went on, "Steve Robinson [our editor in New York], will be having an affair with Nancy"--then my wife-to-be. RULE #2: Go for the center, first. "Too many photographers dance around the edges of a story," Harry likes to say. "They're afraid of the center. I go for the heart of the story the minute I get off the plane. The first-- and last--pictures you take are often the key pictures of a story." This photo-essayist can also isolate that perfect moment that transcends a story, capturing the essence of a personality or event in a single frame. No wonder he has been able to hit that rare photographic grand slam: conjuring an emblematic, era-defining image in four successive decades: the Beatles' pillow-fight (60s), Nixon's resignation (70s), the Reagans dancing (80s), Gulf War leader Norman Schwarzkopf giving the thumbs-up in an open helicopter (90s). RULE #3: Keep in fighting trim, Fleet Street style. I once wrote the following in London's Sunday Times Magazine, about Harry's rough-and-tumble youth: "As a boy, Benson, whose father was the curator of Glasgow's Calder Park Zoo, had his share of brawls on the tougher side of town. Following stints as a minor-league goalkeeper for various Glasgow-area teams, Benson began shooting early-morning weddings at local churches, developing the film in a shed in his garden, then hustling the finished prints to the bridegroom within three hours. At 27, he jumped into Fleet Street. After a spell at the Daily Sketch, Benson made his mark at the Daily Express between 1958 and 1964, becoming the darling of the paper's proprietor, Lord Beaverbrook. "Benson was renowned for his stealth. He once swiped unsuspecting journalists' shoes from outside their hotel-room doors (in order to get a jump on them in the morning). On another occasion, after three of his competitors plotted to bounce him off a party guest list (so that he couldn't photograph an evening affair), he repaid their sabotage in kind: retagging their bags at an airport luggage counter to ensure that their film would take a wayward route to the home office--by way of Rio. "Benson hid in Westminster Abbey to cover royal weddings, braved high-speed car chases to land exclusives with the likes of Winston Churchill and Prince Philip, and hid in a palm tree to shoot an unauthorized picture of Elizabeth Taylor on the London set of Cleopatra. Frank Spooner, Benson's former picture editor at the Express, recalls: 'Harry would always appear to have luck on his side. He always seemed to be getting the big shot. Harry made things happen. That's what happens to good journalists. And I think he was about the best there was on Fleet Street.' "

Harry is a scrapper. He looks at every assignment, every day, as the main event--a chance to confront and capture his subjects (and to compete against his peers) at history's white-hot center. If a great picture is to be made within a ten-block radius of his Kelly-green pocket square, Harry's journalistic antennae suddenly twitch. He senses a photograph developing, somewhere out in the great gray distance. Then, like Clark Kent or Bruce Wayne, he's suddenly transformed: cloaked in concentration, ready for battle, beckoned to the scene. I remember one evening in rural Vermont. Harry and I were on assignment and decided to take a walk after dinner, in the winter chill, to ease our anxieties about the next day's shoot. For several blocks the only sound that grazed the darkness was the crunch of our boots on new snow. We followed a country lane, its curve bearly visible in the night. In the distance, a streetlight shone and we wandered toward it, without speaking. Upon approaching the light, we spotted a lone horse near a roadside fence, and we stopped to listen to it stomp in the cold, breathing in and out with the evening. Its labored breath, while somewhat soothing, unsettled us slightly. In the morning, we knew, we would become the first reporter-photographer team to set foot on the secluded estate of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, the Russian writer and dissident, then living in nearby Cavendish. Ours was to be the first-ever "at-home take" with the exiled author--not counting some snapshots by New York Times writer Hilton Kramer--since Solzhenitsyn had fled the Soviet Union a decade before. We watched as the horse made small clouds in the night air. Then, suddenly, I saw my companion sidle over to the funnel of white cast by the streetlamp. Without explanation, he hunched over, struck a boxer's pose and, fists clenched, began jabbing the air in front of him. He mumbled a little, making little pumph-pumph sounds, as he threw punches at the night. "What the hell are you doing?" I asked him. "You only get one chance David," he remarked, "I gotta be ready tomorrow." RULE #5: Speed is all. "Speed isn't everything," says Harry. "It's the only thing." Much of Harry's success can be attributed to his fearless drive to capture spontaneity at all costs, in his raw energy and stamina and resourcefulness, in his belief in speed over stasis, truth over beauty, cunning over compromise, journalism over artfulness. "I want photos that are spontaneous," he insists, "[I don't] set up lights for four hours [in the time it would take] to watch a fly die. I'm after pictures with surprise, pictures with air in them, pictures that let people be themselves. I don't want to impose on them just what I think they are. They should be themselves. If you're too controlling [and] you set things up in a studio, [you risk letting] rigor mortis set in." That instinct to produce "pictures with air in them" is evident throughout Benson's new book. The collection brims with images that seem so fresh and energetic they might as well have been infused with pure oxygen: a pride of Harrow schoolboys opening hearts and arms to their academy's most illustrious alum, Winston Churchill; Monaco's Princess Caroline reigning over a ballet class; prize-fighters Liston and Clay in two tableaux of ringside frenzy. RULE #6. Minimize your contact with the office. One evening in 1983, after the Soviet Army invaded Afghanistan, Harry and I were strategizing in his hotel room in Peshawar, Pakistan, on assignment for LIFE. The next morning we were to be spirited across the border by representatives of a militant Islamic faction that was holding several Russian prisoners of war. Our intention was to be the first team from a U.S. magazine to photograph and interview the Soviet combatants being held in Afghanistan by the mujahedin. Others had talked with P.O.W.s at rebel hideouts in Pakistan. But we needed to penetrate the war zone -- to travel into Khost and beyond -- to secure a true exclusive. Several days before, we had acquired invaluable gear for the trip: loose-fitting tunics and headgear so that we could pass, undetected, through numerous checkpoints on our way into the mountains. In preparation, we had been blindfolded and taken to safe-houses in Pakistan to meet a handful of other Russian soldiers. Tomorrow, Isha'allah (God willing) we would meet with their compatriots in Afghanistan. That night, as we readied for our sojourn, the telephone rang. "Don't answer it!" Harry warned, holding up a hand. "If you do, you'll be on the next plane back." He took the call, and naturally, it was New York on the line. Coming up against a looming deadline, our editors were getting nervous. They wondered if Harry could hand me the film he'd already shot so that I could return home immediately. At least this would give them a sense of how the piece was shaping up, and would allay their fears; Harry could finish the story himself. "I'd love to do that, Steve," Harry lied. "But David's already about five hours from here. Somewhere I can't tell you about on the phone. Dressed like an idiot." "Don't worry," he went on, "we'll be home with the story in time for the close." Harry smiled as he cradled the receiver. "If you had just picked up that phone, you'd have traveled half-way around the world to just to be a messenger boy. You'd never have set foot in Afghanistan." We got our exclusive over the course of the next three days, passing within 14 miles of the Russian front. And we did it together, thanks to Harry's ruse. RULE #7: Worry, worry and worry some more. Before he even trips a shutter, Harry calibrates an internal Geiger counter of worry, plotting out the possible pathways through which the story might carom or ricochet. Once in the field, he allows few distractions. The assignment is all. On the road, he practices a Ramadanian regimen, often refusing food during daylight hours in order to make him more ornery, he says, to keep his attention more in synch with the edgy Zen of a story's flow. "If I'm relaxed and happy," he says, "I'm finished. As soon as that happens, it's 'Goodnight, Vienna.' " RULE #8: Be a lone wolf. According to Harry: "If the pack is going this way, I'll always go that way. This is not a team sport. You only gather strength from your own momentum. You don't see [Richard] Avedon hanging around [on assignment] with a bunch of guys going out for Chinese dinners." RULE #9: Every story is some version of Star Wars. Harry has developed the equivalent of a psychic's powers of premonition, able to anticipate the shifting patterns and rhythms that inevitably emerge on a shoot. He is equal parts Sean Connery and Muhammad Ali; shrink and samurai; Patton and Machiavelli.

RULE #10: Keep it light. Harry is a man whose days play out with operatic brio. He relishes the good life and the good fight. For all his inner intensity, though, he possesses endless stores of friendship, good humor and charm. Harry realizes that it's important to let up on the reins, early and often, to keep a story--and life itself--in perspective. In 1980, just as the Cold War was getting decidedly frosty, Harry and I were in a helicopter over the Strait of Homurz, seven miles off the Iranian coast. The Shah had been toppled and the region was in turmoil. The Russians had sent warships to prowl the vital waterway through which oil tankers passed en route to the West. In response, President Jimmy Carter had vowed to keep the oil lanes open and to defend the Persian Gulf against foreign aggressors. Our assignment: to produce the first photo story showing the Soviet fleet. First, we found an enterprising British chopper pilot at a Godforsaken outpost on Oman's Musandam peninsula. Next, we coaxed him into taking off in foul weather across the strategic strait. Finally, we convinced him to swoop in low over the warships, so that Harry, leaning through the cargo door--his peacoat firmly in my grasp--could take pictures of Russia's menacing armada. As we hovered above the first ship that came into view, the British pilot, shouting through our headsets, explained that all it would take would be one well-aimed shot at a rotor blade, and we would be gone without a trace. "No one would ever know," he added. "We'd just be breakfast for the sharks." (Just to assure our quarry that we weren't on a spy mission, the pilot was careful to announce on his radio--on a frequency monitored by the Russians--that we were a team from LIFE magazine.) The pilot made a few passes over the fleet. And as we finished our "dive bombing" run, Harry turned to me and yelled over the roar, "What if, instead of taking photographs, all we'd done was gone in and then opened up one of those big banners? You know like 'Mario Biaagio for City Comptroller' or 'Keep The Giants Out of New Jersey'? Something really stupid." We laughed for much of the trip back to Oman. And, once on land, Harry promised the pilot a case of Heineken if he'd agree not to take other newsmen on the same trip--until our story was published, three weeks later. The pilot shook on it. We beat Mike Wallace and "60 Minutes" by a week. -

David Friend David Friend is Vanity Fair's editor of creative development. |

||||

|

Video Interview

with Camera: Dirck Halstead To watch these video

clips, you will need |

|

Harry Benson: Fifty Years in Pictures |

Photo Gallery |

Visit Harry Benson's

website at

|

Write a Letter

to the Editor |

"[I

remember Harry] when the Beatles first came to this country [in 1964],"

recalls photographer Bill Eppridge, in a passage from John Loengard's

"[I

remember Harry] when the Beatles first came to this country [in 1964],"

recalls photographer Bill Eppridge, in a passage from John Loengard's

RULE

# 4: You're only as good as your last scrape.

RULE

# 4: You're only as good as your last scrape.  Like

a seasoned whaler, Harry has covered so many stories, so consistently,

for so many decades, that he has acquired an uncanny ability to foresee

the shifting patterns and rhythms that inevitably emerge in the field.

Like a seasoned whaler, racing to locate and lure and vanquish his

catch, he can divine when and how a story's waves will break to his

advantage: WHEN a subject is likeliest to let his guard down; WHO

within the orbit of a given assignment will soon set him off target,

whether deliberately or inadvertently; HOW best to divert the attention

of a subject's minder or spouse in order to go in for he kill; WHICH

unexpected ally within the enemy camp--or even among his press corps

counterparts--will he soon enlist to assist him in his cause; WHETHER

the home office, through sheer impatience or panic, ego or inexperience,

is on the verge of endangering a story or compromising its legitimacy

by misreading the delicate lattice of courtship and intrigue that

have set the story in motion in the first place; HOW to defend an

iron-clad exclusive against all competitors--and invariable, against

devious colleagues; WHEN to turn on the charm.

Like

a seasoned whaler, Harry has covered so many stories, so consistently,

for so many decades, that he has acquired an uncanny ability to foresee

the shifting patterns and rhythms that inevitably emerge in the field.

Like a seasoned whaler, racing to locate and lure and vanquish his

catch, he can divine when and how a story's waves will break to his

advantage: WHEN a subject is likeliest to let his guard down; WHO

within the orbit of a given assignment will soon set him off target,

whether deliberately or inadvertently; HOW best to divert the attention

of a subject's minder or spouse in order to go in for he kill; WHICH

unexpected ally within the enemy camp--or even among his press corps

counterparts--will he soon enlist to assist him in his cause; WHETHER

the home office, through sheer impatience or panic, ego or inexperience,

is on the verge of endangering a story or compromising its legitimacy

by misreading the delicate lattice of courtship and intrigue that

have set the story in motion in the first place; HOW to defend an

iron-clad exclusive against all competitors--and invariable, against

devious colleagues; WHEN to turn on the charm.