|

Introduction

by Helen Buttfield

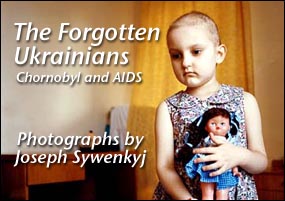

When you know what

a photographer chooses to look at, you have already learned a great

deal about him. "Those little rectangles," as Roy Stryker

so perceptively referred to photographs, tell us the rest. Joseph Sywenkyj,

who is still a very young man, has already chosen to enter a world that

most of us choose to avoid: the field of human suffering. His first

essay, in black and white, was a meditation on the suppressed, hidden

lives of two autistic brothers, whom he photographed with tenderness

and great intelligence, using his lens to penetrate their silence.

Now he has taken on the darker, more dreadful silence caused by our

ignorance of the suffering that has resulted from the explosion at Chornobyl

in 1986. He has done this by returning to the country of his fathers,

where both the language and his long familiarity with Ukrainian traditions

have been his allies. His photographs from the hospitals and orphanages

he visited oblige us to see, as if we were standing there ourselves,

the cruel deformations that radiation has imposed on children's bodies

and to feel the pain they cause. How can we bear to look at them? Because

his photographs also contain a terrible beauty that sustains us as we

take in their truth. Perhaps it is the painted blue wall that appears

behind one boy, his spine so curled backward that he seems to be rising

from a sea of infinite blue.

In another we see a field of cots with four boys, each in his cot, each

body twisted, each wrapped in his own pain. We see the first one, then

a second, and a third and finally a fourth, younger, still able to sit.

And we experience them one at a time, directly, each an individual bound

in his own world. In a third, easier to bear, the linked figures of

two attendants create a living circle that encloses a tiny infant as

if to protect him, lying prone and helpless in the radiant light. The

nurse in white, as graceful as a Botticelli goddess, seems in her beauty

to be a figure that absorbs and even transcends suffering.

Ukraine is also enduring one of the worst HIV/AIDS epidemics in Europe,

where the region's stumbling economy and dysfunctional health system

make it impossible for most of the sufferers to afford the medication

which could ease their pain and keep them alive. Sywenkyj, working with

Doctors Without Borders and other humanitarian organizations, has responded

to this crisis with equal passion, using his camera to reveal not only

the sufferings of the victims but the courage of others working to change

their despair into hope.

Photographers like Joseph, who can look steadily at the unbearable,

have a tremendous power, the power to capture images that convert ignorance

into awareness and fear into understanding, without which there can

be no change. Fortunately for the world, in the hands of such strong

and compassionate photographers these images are, as Roy Stryker said

so long ago, "one of the damnedest educational tools ever made."

Enter

Joseph Sywenkyj's Photo Gallery

|