| Let's Get

Down

December 2002

by Patrick J. Sloyan |

|

The orange arc

over Dhahran, Saudi Arabia was unmistakable. A warhead was making its

fiery reentry into the atmosphere. The modern world may well end with

such a heavenly display of incoming nuclear missiles. That flashed through

my mind as the first of Sadam Hussein‘s SCUD missiles exploded

nearby on Super Bowl Sunday, 1991.

It got my colleague from Newsday, Ron Howell, to thinking. What should

we do during such an attack, he asked? Well, I replied, get down. Look

for a ditch, a culvert, or a depression—even inside the garden

wall that surrounded our hotel. Get down was the first lesson the U.S.

Army taught me while I was briefly an infantryman.

Howell was apologetic for his ignorance shared by a generation without

compulsory military service. "I wasn’t even a Cub Scout,

‘’ he said.

Getting down is still a good rule of thumb for journalists awaiting

the start of Desert Storm II. But there are many lessons and most of

them I have learned through often-painful experience.

There was that time in 1982, just past the banana plantation, on the

road to Tyre, covering the invasion of Lebanon by the Israeli Army.

We had pulled off the road and got out of our tan Volvo sedan to watch

the volunteer army of Israel weave, stop, and then start north to Beirut

in 1982. An Israeli army officer was escorting me to Beirut. There were

gaps in the column and my escort, a major who had been in all of Israeli’s

wars, snorted at the sloppy amateurs on parade.

"Improvise, yes improvise. We always improvise because the Israeli

army cannot plan a god damn thing,’’ the major said.

We sheltered from the sun under trees. To the left, Israeli troop barges

in the Mediterranean plowed north. Then, I heard a whip-whip-whip in

the tree above us. The tanks and trucks in the column had drowned out

the noise of gunfire. But sound we heard was bullets snapping through

the leaves. I went to my knees. My training as an infantryman clicked

in: Get lower. But the major herded me into the Volvo and we were off

again.

"Probably a kid,’’ the major said. "Shooting at

the army, not us."

Still. How close was it: an inch, a foot, and ten feet? Close enough

to be unnerving. On that day, I had been a reporter for more than 25

years and it was the closest brush I had with bullets. Here I was 45,

father of four, a wife in London.

Was it worth dying for this story ? How much insurance did I have anyway?

That night, I sought the wisdom of a senior colleague, Don Schanche,

at the bar in Beirut’s Commodore Hotel. What, I asked the veteran

of International News Service, Time, Life, the Saturday Evening Post

and now, the Los Angeles Times, was the right amount of insurance? What

was dead reporter worth anyway?

"In my experience," Schanche said, rising from the stool to

his feet, "dead reporters aren’t worth much."

So true. Their dispatches lack color, flair. Facts are non-existent.

Like film from a dead photographer’s camera, such reports are

un-usable. Their real legacy is grief and pain.

So, another Rule 1 for writers and shooters, heading to Desert Storm

II: It is not worth dying.

And, death is always lurking as it was on the road to Tyre that day.

The more I thought the more the images of friends and colleagues flooded

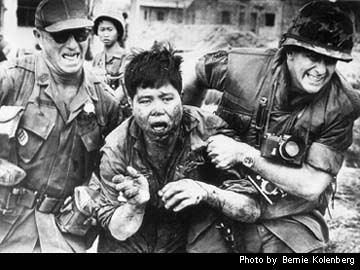

back. There was Bernie Kolenberg, a daring, inventive, witty photographer.

One day in Albany, he kept badgering former president Harry S Truman

to shift here, smile there. Finally Truman grabbed his Speed Graphic

and ordered Kolenberg to stand still. The Albany Times-Union ran two

pictures front page the next day: One of Truman with a Kolenberg’s

credit line; the other of Kolenberg with this agate credit: Photo by

Harry Truman.

Then, 13 years later I saw his name come across the UPI wire in my Washington

bureau. Killed in Vietnam while riding in a Skyraider gunship with a

South Vietnamese pilot. His plane was in a midair collision or it crashed

into a mountainside as the pilot got closer so Bernie could get a better

shot. There are differing accounts. He was working out of the AP Saigon

bureau while on leave from the Albany paper. He was the first American

correspondent to die in Vietnam. Neither his film or his body was recovered.

Too many followed, too many shooters perished for pictures that were

never published.

Those days in Lebanon showed why journalists then and now take the risks.

It would begin at dawn when the shooters suited up with armored vests

in the Commodore coffee shop. Still photographers and film crews would

strap on their gear to the sound of rock from the endless playing of

the video, "Flashdance." Some were personal friends. There

was fearless video cameraman Fabrice Mossus of ABC. A year earlier,

when gunmen began spraying Egyptian President Anwar Sadat and others

on a military reviewing stand in Cairo, Fabrice ran forward to get a

close-up of the assassins and their victims. "One of the men with

a machine gun stopped and looked at me and then turned his gun and kept

firing, " Fabrice said in recalling the day Sadat died.

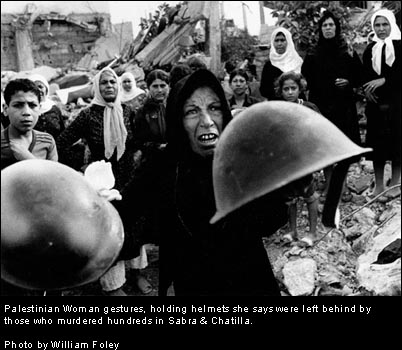

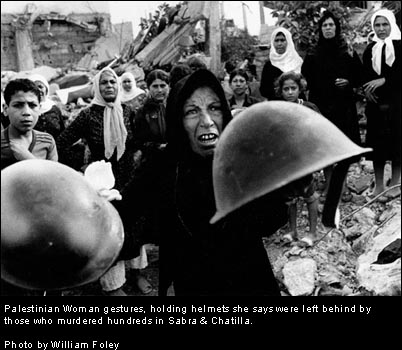

Bill

Foley of the Cairo AP buttoned the bulletproof vest tight around his

neck, grinning and sweaty from his load. He won the Pulitzer prize for

news photography the next year for covering the grisly massacre of Palestinians

in a nearby refugee camp. Bill

Foley of the Cairo AP buttoned the bulletproof vest tight around his

neck, grinning and sweaty from his load. He won the Pulitzer prize for

news photography the next year for covering the grisly massacre of Palestinians

in a nearby refugee camp.

Mercedes Benz cabs carried off the media in convoys of two or three.

Their daily destination in those days was the Shouf Mountains surrounding

Beirut. There were constant clashes between Druze, Christian, Islamic

Sunni, Islamic Shiite, Israeli, Syrian, Iranian and, eventually, American

forces.

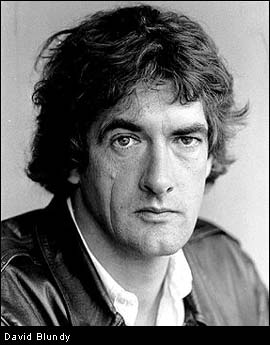

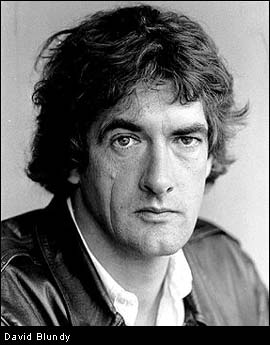

I usually traveled the mountain roads with David Blundy of the London

Sunday Times and Patrick Cockburn of the London Financial Times. Cockburn

walked like a sailor on a rolling ship because of an old leg ailment.

Blundy constantly chided him for being too slow when the things got

too dicey. "Flies are settling on you, Cockburn," Blundy would

yell. Random artillery barrages would make you scatter. It was artillery

that killed an ABC News producer and wounded others.

But Bob Simon of CBS News seemed oblivious to it all. He and his crew

would stalk the hillsides ignoring the booms, pops and crackles of gunfire.

Keith Graves of BBC television would crest ridge lines talking at the

top of his voice. Their silhouettes against the sky, their lack of stealth

and concealment would outrage any platoon sergeant.

At the Commodore bar that night, I would explain to Blundy and Cockburn

how to survive in such circumstances. We were drinking and smoking and

laughing, the aftermath of a day of adrenaline rushes. Neither had served

in the military. We grew close personally and kept up our friendships

despite different assignments.

Of course, despite the risks, Simon survived as now does,"60 Minutes,"

for CBS. Graves left the BBC but still does the odd documentary. Cockburn

followed me back to Washington before returning to the Mid-east for

the London, "Independent."

Of course, despite the risks, Simon survived as now does,"60 Minutes,"

for CBS. Graves left the BBC but still does the odd documentary. Cockburn

followed me back to Washington before returning to the Mid-east for

the London, "Independent."

Blundy, tall, thin and Hollywood handsome, stopped by my Washington

office in 1989. He was worried. A doctor had warned him the cigarettes

were leading to emphysema. Blundy left the next day for El Salvador.

A week later I coughed on my coffee at breakfast as a short item in

Washington Post reported his death.

At some unnamed crossroads, two bullets struck Blundy. "It is not

clear whether he was targeted or who was responsible,’’

said a report published by the Freedom Forum.

If I had only been there. I would have told him to get down. I would

have told him it wasn’t worth dying.

©2002 Patrick J. Sloyan

Contributing Editor

ppsloyan@starpower.net

Sloyan is a Pulitzer prize-winning reporter who has covered national

and international events since 1960. |

Bill

Foley of the Cairo AP buttoned the bulletproof vest tight around his

neck, grinning and sweaty from his load. He won the Pulitzer prize for

news photography the next year for covering the grisly massacre of Palestinians

in a nearby refugee camp.

Bill

Foley of the Cairo AP buttoned the bulletproof vest tight around his

neck, grinning and sweaty from his load. He won the Pulitzer prize for

news photography the next year for covering the grisly massacre of Palestinians

in a nearby refugee camp.  Of course, despite the risks, Simon survived as now does,"60 Minutes,"

for CBS. Graves left the BBC but still does the odd documentary. Cockburn

followed me back to Washington before returning to the Mid-east for

the London, "Independent."

Of course, despite the risks, Simon survived as now does,"60 Minutes,"

for CBS. Graves left the BBC but still does the odd documentary. Cockburn

followed me back to Washington before returning to the Mid-east for

the London, "Independent."