|

|

||||

What do you do when the situation with your foreign wife from Croatia goes south unexpectedly? What do you do when you look up and find yourself stranded in Fredericksburg, Virginia slipping into a literary and photojournalistic coma? Well, if you're like me, you look around, then you go to your storage shed, dig out the ballistic vest you haven't worn since 1997, sell anything that isn't nailed down and call B&H Photo for a couple bricks of film. If you're like me, you don't tell mom until the very last minute, but you find that she was expecting it all along and, far from being upset, says, "Well, OK honey, have a good time." Then you reflect on all and everything that has gone down over the last few years. The lost love, being marooned in a little southern town, how your dead father's helmet from WW2 showed up at the surplus store you were working in only weeks before. It came in a pile of junk from a re-enactor I had never met, with a simple paper tag in the liner bearing his name and unit in that familiar handwriting. An object he tossed on a Marine Corps turn-in pile in California back in 1946 on his way home from the Pacific. Fifty-six years and thousands of miles, it had traveled full circle to the hands of his son, on the eve of another war. That was the clincher, the omen to end all omens. There was no more debate, only a packing list. All these thoughts drifted through my mind as the strangely comforting familiarity of foreign airports drifted past in a blur.

It was a wild gamble, and a series of breaks that seemed to be more destiny than luck had me winging over the Karbala Gap on the way to the 101st Airborne outside Baghdad. There had been no real plan other than to get to Kuwait, find a way north by any means and figure out how to file once I got there. Option one, a lift to Basra with a Polish TV crew who was later captured by Fedayeen, had been superceded when my 11th hour embed came through thanks to a renegade PAO at the Kuwait Hilton. There had been 1,500 or so journos stacked up in Kuwait City trying to get up there. I don't know for sure, but carrying pictures of my horse cavalry grandfather in the Philippines, circa 1903, and my dad in the ruins of Okinawa in 1945 may have helped. I was stacked up for a few days at Camp Virginia, and

attached myself to veteran correspondent Jack Laurence, an old CBS hand

from Vietnam who was there for NPR and Esquire (See Jack's book from

'Nam, "The

Cat From Hue"). No one seemed to know where the 101st had gotten

off to, so Jack, an expert helicopter hitchhiker, led the way north.

Myself, an efficient pack mule and practiced Aide de Camp', humped the

gear until we reached our destination; 3/187th "Rakkasans."

Free food and a patch of ground to sack out on. I was home.

Ducking rounds when the lights came back on, coming down with some horrible fever, Doc Diaz nursing me back to health. (You gotta love the Army, the smallest dose of Motrin they carry is 800mg.) Cranking "Rage Against the Machine" from the Psy Ops truck with Sgt Clinton and SPC Day before setting off on a raid to capture one of Saddam's henchmen. The simple joy of rigging up running water and a toilet you could actually sit on. But best of all was the comradeship with my fellow embeds and the troops, reminiscent of the Bosnia days and our rat pack of freelancers out of Zagreb and Split, tagging along behind guys like Kurt Schork and Greg Marinovic. When I told my story of how I had been sidetracked for some years to fellow embed, Teresa B from Spain, she asked, "How could you ever give this up? I can't imagine not doing this." With multiple tours in Palestine under her belt and now this, how right could a girl be? The day I climbed into the back of that Humvee to go to the airport and head home, the last embed to leave, I felt like Oliver Twist being cast into the orphanage. My only consolation was that a cousin from Maine, whom I had never met before, was driving and I had forty rolls of solid gold in my film bag.

The next morning reality set in and I set about figuring how was I going to get out of here. Again, my guardian angels had been riding shotgun and poker night at the Special Forces safe house became my ticket home. I arrived in Frankfurt with $30 bucks in my pocket, just in time to get paid by Frankfurter Allgemeine for the one story I managed to get out to them. I took a day to catch an Ara Guler show at the Fotografie Forum International and then KLM did the rest. I arrived back in my little town, where it has been cold and raining for two weeks. I had had the feeling that this was going to be another one of those seat of the pants, brush on the skids missions and had wisely paid the rent several months in advance. So here I sit, cranking out copy, ringing up those who owe me money, sorting through 1,000+ images for the current portfolio pick and plotting my return date. All told, the war in Iraq came in at just around $4,000. Teresa was right, no other profession like it in the world. © Jim Bartlett

|

|

|

Write a Letter

to the Editor |

The

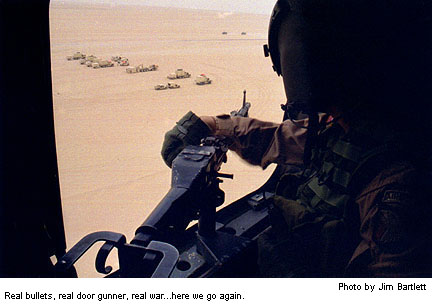

romantic reminisce, however, disappeared right about the time the door

gunner on the Chinook (a big Army helicopter) yelled, "Test fire!"

and let fly a burst of machine gun rounds towards the desert below.

"Yup, real bullets," I said to myself. "Here we go again."

With a loose accreditation from the Washington Times in my pocket, some

vague promises from UPI and not one dollar of outside support, I had

just crossed the border into Iraq.

The

romantic reminisce, however, disappeared right about the time the door

gunner on the Chinook (a big Army helicopter) yelled, "Test fire!"

and let fly a burst of machine gun rounds towards the desert below.

"Yup, real bullets," I said to myself. "Here we go again."

With a loose accreditation from the Washington Times in my pocket, some

vague promises from UPI and not one dollar of outside support, I had

just crossed the border into Iraq.  Thereafter

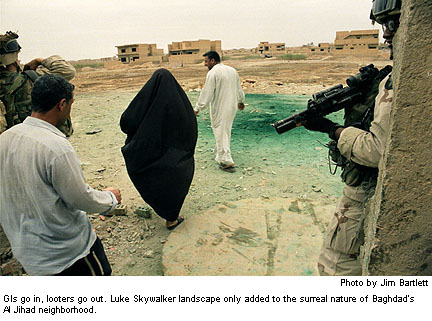

followed several weeks of hectic action as the battalion moved in and

took up zones of occupation. A Ground Assault Convoy into town, kicking

in doors as the last Baath Party positions fell, spilled blood here

and there. Patrols amongst the new neighbors, a fatal UXO incident,

coffee, cigarettes and MREs. It rolled past in a blur, six weeks feeling

like six months. Getting some copy out, running with the Special Forces,

cleaning them out at poker, watching the city come back to life.

Thereafter

followed several weeks of hectic action as the battalion moved in and

took up zones of occupation. A Ground Assault Convoy into town, kicking

in doors as the last Baath Party positions fell, spilled blood here

and there. Patrols amongst the new neighbors, a fatal UXO incident,

coffee, cigarettes and MREs. It rolled past in a blur, six weeks feeling

like six months. Getting some copy out, running with the Special Forces,

cleaning them out at poker, watching the city come back to life. When

I de-planed in Kuwait, fresh from the field and filthy, I stared vacantly

across a sea of rear echelon pouges wearing starched fatigues. I have

never felt so alone in my life. They were wise to leave me be, even

when I smoked in the non-smoking place. I guess a dirty bush hat, battered

dust goggles, discarded Iraqi ammo pouches for a camera bag and a souvenir

bayonet strapped to ones rucksack is nature's way of saying, "Do

not touch." Back at the Maha House, the cheapest hotel in Kuwait,

it was a full two hours in the shower before the water stopped rinsing

brown.

When

I de-planed in Kuwait, fresh from the field and filthy, I stared vacantly

across a sea of rear echelon pouges wearing starched fatigues. I have

never felt so alone in my life. They were wise to leave me be, even

when I smoked in the non-smoking place. I guess a dirty bush hat, battered

dust goggles, discarded Iraqi ammo pouches for a camera bag and a souvenir

bayonet strapped to ones rucksack is nature's way of saying, "Do

not touch." Back at the Maha House, the cheapest hotel in Kuwait,

it was a full two hours in the shower before the water stopped rinsing

brown.