| Dispatch:

Bunia, Congo

July 2003

by Spencer Platt |

|

Congo is frightening.

3.3 million people have died due to war in Congo in the past five years

alone, a number that stands only beside World War II in terms of war

dead. Nearly the size of western Europe, the Democratic Republic of

Congo (formally Zaire) has been cast a cruel blow by history. In the

past ten years alone it has been home to simultaneous civil wars, a

bloody coup, a volcanic disaster and the Ebola virus, one of the most

pernicious outbreaks of virile infection known to man.

I’d

come to Congo immediately following the American war with Iraq. A war

that I, and hundreds of other journalists, covered with unprecedented

battlefield access. A war that was “hyper” covered in terms

of the amount of perspectives the public was delivered on a daily, hourly

basis. While the statistics are not yet out, it is possible that more

journalists covered the war with Iraq than any other conflict in modern

times. This is not a bad thing, but it begs the question why have some

wars been given an almost celebrity status while others, equally or

more destructive in nature, have hardly registered on the public’s

radar? I like to think it was partly in response to this question that

I was sent to Congo. I’d

come to Congo immediately following the American war with Iraq. A war

that I, and hundreds of other journalists, covered with unprecedented

battlefield access. A war that was “hyper” covered in terms

of the amount of perspectives the public was delivered on a daily, hourly

basis. While the statistics are not yet out, it is possible that more

journalists covered the war with Iraq than any other conflict in modern

times. This is not a bad thing, but it begs the question why have some

wars been given an almost celebrity status while others, equally or

more destructive in nature, have hardly registered on the public’s

radar? I like to think it was partly in response to this question that

I was sent to Congo.

Bunia, the main city in the resource-rich Ituri province,

lies in the northeastern corner of Congo, beside the magnificent Lake

Albert. Financed in part by Uganda and Rwanda, two tribes, the Hema

and the Lendu, have been waging a sustained war over the region in order

to control the riches that lie in the ground. Natural resources, including

diamonds, gold and colton, a material used in cellphones, have been

fueling conflicts in Congo since the 1880’s when King Leopold

II of Belgium commenced the exploitation in a brutal manner.

Working

as a journalist in Bunia is a frustrating experience. Besides the inherent

logistical difficulties, there is the fact that the story, the daily

slaughter of hundreds of Congolese civilians, is mostly happening outside

of our view. Some of the small villages where these massacres occur

are simply inaccessible by road, but most stand surrounded by hostile

militias who will not hesitate to kill any inquiring reporter. This

frustration at not being able to witness and verify events is palpable

at the morning press briefings at the United Nations compound in central

Bunia known by the acronym MONUC. Every morning the small contingent

of journalists gathers around the UN press liaison to hear the daily

tally of dead and missing from Bunia and surrounding environs. If it

is the journalists responsibility to witness, process, and file, than

what is happening in Congo might as well not be happening. For in this

war very little is seen by the outside world, and that which is seems

to draw little attention. It becomes merely sanitized tallies of the

dead and missing read by a UN press officer. Working

as a journalist in Bunia is a frustrating experience. Besides the inherent

logistical difficulties, there is the fact that the story, the daily

slaughter of hundreds of Congolese civilians, is mostly happening outside

of our view. Some of the small villages where these massacres occur

are simply inaccessible by road, but most stand surrounded by hostile

militias who will not hesitate to kill any inquiring reporter. This

frustration at not being able to witness and verify events is palpable

at the morning press briefings at the United Nations compound in central

Bunia known by the acronym MONUC. Every morning the small contingent

of journalists gathers around the UN press liaison to hear the daily

tally of dead and missing from Bunia and surrounding environs. If it

is the journalists responsibility to witness, process, and file, than

what is happening in Congo might as well not be happening. For in this

war very little is seen by the outside world, and that which is seems

to draw little attention. It becomes merely sanitized tallies of the

dead and missing read by a UN press officer.

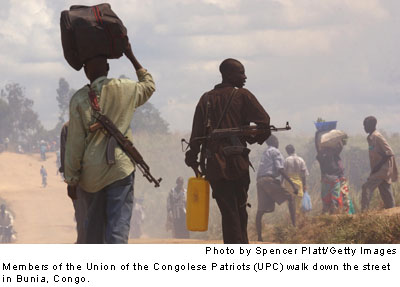

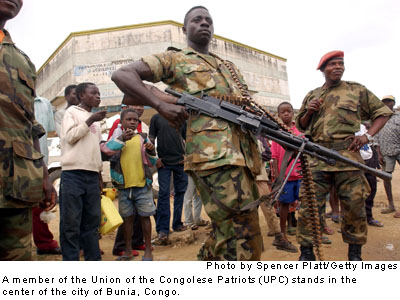

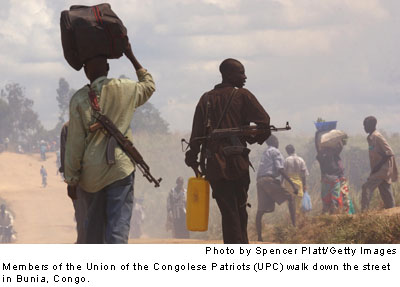

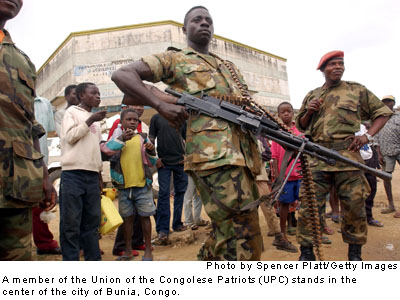

On

Saturday the 7th of June I’m introduced to the state of anarchy

and mayhem that perpetually threatens Congo and seems to erupt without

the slightest warning. After a morning of what sounds like the lumbering

approach of a thunderstorm, the streets of Bunia explode with the distinctive

crackling of gunfire. In what seems like minutes, the Hema controlled

Union of Congolese Patriots (UPC) soldiers, some as young as 10 and

touting AK-47’s as large as themselves, have swarmed onto the

streets of Bunia, wearing looks of drunken fear. Outside of an abandoned

convent where I and a dozen other journalists keep quarters, people

are sprinting with an assortment of household belongings up the rutted

road towards the relative security of the UN compound. A breathless

colleague informs me that the rival Lendu tribe, notorious for their

practice of cannibalism, have commenced a last bid attack on Bunia before

the French peacekeepers are to be fully deployed inside the town. It

appears they are on the edge of Bunia and are making a deft advance.

I proceed up a road towards a group of French photographers who are

searching for two colleagues who went missing earlier in the morning.

At a junction that looks to be a UPC staging area, young soldiers are

being whipped with tree branches for apparently deserting during battle.

With the fighting intensifying, I make a decision that all journalists

grapple with in these situations, when is it time to let go of a story

and seek safety? On

Saturday the 7th of June I’m introduced to the state of anarchy

and mayhem that perpetually threatens Congo and seems to erupt without

the slightest warning. After a morning of what sounds like the lumbering

approach of a thunderstorm, the streets of Bunia explode with the distinctive

crackling of gunfire. In what seems like minutes, the Hema controlled

Union of Congolese Patriots (UPC) soldiers, some as young as 10 and

touting AK-47’s as large as themselves, have swarmed onto the

streets of Bunia, wearing looks of drunken fear. Outside of an abandoned

convent where I and a dozen other journalists keep quarters, people

are sprinting with an assortment of household belongings up the rutted

road towards the relative security of the UN compound. A breathless

colleague informs me that the rival Lendu tribe, notorious for their

practice of cannibalism, have commenced a last bid attack on Bunia before

the French peacekeepers are to be fully deployed inside the town. It

appears they are on the edge of Bunia and are making a deft advance.

I proceed up a road towards a group of French photographers who are

searching for two colleagues who went missing earlier in the morning.

At a junction that looks to be a UPC staging area, young soldiers are

being whipped with tree branches for apparently deserting during battle.

With the fighting intensifying, I make a decision that all journalists

grapple with in these situations, when is it time to let go of a story

and seek safety?

Inside the UN compound journalists join the hundreds

of Congolese refugees who have been living for months inside a makeshift

refugee camp. A bullet ricochets off the compound façade and

we make a dash into the semi protection of the two-story MONUC building.

It is inside this blue and white building where the absurdity of the

situation dawns on me. Crouched amongst us, with expressions that betray

any hint of valor, are the Uruguayan peacekeepers, the original Bunia

force whose mission is to protect the UN compound. Admittedly, these

guys have a tough job. In need of extra income, they’ve volunteered

to come from the relative security of Ur Uruguay to Congo where they

are sitting ducks in one of the most violent and intractable wars known

to man. As the battle on the street begins to subside, a peacekeeper

walks over to a window, gives an indifferent glance outside and then,

sitting down beside me, asks to see if I have any pictures of him in

action.

Waiting

at the airport for my UN flight to take me out of Bunia, I’m approached

by the first chubby Congolese man I’ve ever seen. He carries a

camera and a small tripod under his arm. In broken English he introduces

himself as a member of the Congolese press and asks if I’d like

to see some of the pictures he’s recently taken. The pictures,

5x7 snapshots, are of what appears to be a massacre in a nearby village.

People are strewn about in various stages of decay. Two women hug what

looks to be a child snuggled between them. One man, in a blue t-shirt,

has a crude hole in his stomach, as if someone has purposefully cut

it open in order to take out an organ. I look through them and try to

obtain some of the facts of the scene. My plane arrives and the man

with the tripod and camera takes back his images and walks away. Waiting

at the airport for my UN flight to take me out of Bunia, I’m approached

by the first chubby Congolese man I’ve ever seen. He carries a

camera and a small tripod under his arm. In broken English he introduces

himself as a member of the Congolese press and asks if I’d like

to see some of the pictures he’s recently taken. The pictures,

5x7 snapshots, are of what appears to be a massacre in a nearby village.

People are strewn about in various stages of decay. Two women hug what

looks to be a child snuggled between them. One man, in a blue t-shirt,

has a crude hole in his stomach, as if someone has purposefully cut

it open in order to take out an organ. I look through them and try to

obtain some of the facts of the scene. My plane arrives and the man

with the tripod and camera takes back his images and walks away.

© Spencer Platt

Getty Images

Spencer.Platt@gettyimages.com

Spencer Platt is a staff shooter for Getty Images,

based in New York.

|

I’d

come to Congo immediately following the American war with Iraq. A war

that I, and hundreds of other journalists, covered with unprecedented

battlefield access. A war that was “hyper” covered in terms

of the amount of perspectives the public was delivered on a daily, hourly

basis. While the statistics are not yet out, it is possible that more

journalists covered the war with Iraq than any other conflict in modern

times. This is not a bad thing, but it begs the question why have some

wars been given an almost celebrity status while others, equally or

more destructive in nature, have hardly registered on the public’s

radar? I like to think it was partly in response to this question that

I was sent to Congo.

I’d

come to Congo immediately following the American war with Iraq. A war

that I, and hundreds of other journalists, covered with unprecedented

battlefield access. A war that was “hyper” covered in terms

of the amount of perspectives the public was delivered on a daily, hourly

basis. While the statistics are not yet out, it is possible that more

journalists covered the war with Iraq than any other conflict in modern

times. This is not a bad thing, but it begs the question why have some

wars been given an almost celebrity status while others, equally or

more destructive in nature, have hardly registered on the public’s

radar? I like to think it was partly in response to this question that

I was sent to Congo. Working

as a journalist in Bunia is a frustrating experience. Besides the inherent

logistical difficulties, there is the fact that the story, the daily

slaughter of hundreds of Congolese civilians, is mostly happening outside

of our view. Some of the small villages where these massacres occur

are simply inaccessible by road, but most stand surrounded by hostile

militias who will not hesitate to kill any inquiring reporter. This

frustration at not being able to witness and verify events is palpable

at the morning press briefings at the United Nations compound in central

Bunia known by the acronym MONUC. Every morning the small contingent

of journalists gathers around the UN press liaison to hear the daily

tally of dead and missing from Bunia and surrounding environs. If it

is the journalists responsibility to witness, process, and file, than

what is happening in Congo might as well not be happening. For in this

war very little is seen by the outside world, and that which is seems

to draw little attention. It becomes merely sanitized tallies of the

dead and missing read by a UN press officer.

Working

as a journalist in Bunia is a frustrating experience. Besides the inherent

logistical difficulties, there is the fact that the story, the daily

slaughter of hundreds of Congolese civilians, is mostly happening outside

of our view. Some of the small villages where these massacres occur

are simply inaccessible by road, but most stand surrounded by hostile

militias who will not hesitate to kill any inquiring reporter. This

frustration at not being able to witness and verify events is palpable

at the morning press briefings at the United Nations compound in central

Bunia known by the acronym MONUC. Every morning the small contingent

of journalists gathers around the UN press liaison to hear the daily

tally of dead and missing from Bunia and surrounding environs. If it

is the journalists responsibility to witness, process, and file, than

what is happening in Congo might as well not be happening. For in this

war very little is seen by the outside world, and that which is seems

to draw little attention. It becomes merely sanitized tallies of the

dead and missing read by a UN press officer. On

Saturday the 7th of June I’m introduced to the state of anarchy

and mayhem that perpetually threatens Congo and seems to erupt without

the slightest warning. After a morning of what sounds like the lumbering

approach of a thunderstorm, the streets of Bunia explode with the distinctive

crackling of gunfire. In what seems like minutes, the Hema controlled

Union of Congolese Patriots (UPC) soldiers, some as young as 10 and

touting AK-47’s as large as themselves, have swarmed onto the

streets of Bunia, wearing looks of drunken fear. Outside of an abandoned

convent where I and a dozen other journalists keep quarters, people

are sprinting with an assortment of household belongings up the rutted

road towards the relative security of the UN compound. A breathless

colleague informs me that the rival Lendu tribe, notorious for their

practice of cannibalism, have commenced a last bid attack on Bunia before

the French peacekeepers are to be fully deployed inside the town. It

appears they are on the edge of Bunia and are making a deft advance.

I proceed up a road towards a group of French photographers who are

searching for two colleagues who went missing earlier in the morning.

At a junction that looks to be a UPC staging area, young soldiers are

being whipped with tree branches for apparently deserting during battle.

With the fighting intensifying, I make a decision that all journalists

grapple with in these situations, when is it time to let go of a story

and seek safety?

On

Saturday the 7th of June I’m introduced to the state of anarchy

and mayhem that perpetually threatens Congo and seems to erupt without

the slightest warning. After a morning of what sounds like the lumbering

approach of a thunderstorm, the streets of Bunia explode with the distinctive

crackling of gunfire. In what seems like minutes, the Hema controlled

Union of Congolese Patriots (UPC) soldiers, some as young as 10 and

touting AK-47’s as large as themselves, have swarmed onto the

streets of Bunia, wearing looks of drunken fear. Outside of an abandoned

convent where I and a dozen other journalists keep quarters, people

are sprinting with an assortment of household belongings up the rutted

road towards the relative security of the UN compound. A breathless

colleague informs me that the rival Lendu tribe, notorious for their

practice of cannibalism, have commenced a last bid attack on Bunia before

the French peacekeepers are to be fully deployed inside the town. It

appears they are on the edge of Bunia and are making a deft advance.

I proceed up a road towards a group of French photographers who are

searching for two colleagues who went missing earlier in the morning.

At a junction that looks to be a UPC staging area, young soldiers are

being whipped with tree branches for apparently deserting during battle.

With the fighting intensifying, I make a decision that all journalists

grapple with in these situations, when is it time to let go of a story

and seek safety?  Waiting

at the airport for my UN flight to take me out of Bunia, I’m approached

by the first chubby Congolese man I’ve ever seen. He carries a

camera and a small tripod under his arm. In broken English he introduces

himself as a member of the Congolese press and asks if I’d like

to see some of the pictures he’s recently taken. The pictures,

5x7 snapshots, are of what appears to be a massacre in a nearby village.

People are strewn about in various stages of decay. Two women hug what

looks to be a child snuggled between them. One man, in a blue t-shirt,

has a crude hole in his stomach, as if someone has purposefully cut

it open in order to take out an organ. I look through them and try to

obtain some of the facts of the scene. My plane arrives and the man

with the tripod and camera takes back his images and walks away.

Waiting

at the airport for my UN flight to take me out of Bunia, I’m approached

by the first chubby Congolese man I’ve ever seen. He carries a

camera and a small tripod under his arm. In broken English he introduces

himself as a member of the Congolese press and asks if I’d like

to see some of the pictures he’s recently taken. The pictures,

5x7 snapshots, are of what appears to be a massacre in a nearby village.

People are strewn about in various stages of decay. Two women hug what

looks to be a child snuggled between them. One man, in a blue t-shirt,

has a crude hole in his stomach, as if someone has purposefully cut

it open in order to take out an organ. I look through them and try to

obtain some of the facts of the scene. My plane arrives and the man

with the tripod and camera takes back his images and walks away.