In 1999, the first Platypus Workshop was designed by Dirck Halstead to train a group of photographers in video storytelling. Newspapers, magazines, broadcasters and cable networks would need more and cheaper news and documentary content. Thousands of websites capable of streaming video, would open a huge market for the Platypus, a journalist who could tell a story with video or stills. Uniquely adapted to its own individuality, the Plat walked like a duck and quacked like a duck. It shunned many of the newsgathering conventions and techniques used by television news mammals. Although three workshops were held in conjunction with the NPPA in Norman, Oklahoma, the Platypus was meant to be an auteur, not stuck with a cumbersome team and expensive equipment like its tv news cousins, once removed. A workshop highlight of Plat 2001 was PF Bentley's stand-up discourse on traveling light. The idea was to pack everything you need in an itty-bitty bag, and go shoot your story, while network television crews were stuck like octopi trying to get through a revolving door.

There they discussed technologies and markets that developed in a parallel universe called "reality programming" which often uses small format cameras, and "one man band" shooters. They also learned about movie making and HDTV produced on digital video. The Advanced Workshop provided inspiration and instruction for Platypii with bigger ambitions for bigger productions for bigger audiences. The curriculum included instruction in pre-production, legal issues and releases for documentaries, blow-ups to 35mm theatrical release, and Academy consideration. Panasonic rep Greg Boren demonstrated the SDX900 video camera, capable of shooting feature motion pictures for theatrical distribution. For a ballpark figure of 25K for the camera, 15K for the recorder, and anywhere from 10-20K for the lens, the platypus can come full circle and jump into big team big budget story telling. Although some workshop participants doubt they will ever "go Hollywood," they've been exposed to the resources they'd need, if they did. "Among many things that I took away from the workshop is that the filmmaker pick the right tool for the job," wrote Advanced Plat participant Jim Sugar. Knowing how it's done on a full budget never hurt the one-man-band videomaker. When the Plats discovered that the bigger cameras balance better on the shoulder, did they wonder whether their Road Less Traveled might in fact merge somewhere onto the Hollywood Freeway? Guest speaker Richard Propper, President of Solid Entertainment,

a documentary distributor specializing in foreign markets, described

the advantages of co-production over acquisition, and shared a list

of contacts where Platypii might market their work. His company is regularly

contacted by programmers at networks like SKY TV, who might, for example,

plan a series of programs on a topic like "sharks" and buy

single-use rights to broadcast available documentaries. There might

be a market for nature shows, or a three-day tribute series to Elvis

Presley. Propper said his catalog filled this sort of need, with a list

that includes one title called "Shmelvis: The Jewish Elvis."

You can't market something like that by yourself, concludes an alert

Platypus, but a foreign distributor might. Chuck Braverman supplemented

with a list of contact numbers of domestic programmers. When he finally received permission to interview Elaine Friedman, the wife and mother of the accused (and mother of David Friedman, the party clown) they set up in a front room of her home. "I don't feel comfortable here," she told them, "I don’t look like myself." She asked them to set up all over again in the dining room. This accomplished, she asked to move again, to another room, deeper in the house. Finally, on the third setup, she began her first of two interviews for the documentary. At this point Jarecki was still unaware of the family drama twenty years earlier. "We were a family," Elaine began. The revelations that followed, that there was "a secret story," and that there existed not only a huge box of 8mm family film but another 25 hours of home video shot following the arrests, convinced Jarecki that his documentary would be the Friedman family story. The film he made was a result of patience, perseverance, and his ability to listen, without interrupting, as different people told their stories. Jarecki credited his editor and crew for their contributions, adding that he was able to pay their salaries from the fortune he earned from the sale of Moviefone, the internet movie guide and ticket service. He described his editorial technique by saying, "the audience needed to be given its own space to make its own decision about what happened." Jarecki's insights and obvious satisfaction with his life as a documentarist, inspired the class to dream big. Although the workshop emphasized grand ambition, there were some practical presentations as well, including a half-day clinic on Final Cut Pro 4, the edit system used by most independent video documentarists. Some Platypii commented they would have liked additional instruction in lighting, microphone placement, cinematography and production techniques. All seemed inspired to continue their efforts, great and small. We'll know someone made it when we hear, "Thank you. thank you very much. Members of the Academy, it all started many years ago with a little 1-chip camera."

© AMY BOWERS |

|

|

Write a Letter

to the Editor |

Y

Y Platypus

graduates, like Freemasons, live quietly in our communities, working

their day jobs and taking their twins to soccer tournaments. Some create

videos for their publications. Others make CDs or DVDs for corporate

clients or nonprofits. Many find funding through state agencies, individuals

or grants. A sizeable handful produce and shoot stories for broadcast

television. They improve their skills and refine their goals alone,

or in small groups that communicate on list-servs and user groups. Some,

ready for help with the next step, enrolled in the July 2003 Advanced

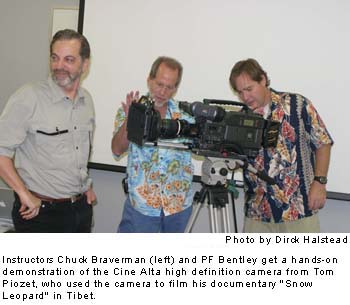

Platypus Workshop, taught by Dirck Halstead, television producer Chuck

Braverman, PF Bentley, now of Brooks Institute, and Jim McNay, also

from Brooks, the campus lit by beach sun in Ventura, California.

Platypus

graduates, like Freemasons, live quietly in our communities, working

their day jobs and taking their twins to soccer tournaments. Some create

videos for their publications. Others make CDs or DVDs for corporate

clients or nonprofits. Many find funding through state agencies, individuals

or grants. A sizeable handful produce and shoot stories for broadcast

television. They improve their skills and refine their goals alone,

or in small groups that communicate on list-servs and user groups. Some,

ready for help with the next step, enrolled in the July 2003 Advanced

Platypus Workshop, taught by Dirck Halstead, television producer Chuck

Braverman, PF Bentley, now of Brooks Institute, and Jim McNay, also

from Brooks, the campus lit by beach sun in Ventura, California. "Nobody

wants to die without telling their story," said Andrew Jarecki,

quoting Al Maysles, a forefather (with his brother David Maysles) of

documentary film, to a full house at Brooks Institute, following a screening

of his feature documentary "Capturing the Friedmans." Jarecki,

a novice filmmaker, described how his movie, which he originally started

as a portrait of party clowns in Manhattan, evolved into a program about

a Long Island family that was torn apart in the 1980's when the father

and one of the sons was arrested for child molestation.

"Nobody

wants to die without telling their story," said Andrew Jarecki,

quoting Al Maysles, a forefather (with his brother David Maysles) of

documentary film, to a full house at Brooks Institute, following a screening

of his feature documentary "Capturing the Friedmans." Jarecki,

a novice filmmaker, described how his movie, which he originally started

as a portrait of party clowns in Manhattan, evolved into a program about

a Long Island family that was torn apart in the 1980's when the father

and one of the sons was arrested for child molestation.