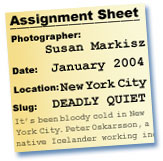

DEADLY QUIET

By Susan B. Markisz

It’s been bloody cold in New York City. Peter Oskarsson,

a native Icelander working in New York, was quoted in a January

26, 2004 New York Times story on the arctic temperatures, saying: “I’ve

never in my life been as cold as I have been in New York.” Though

I’ve never been to Iceland, I’ve had to cover a number

of outdoor assignments in New York City, and I have to concur

with Oskarsson. Sadly, the frigid temperatures have contributed

to several deaths throughout the metropolitan area, all of which

were preventable.

One can only imagine what it must be like to have your heat turned

off by Con Edison because – perhaps you’ve been laid

off – and you can’t pay your heating bill, as the

temperature plummets to the single digits, and stays there for

4 solid weeks. Or the landlord doesn’t provide enough heat

to keep your kids warm and toasty so you rely instead on – unbeknownst

to you - a faulty heater, which emits a tasteless, odorless gas

and silently kills all members of your family. In one of the

houses where carbon monoxide poisoning was responsible for two

recent deaths, the meter brought in by the fire department registered

500 parts per million; even 30 parts per million over a prolonged

period of time can be dangerous. One can only imagine.

Covering cold weather tragedies presents special physical challenges

in trying to keep warm and the extremities from becoming numb.

But even more challenging are the obstacles we sometimes encounter

at crime scenes. In New York at least, photographers have been

on the defensive since September 11 and are often at the mercy

of the authorities at the scene to get access. In this space,

I won’t delve into all of the First Amendment and civil

liberties issues, which have surfaced in recent years for photographers

trying to get access; that’s a story – a long one

- for another day.

On a much more fundamental level, however, is the fact that photographers’ relationships

with the police department and other authorities whose discretion

we must rely on to cover breaking news, suffer from a PR image

problem.

Antagonism

between the NYPD and the newsroom has escalated since the terrorist

attacks with the apparent perception that we are akin to news “paparazzi.”

| I

think we’re a pretty well intentioned group, with

the objective to be able to convey a sense of what happened,

or the effects of a tragedy on its victims and survivors.

Perhaps the photograph we take might motivate people to

heed warnings about, say, the dangers of carbon monoxide

poisoning, or whatever it is that has brought us to this

location in the first place. |

| Theresa

Connolly reacts to the news that two of her neighbors,

a father and daughter died of carbon

monoxide poisoning in the Woodlawn section of the

Bronx on January 13, 2004.

© 2004

Susan B. Markisz for The New York Times.

|

|

Battalion

Chief Dennis Munnelly spoke to the press after 6

victims were taken to area hospitals from a

private home at 4279 Oneida Avenue in the Woodlawn

section of the Bronx. Shortly after 7:30 pm, two of

the victims were reported to have died and 2 others

remained in critical condition. Chief Munnelly advised

neighbors to purchase carbon monoxide detectors.

© 2004

Susan B. Markisz for The New York Times. |

|

As

I arrived on a scene in November where a family of three

had died of carbon monoxide poisoning, most of the EMS

vehicles had already gone away empty, leaving only a few

police officers guarding the street, a couple |

of

bystanders, and Con-Ed workers and FDNY inspectors going in

and out of the house - windows wide open - waiting for the

coroner to appear.

Local

newscasters were set up with their satellite trucks down

the block waiting to do their 11 PM live shot. After shooting

from my limited perspective, I asked a plainclothes

detective to allow me to cross the street, which was cordoned

off

by yellow tape. He shouted “No,” and when I added

a second plaintive “Please,” he shouted “NO” even

louder the second time. When I asked why, he turned his

back to me and wouldn’t even acknowledge my presence.

A walk around the block to get to the other side of the scene

would

have taken at least 10 minutes, because of the bizarre

street

pattern and the manner in which the police had cordoned

off the scene. If I had been a resident on the street where

the

tragedy

occurred, I would have been allowed to cross the approximately

30 feet to the other side. As a press photographer I was

not. Fortunately,

a uniformed officer, having witnessed his superior’s

response, came over and told me he would escort me

across the street in

a few minutes, and he did so when the detective walked

away.

The other side of the street didn’t provide much more of

a picture. There were no victims’ families on the scene

and the coroner’s van had not yet arrived; the Metro deadline

was quickly approaching and I had little to show for my efforts.

I knew that the picture didn’t have to shout “dead.” Still,

I didn’t have much and it was 11pm.

I

noticed that a man on the second floor of an apartment

house adjacent to the house where the victims had died,

peered out the window periodically at the going’s

on in the street.

Except for the well-lit porch of the house where investigators were searching

for evidence, it was eerily quiet, and pretty dark outside. |

New

York City Fire Department Investigators survey the

scene at a private home at 1708 Popham Avenue & 176th

Street in the Bronx where three people succumbed to

carbon monoxide poisoning from a generator which malfunctioned.

There was no heat in the house.

© 2003 Susan B.

Markisz |

|

Nevertheless,

I began shooting the silhouetted guy in the window. A good

friend and fellow photographer

standing next to me, realizing my flash wasn’t going off,

looked at me astonished and asked: “You mean you’re

shooting available light???” I said, “Yep, 1600,

tungsten white balance. Take a look at that guy in the window.

It’s

not a very literal picture, but unless something dramatic

happens in the next 10 minutes, that’s my shot.”

To my surprise, he started shooting without his flash, and

then after a few frames, turned his flash back on, laughed

and said: “Fugheddaboudit...my

paper will never go for this.”

I was risking my deadline by staying any longer, and I started

to leave when suddenly, the man I had been photographing,

reappeared at the window, this time with an infant in

his arms. I shot 2

or 3 frames and left. As soon as the editor saw the first

picture I transmitted, he called to tell me that was

the picture. In

a case where, tragically, an infant had died in the house,

he said, it made the photograph with the guy with the

infant in

his arms silhouetted in the window of the building next

door, a quiet and moving shot.

An

oxygen mask left in front of 4279 Oneida Avenue in

the Woodlawn section of the Bronx by EMS workers

on January 13, 2004 when members of a family were overcome

by carbon monoxide poisoning, claiming the lives of

two victims, left an eerie reminder of the dangers

of carbon monoxide poisoning. January 14, 2004.

© 2004

Susan B. Markisz for The New York Times. |

|

In

a carbon monoxide poisoning 2 weeks ago that left a father

and daughter dead, and the mother and son in critical condition,

the only way to convey the sense of tragedy was to photograph

the neighbors’ reactions and the oxygen masks that

EMS workers had left lying on the street and shrubbery

around the house. |

On

January 13, 2004, carbon monoxide poisoning claimed

the lives of a father and daughter on Oneida Avenue

in the Woodlawn section of the Bronx, leaving the mother

and son in critical condition. A neighbor, Walter Sammon,

who lives across the street from the Duffy family,

went out and purchased a Carbon Monoxide/Smoke Detector

this morning from Sears for about $50. January 14,

2004.

© 2004 Susan B. Markisz for The New York

Times. |

|

The

next day, although this picture was not used in the follow-up

story, we encountered a neighbor on the street who had

gone out to purchase a carbon monoxide detector for his

home. |

Authorities

who believe they have a right to prevent these stories from

being told because either they feel it’s

their duty to protect the public from the media, for

their own personal

reasons, should know that besides the fact that it

is not their job, in this case, at least one person was

motivated to go out

and buy a carbon monoxide detector the following day.

In all likelihood, neighbors in the immediate vicinity

would have learned

soon enough about the tragedy. But without media coverage,

it would have been just another neighborhood tragedy,

known only

to a few neighbors and passers-by. Without the media,

there would have been no microphone or reporters to record

the fire chief’s

appeal to the public to purchase carbon monoxide detectors

for their homes. Without the media, it would have been

just another

quiet night in the neighborhood. Deadly quiet.

© 2004 Susan B. Markisz

January 31, 2004

Smarkisz@aol.com