|

→ June 2004 Contents → Commentary

|

| |

How One Photographer Saved History

June 2004

|

|||

|

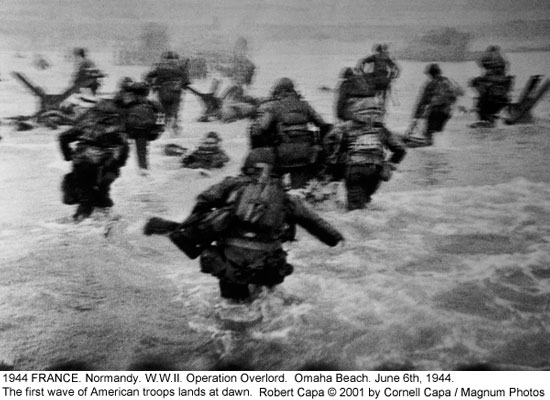

LIFE photographer Robert Capa was not the only cameraman on the bloody beaches of Normandy on June 6th 1944.

There were others, some of them military, some members of the wartime pool, and they shot both stills and movies. Some were killed or wounded. We will never know for sure how many, or how many photographs or feet of film they shot. That is because,other than an early photo by AP photographer Bert Brandt and some pictures that showed up later from an unknown Coast Guard photographer, only eleven frames from one damaged roll survived that first day on Omaha Beach.

John Morris recounts in his feature article this month the behind-the-scenes story of Capa's famous roll with the exposures that have become icons documenting the greatest invasion in the history of the world.

So, what happened to the other images?

Capa, meanwhile, who had managed to make it to the beach in the first wave of troops, was now totally shaken. After exposing 4 rolls of 35mm, he clambered aboard a returning landing craft, and made his way back to England where he handed off the film to a courier and then returned to France. Despite most of his film being ruined in the LIFE offices in London, the eleven images that survived are some of the most powerful in the history of photojournalism.

Today, we are accustomed to ubiquitous news coverage. When U.S. Marines went ashore in Somalia, they were greeted not by hostile fire but ranks of cameramen who had been positioned in anticipation of their arrival. The volume of photographs covering the Abu Grahib prison abuses last month led us to assume that the soldiers guarding the prisoners had organized one big camera club. Pictures flood publications capturing nearly every event. They rain down in a blizzard of megabytes.

Yet there have been times when our history has rested in the hands of one individual photographer. This was the case on Omaha beach. In the end, if it had not been for Capa's bravery and commitment there would be no visual record of this turning point in history. Veterans of that bloody morning would have told their stories and drawn verbal pictures, but there would have been no visual evidence. Nothing would have remained for Steven Spielberg to refer to in recreating the chaos of that day in his movie "Saving Private Ryan."

It is a reminder of the responsibility and the power of the individual photojournalist.

© Dirck Halstead

|

|||

Back to June 2004 Contents |

|