PROLOGUE

I was twelve years old when the radio announced that the Allies had

launched the long awaited invasion of Europe that would ultimately

lead to victory and the end of World War II. That day was June 6,

1944 and would come to be known as D-Day.

This June will be the 60th anniversary of that historic event.

I beg your indulgence as I begin the story, about one of the greatest

assignments of my long career as a newspaper photographer.

D-DAY REVISITED

By Dick Kraus

Newsday

Staff Photographer (retired)

CHAPTER THREE

The next

morning found us boarding an express train that would take us through

some of the loveliest European countryside. The train was fast

and comfortable and Kindall and I kind of dozed our way through

the hours, watching picturesque medieval cities, towns and villages

flash past our large window. The train stopped briefly at the French-German

border where we were asked to show passports and travel documents

to the border guards who walked through the train. The landscape

flattened as we sped through the French farmland. In November,

daylight wanes rapidly by three PM in those latitudes. It was dark

by the time we pulled in Caen. We gathered our bags and detrained.

The first thing that we needed to do was rent a car and then go

find a hotel. Well, we found a car rental office right across the

street from the station. We also found that it was closed; not

only for the night, but also for the weekend. It was Saturday and

they wouldn’t open again until Monday. We were supposed to

begin photographing the invasion beaches, the next day. Plus, we

were supposed to meet our German machine gunner, Franz Gockel,

at the American Cemetery in Coleville.

We went back to the station and sat on a bench while we surveyed

our options. We asked a cab driver how much it would cost to take

us to Coleville, the next day. He quoted us a price in francs which

we felt to be pretty expensive. It didn’t matter, though.

We would have paid it except that neither of us had enough francs

to

make the trip. We were still carrying a bunch of German marks,

thinking that we would get a better rate of exchange when we got

to France.

Dumb move. Our next option was to inquire of the man at the ticket

window, if there were trains to Coleville the next day. Fortunately,

there were and we could use our Eurail pass. But, we would have

to take a cab from there to the American Cemetery to meet Gockel.

We

would have just enough francs to make it.

That

having been decided, our next priority was a hotel. Preferably

someplace we could stay for the week and use as a base of

operations. In order to conserve our meager stash of francs,

we opted to walk the couple of miles from the station, to

the outskirts of the city of Caen. I hefted that heavy monster

of a duffel bag onto my shoulder and we proceeded. Aided

by the large maps of the city, mounted on lamp posts every

few blocks, we finally crossed the bridge over the River

Orne and the two of us, tired and bedraggled, entered the

city. From the bridge, I had noticed what appeared to be

a hotel. OK. So the building was outlined in yellow fluorescent

lights and a sign in lights spelled out “Hotel Courtonne.”

I didn’t think that I could take another step with that monster bag on

my shoulder. I even gave it a name. I called it “Monster Bag.”

“ Jim,” I said, “that’s gonna be our headquarters.”

|

© Newsday photo by

Dick Kraus

The Hotel Courtonne at left. |

|

The desk

clerk didn’t speak much English and my high school

French deteriorates as I tire. And, I was tiring fast. But,

we managed to book a couple of rooms for the week.

The place turned out to be an old third class hotel with

tiny rooms. But, our newspaper would be pleased with the

economy

of the place.

It was clean and convenient and anyway, we wouldn’t

be spending much time in the rooms, since we would be ranging

out over the countryside

each day, in pursuit of our stories.

We dumped our bags, washed up and headed out for some dinner.

After walking several blocks, we happened upon a quaint

cobblestone square

that was lined with some interesting restaurants. We

walked around, looking over the menus and prices. Most were

pretty

upscale.

But, what the Hell. We deserved to have a good meal and

we were on expenses.

Besides, look at the money that we were saving the paper

with our hotel.

It was almost 10 PM and I wondered if the restaurants

stayed open that late. I was soon to discover that

Europeans dine

very late.

Most of the restaurants, we were to find, didn’t

even begin to serve dinner before seven or eight PM

and stayed open until well

past midnight.

There were two Moroccan restaurants on the square and

Jim thought one of them would be a good place to

start. He

had never had

Moroccan cuisine. I, on the other hand, was very

familiar with Moroccan

food. My wife, at the time, was from Morocco. She

was an excellent cook

and I knew my way around cous cous with lamb or chicken,

along with any number of other Middle Eastern dishes.

We sat down to enjoy a very tasty meal and then went

back to the hotel to pass out in utter exhaustion.

I was awakened

in

the wee

hours of the morning with terrible stomach cramps.

My exotic Moroccan meal had turned my insides into

a painful,

churning

liquid mess

and I spent several hours on the commode trying

to rid myself of whatever

was causing me such discomfort. I had the runs

for the next few days until one night, when I was on

the phone

to my wife,

I told

her of

my malady. She told me to drink some boiled milk.

Jeez. I remember my mother giving me that whenever

I had

stomach problems as

a child. I hated the taste but it was effective.

The next morning at breakfast

in the hotel, I asked the waiter for boiled milk.

At least that’s

what I thought I was asking for when I requested “latte brouille,

s’il vous plait.” As I said before,

my French leaves a lot to be desired. The waiter

looked at me like I had two heads.

I guess that no one in France asks for their milk

to be scrambled. Eggs, maybe. But not milk. I was

to have these kinds of language

problems all through France. But, I managed to

make my request understood and I got the boiled

milk. By afternoon, my problem was gone.

Anyway, the

morning after the fateful Moroccan meal, with my stomach threatening

to embarrass me at any moment, we hiked back to the railroad station,

traveled to Coleville, took a cab to the American Cemetery and

checked in with the American superintendent of the place

© Newsday Photo by Dick Kraus

Crosses and Stars of David

mark the resting place of thousands of American GI's

at the American Cemetery at Coleville in Normandy. |

|

We were

given a brief history of the cemetery and taken on a tour.

In the weak sunlight of a winter day,

we saw row upon row upon row of simple headstones, marked with

crosses and an occasional Star of David that covered the gentle

rolling ground that was situated on a high cliff that overlooked

the beachhead that was Omaha Beach. |

I took

a few photographs before we were met by Franz Gockel and

his wife. They had driven by car to Normandy from their home

in Germany. We walked outside the gates of the American Cemetery

and Gockel led us across the cliff for another hundred yards

or so. There he pointed out a ditch that had once been a

trench. Carved out of the side of that trench was a dugout,

lined with stones and just discernible through the tangled

growth that had sprung up over the intervening decades. It

offered a clear view of the beach, just below, and Gockel

pointed out that this was his machine gun nest from which

he fired upon the thousands of American GI’s who swarmed

off their landing craft. At least, those who made it past

the shells and the deep water and sandbars offshore. |

© Newsday Photo by Dick Kraus

Franz Gockel stands near

the remains of his machine gun nest from where he fought

the Allies on D-Day in 1944. |

|

© Newsday Photo by Dick Kraus

Franz Gockel looks at a cross

that he had erected near his machine gun nest, as a

memorial to his fallen comerads. |

|

As Gockel

stood there, remembering the events of 1944, I made photographs

of him from every conceivable angle. These would be better

images and much more relevant than any of the head shots that

I had made of him back at his home. It seemed to me at the

time, looking at the old German veteran, that he was hearing

the sounds of battle and smelling the gunpowder from his gun

as he stood there and relived that cataclysmic day. |

We walked

back to the cemetery parking lot and Franz drove us a few miles

away to

a small, privately

owned

and operated

D-Day

Museum.

It was run by a local farmer who had collected

many artifacts of that battle and had constructed

a small

museum with

dioramas depicting

the scenes of war. Gockel had gotten to

know this Frenchman and his

family and they had become friends. We

were introduced and Kindall interviewed the farmer

and his family,

getting the

perspective

of the French citizens who lived through

those dramatic times. The farmer

had included a diorama of Gockel’s

machine gun nest and there was a wax mannequin

of a German soldier manning a heavy caliber

machine

gun that was supposed to be Gockel.

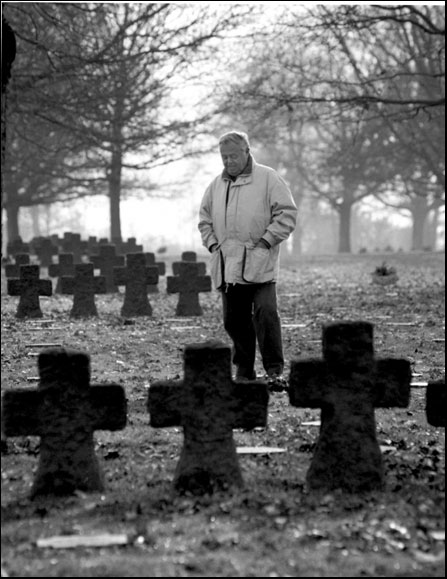

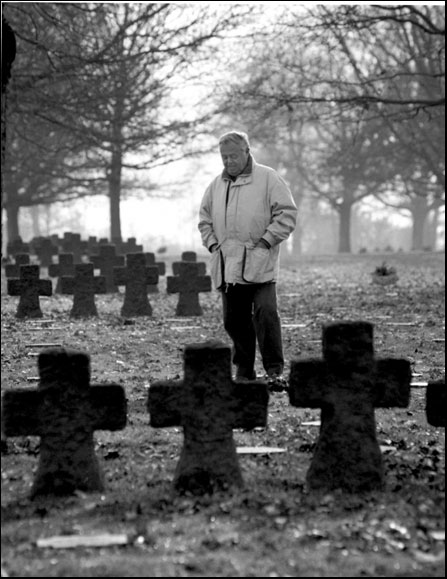

From

there, we drove further inland to the German military cemetery,

Soldatefriedof, in La Cambe. This is the focus of Gockel’s

yearly pilgrimages to Normandy. It is here that his friends

and comrades in arms lay buried. It is here that he comes to

pay his respects and to lay flowers on graves of those he once

knew.

Here, instead of the simple head markers that we saw at the American Military

Cemetery, massive Teutonic Crosses stand at the heads of groups of graves.

It is a very imposing sight and it made for some very impressive photos.

When we came to a group of graves that marked the final resting place of

some of his comrades, Franz laid flowers at their feet and bent to one

knee to offer a prayer. |

| © Newsday Photo

by Dick Kraus |

|

I tried to keep a respectful distance

so as not to intrude. With long lenses

and

shallow depth

of field,

every angle

from which

I shot made very dramatic pictures.

Still, I knew there was one that

was missing. One that showed the solemnity

of the occasion. I walked around to

the back of

those

large crosses

and I saw, instantly,

what I must do. I didn’t need recognizable photos showing Franz’s

face. I needed a picture that showed an old German soldier; once

an enemy, now just another survivor of a long past war, remembering

his dead friends, just as many American GI’s

were doing at the American cemetery

up the road.

I snapped on my 14mm, ultra wide-angle lens and laid the camera

on the grass. I couldn’t see what I was getting through the

viewfinder. Older versions of the Nikon had removable prisms which,

when removed, allowed you to sight down into the ground glass viewing

screen. Lacking that ability, I could only place the camera where

I estimated the angle that I desired and I shot several frames,

changing the angle slightly each time.

| © Newsday Photo by Dick Kraus |

|

Oh, what I

would have given to have had a digital camera back then. I could have reviewed

my shots on the back screen and made whatever adjustments that were necessary.

It would be another week before I would be back at the paper, developing

my film, before I could see the results. Fortunately, years of experience

had served me well, and I did get what I wanted. And it is one of my most

treasured shots. |

Jim and I

took the Gockels to a lovely restaurant in the countryside for

a delightful dinner.

Thankfully, American

Express was accepted,

because we hadn’t a sou

in French money to our name.

Then

Franz drove us to the railroad

station for our trip back to Caen

As

soon as we got off the train in Caen, we went to the car rental

agency and rented a small Renault. It had a five speed manual

tranny and no power, so I was more than happy to let Kindall

do the driving. And, we also managed to change our money to

francs. Now we were all set. We drove back to the hotel and

parked on the street, as there was no hotel parking.

We had a lot to cover the next day, so we were up early. Our

first stop was at Le Memorial at Caen. This was an extensive

museum devoted to the D-Day landings, located in a modern building

and run as a joint venture by the French and Americans. Kindall

had been in touch with them by mail and by phone and had made

contact with a young American woman who was the Special Events

Coordinator. She was most helpful and showed us around the various

exhibits in the museum. There were so many wonderful displays,

from a large scale diorama showing model landing craft coming

ashore on the beaches and the opposition forces arrayed against

them, to cutaways of a B-17 Flying Fortress heavy bomber. I had

my work cut out for me, trying to decide which things to photograph

and which to omit. There was just so much that it became overwhelming

and I knew that I’d be lucky if one or two of these made

the final cut in the paper.

After a few hours, we hit the road and Kindall maneuvered our

little car through the city traffic and out into the Norman countryside,

on our way to look over the landing zone at Utah Beach. The roads

were narrow and the countryside was beautiful as we headed north. |

|

|

© Newsday Photos by Dick Kraus

Views of Le Memorial in Caen.

|

|

As we approached the shore,

there were areas that still displayed the fury of the allied landings

in 1944. There were stretches of real estate just inland from the

beach where the German Army had constructed fortifications and

pillboxes of thick, re-enforced concrete. Many of these were still

in evidence; some blasted apart by high explosive ordinance from

allied ships and planes. The surrounding area was pocked with huge

craters and the landscape resembled the surface of the moon.

© Newsday Photo by Dick Kraus

French Schoolchildren climb

over the blasted remains of German fortifications that

failed to fend off the Allied troops coming ashore

at Pte. Du Hoc on the Normandy coast. |

|

Many of the pillboxes

still contained the large coastal guns that had once wreaked havoc

upon the ships and landing craft. I was amazed at how well those

weapons had withstood the corrosive power of the dampness and the

salt laden air along the seacoast. I climbed around those bunkers

and over the cannon and to my eye, it looked as though the guns

were still operable. Even though there had been no maintenance

performed on them for fifty years, you might possibly load them

with powder and shell and fire them off, probably to the detriment

of the French and English fishing fleets that still ply their trade

in those waters. There were signs in several languages, warning

of unexploded shells, still buried in the sand where they have

lain for all these years.

© Newsday Photo by Dick Kraus

One of the German coastal

guns that escaped the Allied bombardment on D-Day, still

stands, guarding the Normandy coastline at Longues

sur Mer. |

|

© Newsday Photo by Dick Kraus

Inside the German gun emplacement at Longues sur Mer, The

coastal gun stands as it did 50 years ago on D-Day,

without a hint of deterioration.

|

|

© Newsday Photo by Dick Kraus

Newsday writer Jim Kindall looks across the water at the

high, steep cliffs of Pte. Du Hoc where Len Lomell

and his fellow Rangers scaled to the top on D-Day. |

|

On a

high promontory, overlooking the English Channel, was Pte.

Du Hoc, This is where the American Rangers scaled the cliffs

to eliminate those German 155 mm coastal guns about which we

were told when we interviewed Len Lomell back in New Jersey

a few weeks ago. Hearing him narrate the story of those brave

GI’s hauling themselves up the ropes along the vertical

face of those stone cliffs under withering small arms fire

was dramatic enough. But seeing those imposing sheer walls

in person brought the immensity of the task into perspective

and as I photographed the area, I had a sudden sense of humility

in the knowledge of the bravery of those gallant men. |

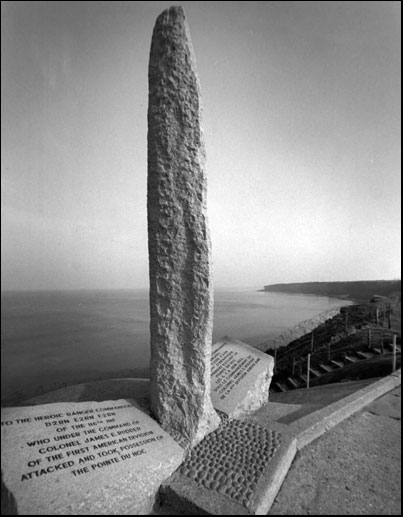

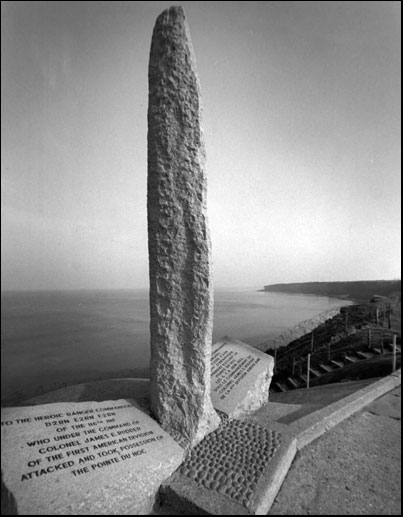

| There

are many memorials all over Normandy, dedicated to different

units who fought on D-Day and the days following. None is more

imposing than the rather phallic looking concrete obelisk that

rises above the spot where the battle took place at Pte. Du

Hoc. |

© Newsday Photo by Dick Kraus

The Memorial atop of Pte. Du Hoc, dedicated to the American

Rangers who scaled the cliffs and fought and died on

D-Day. |

|

In contrast to

the noise and

death that occurred

there

in June of

1944,

on this winter day

in 1993,

there was a stillness

and serenity

that

seemed oddly out of place, given the

nature

of our assignment. In

the fading

light

of a winter day,

trainers

from

a nearby racetrack

were working out their horses

and sulkies

on the

hard packed sand.

Long gone were

the tracks

of tanks and amphibious

vehicles

and the boot prints of

soldiers.

And, the

bloodstains

in the sand.

© Newsday Photo by Dick Kraus

Trainers from a nearby race track, work out their trotters

on the hard packed sand of what had been Utah Beach. |

|

CHAPTER FOUR COMING NEXT MONTH

newspix@optonline.net

http://www.newsday.com

|