PROLOGUE

I was twelve years old when the radio announced that the Allies had

launched the long awaited invasion of Europe that would ultimately

lead to victory and the end of World War II. That day was June 6,

1944 and would come to be known as D-Day.

This June will be the 60th anniversary of that historic event.

I beg your indulgence as I begin the story, about one of the greatest

assignments of my long career as a newspaper photographer.

D-DAY REVISITED

By Dick Kraus

Newsday

Staff Photographer (retired)

CHAPTER FOUR

© Newsday Photo by Dick Kraus

A dusting of snow coats the ground at the German fortifications

and shore batteries at Longues sur Mer.

|

|

For the

next few days, Jim Kindall and I traveled up and down the coast

of Normandy in our rented car, trying to capture the the ghosts

and memories of that D-Day in 1944. As we walked along the

peaceful, hard packed sand of Omaha and Utah Beaches, we tried

to imagine what it must have been like almost 50 years ago.

It was now November and the cold wind blew in off the English

Channel and the light grew weak by early afternoon. It was

next to impossible to photograph anything that might resemble

what happened on that “Longest” summer day in ‘94. |

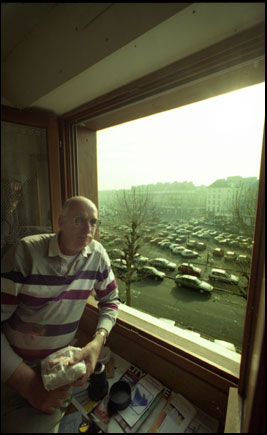

| I shot

frame after frame of anything that was left of the battles

and we would return to our hotel, long after dark, tired and

hungry. I would be bringing my unexposed film back to the paper

to be processed, but I spent long hours, each night, checking

my caption notes to make sure that I had all of the information

that I would need. Kindall did the same with his notes and

we would compare information and spellings to make certain

that both of our stories jibed. |

© Photo by Dick Kraus

(self timer)

I sit in the window of my hotel room, going over

caption information.

|

|

© Newsday Photo by Dick

Kraus

A souvenir stand sells D-Day memorabilia at Omaha Beach. |

|

© Newsday Photo by Dick Kraus

A rusting hulk of a landing craft still sits on the sand

at Utah Beach. |

|

© Newsday Photo by Dick Kraus

Mile markers set up by the advancing Americans show the

slow and costly route inland from Utah Beach.

|

|

All

of our efforts on this trip were to be used in a special

edition about

D-Day that would run in the Sunday paper on the weekend before

June 6th, 1994; the actual 50th Anniversary of the invasion.

Kindall and I wouldn’t be there to see the results of our

work until later. We were going to be back in Normandy, a week

before June

6th, to cover the

special events that would take place to commemorate the invasion.

And those stories and photos would be filed and transmitted back

to our paper to be used on a daily basis.

But, for now, the story was just taking shape in Kindall’s

mind. Over late dinners, we would talk about what we did each

day and I would try to recall the photos that I had taken to

determine

which ones might be more relevant. Each day we would place a

call to our desks, just to touch base and let them know how the

story

was progressing.

I had arranged with the proprietors of our little hotel, to reserve

two rooms for us when we came back. We had learned that lodging

was almost non-existent in Caen or anywhere in Normandy for the

duration

of the D-Day Anniversary. Huge numbers of American veterans and

their allies would be flocking here for these ceremonies. Plus

there were

government and military officials and heads of state from the

allied countries, and their entourages and security who would

need accommodations.

Throw in a tremendous media presence and you had a huge demand

for every available nook and cranny. Our hotel hosts assured

us that

they would hold two rooms for us for the two weeks that we would

be back in Caen.

One night, we got back to the hotel earlier than usual and I

scoured the neighborhood to try to find a place where I could

get my film

processed each day, when we returned in June. Since I would transmit

my photos back to Newsday, each night, I would need a lab that

I could count on to be open late, when I returned from the battlefields.

I gave up on the first couple of film processing labs that I

tried, mainly because of language problems. My lousy French was

ok if

I was asking for directions to the bathroom, but to try to explain

that I would need them to stay open until I returned from the

field and that I only wanted the film processed without the need

for

prints,

was more than my weak French vocabulary could manage.

Quite frankly, I found that the French were rather standoffish.

I have traveled to enough foreign countries to understand that

being

an American isn’t the key to being liked or understood in other

lands. I’ve always despised being thought of as “The

Ugly American” and I’ve always made an effort to

appreciate the people and the culture of other countries. Whenever

possible,

I try to learn at least some basic words of the language wherever

I am. And, in most cases I am rewarded by the locals making an

effort to understand and help me. I have found that if I try

to speak the

native tongue, the locals suddenly speak English. But, with the

French, nothing that I could do would soften their obvious dislike

of Americans.

It was almost as though they resented the fact that their prestige

in the world had diminished and that the US, whom they had once

assisted in our War of Independence from the British, had now

become a world

power and had, in fact, twice come to their rescue in two world

wars.

I continued to try my hardest to be polite and civil, even in

the face of some outright rudeness. I finally found a small Fuji

shop

a few blocks away that was owned and operated by a beautiful,

young French woman with a lovely, lilting name. Marievann. She

spoke

English with a charming French accent and was pleasant enough

to smile at

my brutal attempts to speak her language. I explained who I was

and what I needed from her lab in the way of flexible hours.

I told her

that there would be many nights where I wouldn’t get back

to Caen until late in the evening and I would need to have my

film processed

while I waited. I offered to pay the expenses she would incur

by staying open late and we came to an amicable agreement.

She didn’t understand why I wouldn’t require prints

from my film until I explained that I would have a transmitter

with me

that would accept the color negatives that I would be shooting.

With that problem solved, I then purchased from her, several

lead lined

film bags, with which to bring my current collection of exposed

film safely through the airport X-Ray equipment.

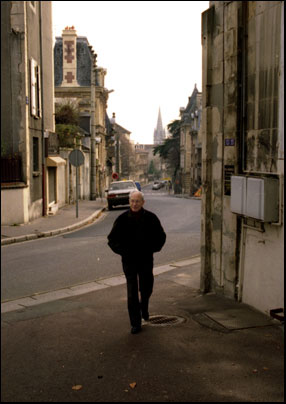

| One day

we were put in touch with a Frenchman who, as a young boy,

had risked his life in the service of the French Resistance

during the German Occupation of France. We met André Heintz,

who was now 73 years old. He had operated as a courier and

took messages through enemy lines to other guerrilla units

operating in Normandy. I photographed him while Jim Kindall

took notes about his story. He described some of the ways he

and other partisans fooled the Germans with counterfeit identification

papers and documents. |

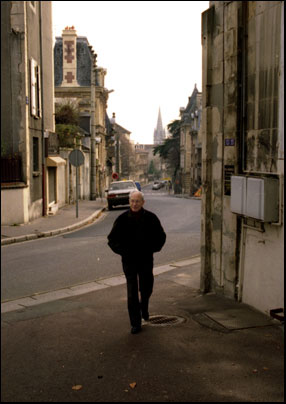

© Newsday Photo by Dick Kraus

André Heintz, a member of the French Resistance, walks

through the streets of Caen.

|

|

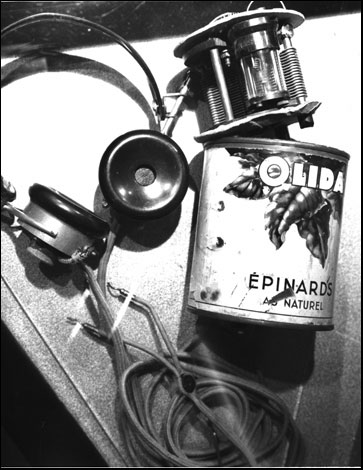

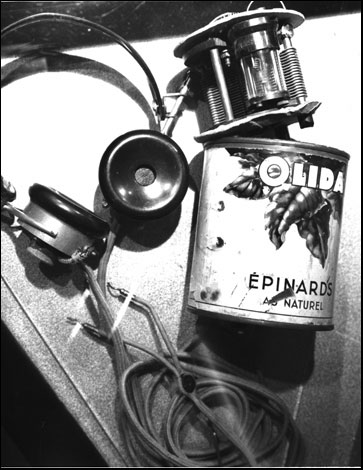

| He described

how they had made a simple short wave radio transmitter and

receiver and managed to conceal it inside of a can of vegetables.

Mind you, this was before the advent of transistors and miniaturized

electronics. I remembered seeing this apparatus on display

at the D-Day Museum in Caen, and I went there and photographed

it. |

© Newsday Photo by Dick Kraus

The spy radio used by the French Resistance, on display

at the D-Day Museum in Caen.

|

|

The proprietor

of our hotel mention to us, one day, that there was another American

currently residing at the hotel. She

was young woman

who was an intern for the Fresno Bee in California. She was

in Caen as part of an intern swap and was now interning for a

local

French

paper. Interesting. Kindall and I looked her up and invited

her to dinner that night. We were dining with the lovely young

American

woman who was one of the administrators of the joint French-American

D-Day Museum.

We had a most enjoyable dinner and it was interesting to hear

how these two American women coped with working in this French

environment.

We also learned about the famed Beaujolais wine of the region.

I am not much of a wine drinker, but I learned that Beaujolais

was

a very seasonal wine and when the first of it appears in the

early winter, it is a much sought after commodity. So, of course,

we

ordered it with our dinner. I found it to be much too tart for

my taste, but

then, as I said, I am not a wine drinker

.

This day happened to be my birthday, and I did wind up drinking

more Beaujolais than I preferred, as my companions toasted my

health and

prosperity more than once. And, as it happened, the next day

was Thanksgiving. The American staff at the Museum was throwing

a Thanksgiving

party for the French staff and the Americans were cooking all

of the traditional holiday cuisine. There would be roast turkey

with

chestnut stuffing, yams, cranberry sauce, pumpkin pie and apple

cider. And, Kindall and I and the young intern were invited.

There was no day off for us, that day, however. Kindall and

I still had work to do. We ranged up and down the coast,

hitting more places that were important to the invasion.

© Newsday Photo by Dick Kraus

The graves of American GI's at the American Cemetery at

Colleville sur Mer. |

|

At Gold Beach,

which was in the British sector, we saw the rusting remains of

the Mulberry Artificial Harbor that had been

erected as a port

facility to unload the hundreds of ships carrying war material

to supply the invasion effort. These were huge, steel caissons

that

were constructed in England and towed across the English

Channel and sunk, one next to another in the shallow waters,

to provide

docks and ramps to allow trucks and tanks to offload from

the ships and

drive ashore.

Fifty years later, there were still several visible across the

hazy expanse of water. You could see whole sections rusted out

of their

sides and they undoubtedly now harbored schools of fish and other

marine life. On this overcast day, there were Frenchmen casting

their baited fishing lines from the shore.

In our travels, we passed through the picturesque village

of Port En Bessin, where at low tide, any boat in the harbor

is left stranded on the harbor bottom as the water ebbs.

OK, this place had no significance to the D-Day story,

but I had to stop and make some photos for myself

© Photo by Dick Kraus

Port En Bessin at low tide.

|

|

When we got

back to our hotel later that evening, we showered and dressed in

our finest and drove to the Museum to

enjoy our Thanksgiving

feast. The food was delicious and Kindall and I were

truly grateful for this opportunity to celebrate what is normally

a family occasion

with this newfound family of Americans and French.

The next morning, there was a package in front of the door to

my hotel room. It was a bottle of Beaujolais from our friend,

the

intern from the Fresno Bee. She had been sent to another part

of the country

and the wine was a birthday gift in appreciation of our friendship

for the past few days. Kindall and I shared it when we returned

to the hotel after a particularly long and grueling day.

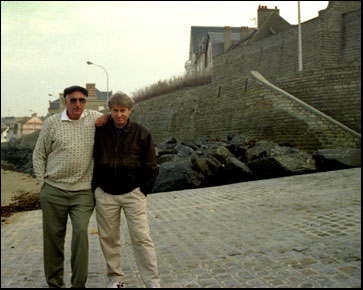

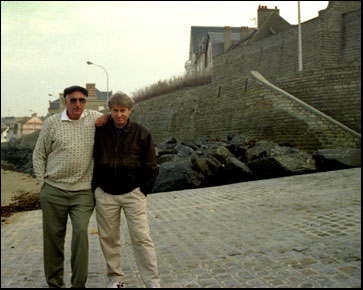

© Photo by Dick Kraus (self

timer)

Newsday writer Jim Kindall (at right) and I take a moment

to snap a souvenir photo in the coastal town of Arromanch.

|

|

After a few

more days, we took a train to Paris and boarded a plane for the

long flight home. The first half of our adventure

was almost

over.

CHAPTER FIVE COMING NEXT MONTH

newspix@optonline.net