This is a tough one to write.

My friend Eddie Adams died last month from ALS, better known as Lou Gehrig's disease, at his home in New York.

When I first heard that he had the disease, which is always terminal, I knew that we had to do a cover feature on his life and work. We started putting it together in August, and hoped that we could get this issue online before he died so he could see it. The big problem with tributes is that generally the people being honored never get to see them. Unfortunately, time ran out.

|

Eddie Adams at his studio Dirck Halstead |

The response to his death has been beyond his wildest dreams. Newspapers all over the world ran lengthy obits. The New York Times devoted the kind of space to his passing that would normally be accorded to heads of state and great artists. As you will see in a special section in this month's Digital Journalist, people who knew Eddie have written about him and their memories of working with him. The tributes range from some of the most famous journalists in the world, right down to young photographers who never met Eddie, but were influenced by him.

The really funny thing is that Eddie Adams was no saint. As one of our editors described him, he was - to put it kindly - irascible. Many of the people who wrote these tributes at one time or another were certainly on his "shit list." These were people who had in some way offended Eddie. The thing was, those who joined the list probably had no idea what they had done. The punishment meted out was exile from his workshop, or worse. People would stay on the list for years, and then as suddenly as they had been consigned to it, they would be removed. Peter Jennings recalls that he found himself on the list after missing a stint on the faculty at the workshop. Several months later, he found himself at Eddie's studio posing for a publicity shot for ABC, along with Barbara Walters and Ted Koppel. During the shoot, Eddie refused to talk to the anchorman, and if he needed to instruct him in the pose, he would turn to ABC News president Roone Arledge, who would have to relay messages between the two.

I have been on the list twice. The first time, when David Hume Kennerly and I had recommended to Time picture editor John Durniak that he cancel an assignment that he had given Eddie, which would have required that he be smuggled into Vietnam through hostile Cambodia in 1976. Kennerly had gotten an assessment of Eddie's chances of surviving the trip from the head of the NSC, who told him flatly that Eddie would be dead within hours of entering the jungles of Cambodia, which was being ruled by the Khmer Rouge. Durniak recalled Eddie, who was already on his way. This resulted in both Kennerly and I being put at the very top of his shit list, and it lasted for the next 10 years. In the early '90s, Eddie rescinded the punishment and for the next two years I was invited to teach at the workshop. Suddenly, though, I was back on the list, and I never had a clue what I had done. It wasn't until the new millennium that the ban was lifted again.

Eddie and I go back a long ways. In 1965, he was working at The Associated Press in New York following stints as a photographer in New Kensington, Pa., and at the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin. I was working as a photographer and running a one-man bureau for UPI in Philadelphia. We both had our eyes on bigger things. One night in February we went to the Gaslight Club in New York for dinner. We were drinking manhattans, and then switched to Stingers. Sometime in the middle of an alcoholic haze, we came up with the idea that we should go to Vietnam. We agreed on a plan. I would go to UPI and tell them that Eddie had told me he was being assigned to the war, and he would do the same at AP, using me as the bait. It worked like a charm. A month later, Eddie and I were both on China Beach watching as the first waves of U.S. Marines came charging ashore.

|

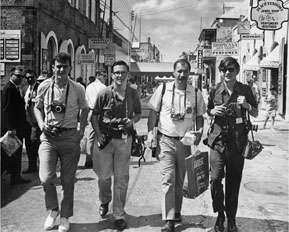

(L to R) Bob Daugherty (AP), Daryl Heikes (UPI), Eddie Adams (AP) and Dirck Halstead (UPI) during the 1970 Governors Conference in Charlotte-Amelie |

For the next 10 years, we would continue this push-pull game. When I took my Time contract in 1972, the first thing I did was to convince Durniak that he needed to hire Adams. Our portfolios were constantly in contention at the Pictures of the Year competitions. By 1976, AP had talked Eddie into returning, where he became the first and only photographer to be awarded the title of special correspondent. In 1980, Adams became a Parade magazine photographer, and went on to photograph over 350 covers, his subjects ranging from presidents and kings to top movie stars.

Oh, yes, I almost forgot! There was that period in the '70s when Eddie tried his hand at soft-core porn. A Time assignment on Penthouse's Bob Guccione led to a friendship, and a series of "Pets" for the magazine.

But in the middle of all this, Eddie gave generously of his talent for nonprofits, including photographing every Jerry Lewis telethon benefiting muscular dystrophy victims and research. In 1995, he created a photo essay for Parade of "the most beautiful children in the world." One photograph of a 3-year-old leukemia victim with her security blanket touched one woman so much that she started an organization, Project Linus, which provides security blankets to children who are seriously ill, traumatized or in need. Today there are more than 300 chapters of the nonprofit throughout the world.

The one photograph that Eddie never wanted to be known for was the one that brought him his fame: the iconic photograph of South Vietnamese Lt. General Loan firing a bullet into the head of a Vietcong who had just killed one of the General's men. Even though the picture is arguably the single photo that did more to change the course of history than any other in the '60s, as it swung American sentiment against the war, Eddie hated it.

Eddie was brave. He was a Marine. Like David Douglas Duncan, that formative experience stayed with him all his life. Early in his coverage of the Vietnam War, he found himself in a rice paddy, under heavy fire. One of the Marines on point had been hit. Eddie ran across a dike ridge as bullets tore through the air around him. He plopped down beside the wounded Marine and yelled for a corpsman, then went back to taking pictures. A few moments later, a terrified young corpsman joined Eddie and the wounded man, and managed to stop the bleeding. For his action under fire, the corpsman was awarded the Bronze Cross. Some months later, Eddie ran into the Marine on a patrol. The Marine told him, "I was so afraid. I knew I was needed, but I couldn't get my legs to work … then I saw you making that run, and I thought if a photographer could do that, then I could too."

For years, Eddie stayed in touch with the Marines that he had covered in I Corps.

Looking at his photographs from his years at Parade, his cover portraits were always done his way. The people he photographed were looking at him. Some were angry, and that tension lives in the work. But always, you feel that these people respected Eddie, and in many cases were even intimidated by him.

His legacy in his work, and the thousands of young photographers who attended his workshop and have gone on to do important photography themselves, will live on for generations to come.

Eddie was a great artist. He created himself, then cast himself for a life role, which in the past two decades assumed its own persona. Always dressed in black, with his fedora and ponytail, he became mythic.

Eddie Adams was brilliant, irritating, funny, angry and complex.

In the last month of his life, he wrote me an e-mail answering one I had sent him, kidding him about always having followed me around. He said, "You don't want to follow me where I am going next. There is a guy in a red suit and horns waiting there."

I have a hunch he went to a much better place, delivered on the love of so many he had touched. In any case, they better be ready on the other end.