|

→ October 2004 Contents → Column

|

An American Legend

October 2004

|

|

|||||||||

|

When I was a photographer's assistant in London in the late 1960s, we used to rent a studio in the King's Road for shoots that required more space than my boss's modest studio allowed. One day we were there, and there was a buzz going around the whole building. Richard Avedon was shooting in one of the other studios. The effect was similar to what I imagine a visit by the Pope to a small country church would be like. For that day we felt aggrandized by his mere presence.

I remember excitedly telling David Montgomery, the photographer who supplied my weekly paycheck, about the great one's presence, to which he replied, "Be glad you're working for me, and not for him."

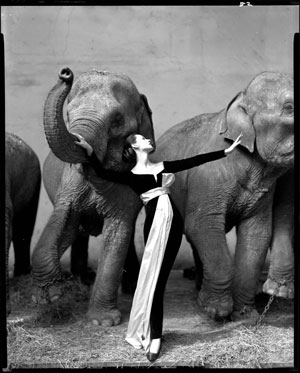

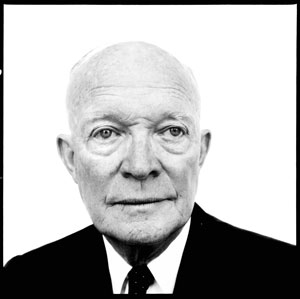

By the time our paths crossed he was already 20 years into one of the most successful and significant careers there has ever been in photography. A New Yorker all his life, he died working for the magazine of the same name, but his initial fame came as a fashion photographer, first photographing the French collections in Paris for Harper's and Vogue in 1947 at the age of 24. Although it is in this genre that many people still think of him, most of his career was spent becoming one of the greatest portraitists of all time, and in any medium.

The link between the two sides of his life's work is that he revolutionized both. He took the sweetness out of fashion spreads and replaced it with an icy, crystalline clarity, often enhanced with a cynical whimsy and wit. His probing portraits shattered the convention of a sympathetic representation; he was the very antithesis of a sentimental observer.

Laura Wilson says of him that there was no one in her experience who had a better comprehension of human nature and its contradictions and complexities. He himself talked about the place that kindness plays in portraiture in a conversation about when he went to take Henry Kissinger's photograph:

"As I led him to the camera, he said a puzzling thing. He said, 'Be kind to me.' I wish there had been time to ask him exactly what he meant, although it's probably clear. Now, Kissinger knows a lot about manipulation, so to hear his concern about being manipulated really made me think. What did he mean? What does it really mean to 'be kind' in a photograph? Did Kissinger want to look wiser, warmer, more sincere than he suspected he was? Do photographic portraits have different responsibilities to the sitter than portraits in paint or prose? Isn't it trivializing and demeaning to make someone look wise, noble (which is easy to do), or even conventionally beautiful when the thing itself is so much more complicated, contradictory, and therefore fascinating?"

Manipulation was a charge that was often leveled against him. There is an often-told story that when he had the Duke and Duchess of Windsor in his studio they started out the session putting on their best royal faces, the public masks that concealed their private despair. If they thought they could get away with this practiced deception, they were up against the wrong photographer. Avedon told them a lie that would shatter their defenses, namely that his dog had just been killed by a taxi. The resulting look of horror and grief destroyed their protective coating, because, as Avedon himself put it, "they loved dogs more than they loved Jews." Is the resulting image an accurate representation of their inner selves? We shall probably never know for sure, but what we do know for sure is that it's closer to whatever the truth was than a lesser photographer who tried to work with what they offered would ever get.

The details of Avedon's remarkable career are well-known and documented: 12 books; over 30 major one-man exhibitions, including such venues as the Metropolitan Museum of Art, MOMA, the Smithsonian, the Amon Carter Museum, the Whitney Museum of American Art; inclusion in the collections of major museums such as the National Portrait Gallery, London, The Kunsthaus, Zurich, and the Musée de l'Elysée, Lausanne. He was an important man, and as such had entrée to other important people. His subjects included presidents and kings; film stars and filmmakers; poets and soldiers.

His last assignment, "Democracy," was a nonpartisan look at the issues affecting the American people in this election year. The New Yorker will publish it in its unfinished state in its November 1st issue.

As she did on many of his lengthier projects, Laura Wilson was helping him set up shoots around the country, and she was with him on the tarmac at Fort Hood, Texas, two days before he died. The temperature was in the high 90s, with heavy humidity compounded by the exhaust fumes of 100 tanks. He used a strange phrase to her, "If I go I'm ready," which she took to mean that he was ready to leave for San Antonio, where he was scheduled to do a portrait. He spent the evening at a lively dinner with her and the assistants, and had a margarita, something that he rarely did. The following day he was supposed to meet her for breakfast, but he begged off, complaining of a headache. Since the session wasn't until the afternoon he decided to sleep until noon, then look at some pictures before leaving for the session. Around the time they should leave, an assistant took him some water and decided to cancel the shoot. Avedon was barely coherent, and couldn't keep his eyes open. An ambulance was called and he was taken to the hospital where he later died as the result of complications from a cerebral hemorrhage. He was 81.

If you go to his Web site, www.richardavedon.com, you will find a passage where he talked about photography in 1970:

"And if a day goes by without my doing something related to photography, it's as though I've neglected something essential to my existence, as though I had forgotten to wake up. I know that the accident of my being a photographer has made my life possible."

For a man such as this, to die in Texas with your boots on was probably not the worst exit.

© Peter Howe

Executive Editor

|

||||||||||

Back to October 2004 Contents

|

|