When John Durniak took over the photo department of Time magazine, the first three photographers he put under contract were Dirck Halstead, Eddie Adams and myself.

Perhaps because both Ed and I had spent our formative years in neighboring Western Pennsylvania mill towns, New Kensington and Tarentum (the two towns had even been big football rivals at one time), two very different people were very comfortable with each other. We used to escape the Time-Life building and drink too much coffee at the AP office a block away. On weekends, I would often end up at his home in New Jersey, where the coffee was even stronger.

At the time, I had hair that reached below my belt. Ed, the ex-Marine, had short hair that was receding. Somewhere in my files there is a picture of me on Ed's shoulders with my hair falling down over his face. It was an attempt on the part of another photographer to get a shot of Ed with a full head of hair. It wasn't that successful, but the "how to" shot was certainly strange.

It was at Ed's home that my hair finally got cut back to a normal length. For a while there were some very macho news photographers, including Ed, carrying a lock of hair in their wallets that would have been viewed with a certain suspicion had others known it was a lock of a man's hair.

|

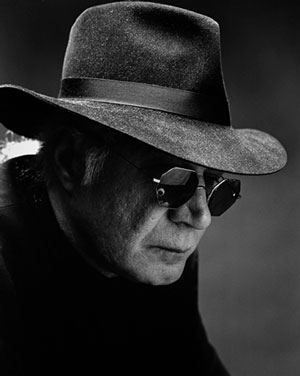

Eddie Adams © Eugene Pierce |

When Ed purchased the farm that eventually became the home of "Barnstorm," the yearly event in which old photojournalists passed on their bad habits to young photojournalists, we would go up on the weekends to fix up the house and barn. Ed said I did less work than anyone. That is not totally true. I think Ed actually did less physical labor. But, of course, he was management, not labor.

We talked about a lot of things, but we didn't talk that much about photography. When Ed was first getting used to using big studio lights, I acted as his assistant on the first job. It wasn't long after that Ed purchased the largest soft light I have ever seen. Ed learned quickly, and the only thing he really needed an assistant for from then on was to carry the world's largest softbox and whatever else he was using.

I taught and spoke at Ed's workshops at the farm in Jeffersonville, N.Y., and attended the annual loft parties. But mostly the time Ed and I spent together was with just a few other people. Our relationship really didn't have much to do with photography. And that wasn't what we talked about. In a way, I thought that would protect me from Ed's somewhat well-known ability to take umbrage at his friends and dismiss them. I was wrong.

We had our inevitable argument over whether I would get his luggage back to his studio after we both came back from a trip on the same plane. I was not asked to speak at the workshop, attend a party, etc., etc. After two years, Ed asked me to teach again at the workshop, but I declined.

Oddly enough, my son became a regular at Ed's workshops and someone who saw him outside those workshops. Ed was exceptionally helpful and kind to him. And, consequently, I always knew what was happening with Ed. Ed and I would occasionally run across each other at some photo function. We were always warm towards each other and enjoyed a long conversation. But there was a line we never crossed.

Earlier this year, Eric Meola said he was going to visit Ed and asked, why didn't I join him? "Why not?" I thought. And then, it turned out, my son was also going to visit Ed. I hadn't seen the Bath House, the East Village building that Ed had bought and converted into his home and a full photographic facility, including rental spaces. This was a project that was hugely important to him. I knew the building from its old, falling down and deserted days. Boy, did he do a job. Perhaps even more than the farm, he had created a home.

We talked. And with immense pride and happiness he showed us his home. This fixture, this workspace, this garage door, this porch. It was the tour. I have never seen him happier. I promised I would see him soon. We hugged. I left.

I'm told that Ed already knew he was sick. He didn't show it. But he never was much for self-pity.

It was a busy summer, and I had loaned my New York apartment to old friends from the Middle East who had come to America to see their son.

As I was thinking of coming to New York, with seeing Ed high on the list of things to be done, I was told that Ed was already weak and having trouble speaking. I had another friend who had died of Lou Gehrig's Disease. Ed was going more quickly than I thought he would. I e-mailed him that I was getting a plane ticket and would see him in less than a week.

I got an e-mail back that said, "Big Bill, I'm still here. Big Ed."

The morning after I arrived, I phoned the Bath House. I was told Ed wasn't going to be able to see anyone that week. I checked a few days later; there was only an answering machine. On Sept. 19th, I sent a brief e-mail saying how stupid I had been and ended by repeating his message, "I'm still here."

At 2 a.m., the early hours of Sept. 20th, Ed died.