PROLOGUE

I was 12 years old when the radio announced that the Allies had

launched the long-awaited invasion of Europe that would ultimately

lead to victory and the end of World War II. That day was June 6, 1944

and would come to be known as D-Day.

Last June was the 60th anniversary of that historic event.

I beg your indulgence as I begin the story, about one of the greatest

assignments of my long career as a newspaper photographer.

D-DAY REVISITED

By Dick Kraus

Newsday

Staff Photographer (retired)

CHAPTER

SIX

Once again, I twisted and turned in the cramped airline seat as

Jim Kindall and I returned to Normandy. This time, instead

of starting our story in Germany, we flew right to France.

We landed at Charles DeGaulle Airport in the early morning and

grabbed a cab to take us into Paris. Our first stop was the

Associated Press office there. I was to have my Leaf Transmitter

upgraded to enable it to interface with the French telephone

system so that I could transmit my photos directly back to

Newsday on Long Island. Even though there were still two weeks

to go before the big June 6th D-Day Anniversary celebration,

there was a tremendous amount of energy in that AP office as

everyone geared up for the event. I was just one of many photographers

who were trying to get AP’s help.

When the conversion was accomplished, Kindall and I took a cab

to the railroad station where we boarded a high-speed train to

Caen, Normandy. It was another beautiful trip through the French

countryside. Now it was early summer and everything was green,

unlike the bleak winter landscape we had experienced on our first

trip here the previous November.

We arrived in Caen in the early evening. This time we had made

reservations for a rented car. By now we knew our way around the

city and had no trouble getting to the Hotel Courtonne. And, they

did have a couple of rooms reserved for us.

The next morning we drove to the headquarters at the American Cemetery

overlooking Omaha Beach. That is where the White House Press Office

would be setting up and where we would get our ever so vital press

credentials. A large press tent had been erected and there were

U.S. Army liaison officers in residence. We checked in with them,

and inquired as to the status of our credentials. A major made

a phone call and informed us that the good news was that there

were White House Press credentials for us. The bad news was that

they were in the hands of the White House Press Officer who was

traveling through Italy and England with the President and wouldn’t

be available to us until they arrived in Normandy. And that wouldn’t

happen until June 5th, the day before the big event. So, for the

next two weeks we would have to depend upon our New York City Police-

issued press cards and hope that they would suffice.

We were expected to come up with daily stories for the paper for

the next couple of weeks. We were to report on preparations for

the anniversary and do stories about the WW II veterans that were

pouring in to Normandy for the occasion.

French school children hold

up souvenir noisemakers called "crickets" for the sound

they make. These were used by U.S. Paratroopers to identify

one another as they assembled in the dark after landing

on the morning of D-Day.

©Newsday Photo by Dick Kraus |

|

The days flew by in a blur as we ranged up and down Normandy looking for our

stories. One of the things that Kindall and I both wanted desperately to

report on was how these old veterans of D-Day would react to being back

where they fought and where they saw their buddies die. Each day there

were more and more of these old soldiers arriving. Kindall wrote and I

photographed but the emotion that we were looking for just didn’t

seem to be present. Probably because many of these earlier arriving veterans

hadn’t landed on the beaches on the first day. They had come ashore

days or weeks after D-Day and weren’t involved in the initial carnage.

|

| We did the best

that we could, but Kindall didn’t want to submit any

of these early attempts. He and I both felt that we stood

a better chance of getting a good story as more old timers

started arriving. In the meantime, we shot the arrangements

being made by the French. Signs and posters were appearing

all over Normandy, welcoming the Allied soldiers and the

other attendees. There were shops and stores springing up

all over the Normandy beaches that were dedicated to selling

memorabilia of D-Day. Maps, books, photo albums, scarves

and tee shirts, model planes, tanks and ships, commemorative

plates and glasses were offered up as remembrances. |

D-Day souvenirs for sale

on the invasion beaches in Normandy.

©Newsday Photo by Dick Kraus

|

|

A souvenir stand at Omaha

Beach.

©Newsday Photo by Dick

Kraus

|

|

A souvenir stand at Utah

Beach.

©Newsday Photo by Dick Kraus

|

|

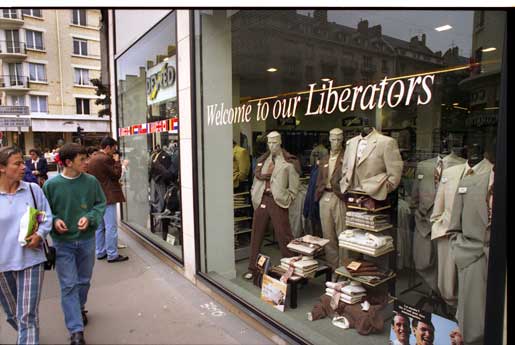

The

French are a strange people. Several months ago, on our first

trip here, Kindall and I had a difficult time getting cooperation

from them. There was a very distinct animosity towards Americans

in evidence. They showed little inclination toward trying to

speak English. Nor did they try to understand my attempts in French.

Granted, my command of the French language is pretty bad. But,

at least I tried to use their language. No one seemed willing

to

make any effort to meet me halfway.

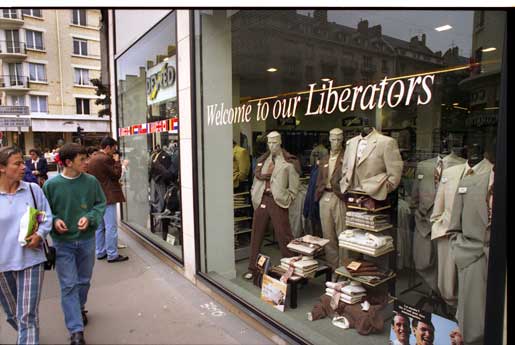

Signs in English

adorn shop windows welcoming "our Liberators."

©Newsday Photo by Dick Kraus |

|

Now,

suddenly, my lousy French was getting me responses. And,

many times the response was in English. What happened in

the intervening months? Did my French suddenly improve? Did

the locals suddenly learn to speak English?

I believe the answer was that the French government reminded its citizens that

there would be a mob of Americans coming to France with a lot of money to spend.

It kind of behooved the populous to extend some basic courtesies to us foreigners.

I don’t mean to sound jingoistic but it seemed to me that the French never

forgave the U.S. for becoming a major power in the world, while their own prestige

kept sinking lower and lower.

|

Late one

night; or I should say, early one morning, Jim Kindall and I

had completed an extremely long day. By the time we

returned to Caen and our hotel and finished filing copy

and transmitting

photos, it was around 2 a.m.. Neither of us had eaten any food

since breakfast and we were famished. There would have

been no trouble

finding a place to eat since most European restaurants open

late and stay open much later than our American eateries.

But, the two

of us were really dragging ass and had a full schedule ahead

of us that day. So, we opted to grab something simple right

near the

hotel. Across the street was a creperie. Here, they served

crepes, which are very thin pancakes that can be filled

with cheese or

fruit. The weather was very mild so we took an outdoor table

in a section that was separated from the rest of the sidewalk

by a

row of potted hedges.

Jim and I chatted about our stories while we waited for our crepes

to arrive. I saw the battered and bloody drunk approach us

from the street. He wore torn clothes and had dried blood crusted

across

one side of his face that had come from a gash over his left

eyebrow. He staggered over to us, separated by the hedge.

“

Allez! Allez!” I told him. “Go away! Go away!” France

was suffering from tremendous unemployment and we were constantly

besieged by panhandlers with their hands out. I was tired,

hungry and cranky and in no mood for this. The man stood there,

swaying

on unsteady legs. He was saying something and I tried not

to pay any attention to him. But, then I realized that he was

speaking in heavily accented English.

“

Sirs,” he was saying, “Forgive my intrusion and my

appearance. I am a French merchant marine sailor and I am very

drunk

and I have just been in a fight. But, I wanted to thank you Americans

for rescuing my country from the Nazis. If it weren’t

for you, I wouldn’t be here today.” And then

he staggered off into the night before either of us could

say anything.

We sat there for several minutes, allowing what this Frenchman

had just said to sink in. I sat with my jaw agape, mortified

about my attitude of a few moments ago. My God. This Frenchman

had just

thanked us for rescuing his country and I had told him to

beat it. In spite of my efforts not to, I had become The Ugly

American.

I was chagrined.

"He was wrong about him not being here if not for America’s

intervention,” I told Jim. “He would be here, but he

would have been speaking German.” I needed to break the

mood, I guess.

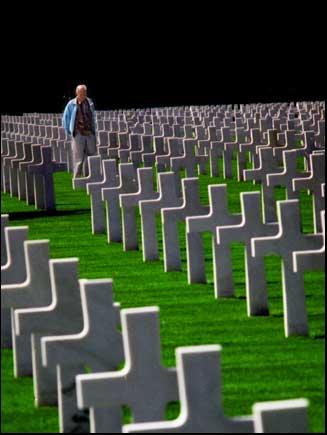

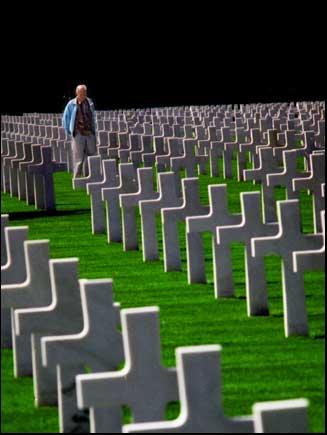

| Every

morning, we would stop at the press tent at the cemetery

to check

on our credentials. Then we would scour the grounds, looking

for a veteran kneeling at the grave of a fallen buddy. Finding

nothing that was any better than what we already had, we

would then travel up and down the coast, checking other battle

sites. |

Days later I was able to

get this shot. I still felt that I should have done

better.

©Newsday Photo by Dick Kraus

|

|

A solitary American

Veteran wanders through the American Cemetery in

Normandy, looking for names.

©Newsday Photo by Dick Kraus |

|

|

We would return to the

Hotel Courtonne late each night and I would rush my film over to

the Fuji shop where I had made arrangements with the lovely Marievann,

the owner. I would leave my color negative film to be developed,

without prints. Then Jim and I would find a restaurant where we would

enjoy dinner. I would stop at the Fuji shop to pick up my film and

then return to our rooms where Jim would type up his story on his

laptop computer to be e-mailed back to his desk. I would go over

my negatives with a loupe and would select several frames that I

felt would be relevant to Jim’s story.

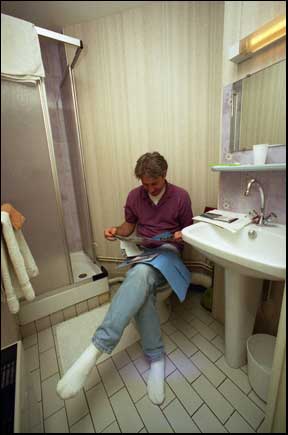

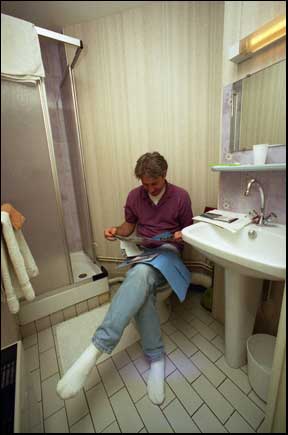

Jim Kindall finds a quiet

spot in his hotel bathroom to go over his notes before

writing his daily story.

©Photo by Dick Kraus

|

|

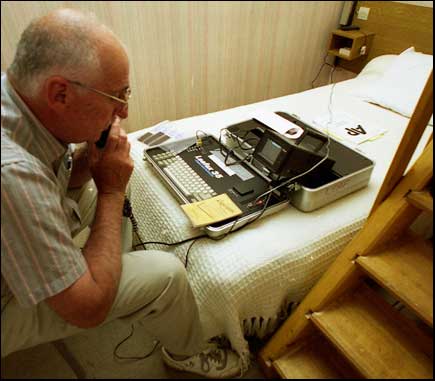

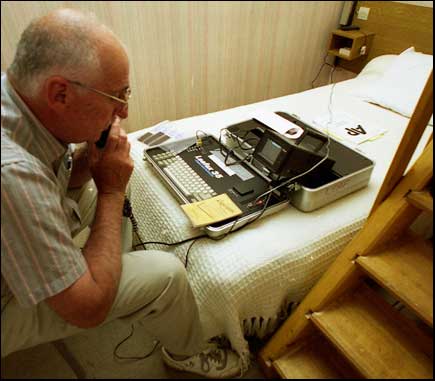

My nightly routine; hunched

over the Leaf Scanner on my hotel bed, transmitting

daily pictures back to Newsday.

©Photo by Jim Kindall

|

|

Hunched

over the Leaf Scanner, I would crop and make adjustments to my

shots and then add captions. I would then

call the special

number back at Newsday and speak to a technician who would

plug me in to the computer there. I was using an old model

Leaf and

had to transmit each photo separately. But, since it was

such

a convoluted system just phoning back to the office, I

would tell

the technician that I had four or five shots to transmit.

Rather than break the connection each time, we would hook up

the computer

and Leaf scanner and I would transmit the first shot. It

took almost a half hour for each picture so the tekkie would

leave

the connection

open and would proceed to go about his other duties, returning

only when the allotted time was up. If he heard silence

when he picked up the phone, he knew that the transmissions were

over and

he would throw the switch enabling him to talk with me.

If

all went well, he would check each transmitted photo and

inform me

if they looked good. Sometimes there might have been a

line break causing a missing section of the photo and I would

have

to resend

it. More often than not, the signal would be broken during

the first transmission and nothing at all would be received

at the

other end. There was nothing I could do but wait until

the tekkie returned to check the system. Which meant that several

hours

were wasted and I had to start all over again. Often I

would

crawl into

bed after one of these long and infuriating sessions, only

to be jangled awake by the alarm after an hour of sleep.

And, we

would

be off to start another quest.

As the D-Day anniversary approached, more and more veterans were

arriving and Jim and I knew that we would find the story

and the photo that we knew would sum up this whole experience.

On this

particular day, the sun was bright and the green grass

covering the American graves seemed even more vibrant than ever.

Still,

the morning passed without anything of substance. There

was something going on up the coast that we wanted to check out,

so

we left

and drove the 40 miles to do that story. But, we felt that

today was

the day we would get what we had been searching for. Jim

made a phone call back to his editor to let him know what we

were

doing.

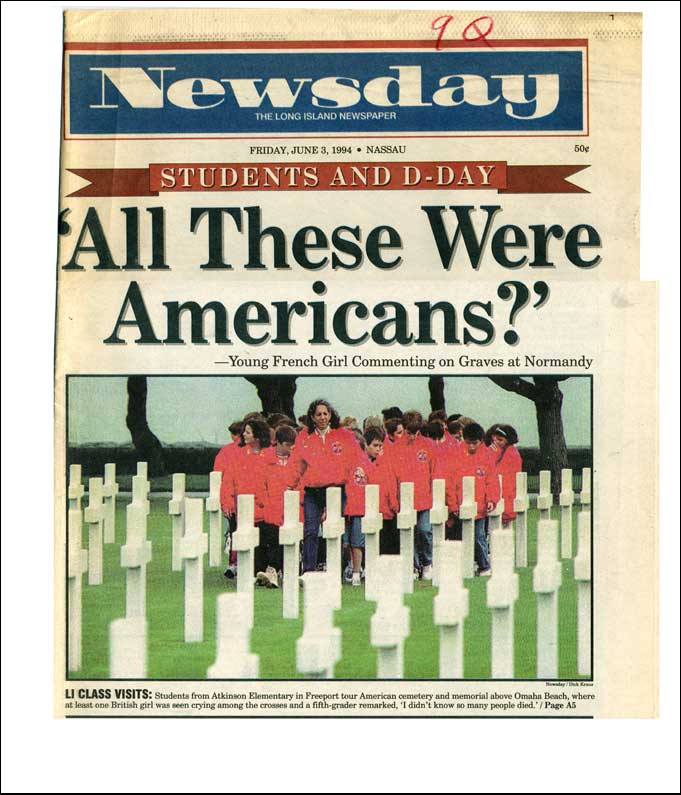

He was told that the managing editor had been looking for

him and he was switched to the ME’s line. Howie Schneider

told Kindall that a group of American schoolgirls from a Long

Island academy

were touring the Normandy battlefields and Newsday wanted

a front page story using that local hook. Of course, neither

he nor anyone

else had a clue as to the whereabouts of the girls. Nor

was he at all interested when Jim told him of our quest for

the elusive

emotional veteran. “Go find those Long Island kids

before today’s deadline!” were our orders.

Jim Kindall was an exceptional reporter and he pulled out every

trick of the trade. He made call after call. We had no cell

phones in those days, so he had to use French pay phones. He

called the

American Embassy. He called any number of French charter

bus companies. He finally got through to the school on Long Island

and was told

that sometime that afternoon the students would be visiting

the American Cemetery from whence we had just come.

We jumped into our rented car and sped through the narrow winding

Norman roads, back to the cemetery. It was late in the afternoon

when we got there and many of the tour busses had already

left the parking lot. We ran through the remaining ones, asking

if any

were there for these American schoolgirls. A woman stepped

forward, telling us that she was one of the chaperones for the

group. Thank

God. If we had missed them there, who knows how or if we

would have ever caught up with them. We were told that the girls

were

being rounded up, as we spoke, to head to another of the

D-Day landing sites.

“

No, no!!” I shouted. The ME had specifically said that

he wanted a shot of the girls in the cemetery. I ran through

the gates

and spotted a large group of young women in the uniform

of their academy, heading for the gate. I quickly identified

myself

and

asked them to wander through a section of nearby graves.

I was able to bang off several quick frames before the girls

were

shepherded

onto the bus.

Whew. Now I wanted to continue our search for the elusive old

soldier, but Kindall said that he didn’t have enough material for

his story about the girls. He wanted to ride in the bus so that

he could interview some of them. I had to drive the rental car

and follow them to their next stop. I never did get a chance to

photograph that emotional vet. But, I did make page one of the

next day’s Newsday with the girls in the American

Cemetery.

The Airborne

GI’s had played a major role in the D-Day

invasion. They had parachuted into enemy held Normandy

in the early morning

dark. They had also landed behind enemy lines in flimsy

gliders and had suffered tremendous casualties. Many books

and films

recounted the valor of those brave men.

To commemorate these events, a huge multi-national parachute exercise

was scheduled to take place in a large meadow outside

of the village of St. Mère Eglise. The Army Press Liaison officers

in the press

tent kept everyone informed of all the happenings regarding

the D-Day anniversary. One of these officers was particularly

helpful

to Kindall and me. He was the one we kept bugging about

our press credentials. He warned us that the drop zone was

expected

to

be particularly muddy. Not just, “Oh my gosh.

My shoes are getting dirty,” muddy. It would,

deep, sucking, thick sloppy like you couldn’t

believe muddy. “People would be losing

their shoes in this muck,” he told us. “Get

boots,” we

were warned. I bought a pair of boots during one of

our excursions through the countryside.

The morning of the big drop, Jim and I left before dawn to avoid

the crowds that would be drawn to this spectacle. We

had been directed to park in the village where there would

be busses

to take the

press to the drop zone. We filed off the bus into the

mud. It was exactly as we had been told; deep, sucking, thick,

sloppy mud. Some

of the glamorous TV standup reporters who had distained any suggestion

of wearing ugly boots over their Gucci pumps were reluctant to

get out of the busses. As we walked along the edges of the field,

many newsmen and women did, indeed, lose their shoes to the sucking

muck. Some clever souls had brought large sheets of cardboard cut

from cartons and they stood on those. Unfortunately, they couldn’t

claim those havens from the slime for themselves alone

and soon there was a crowd of humanity seeking relief

on each of

them.

I, on the other hand, strode bravely through the ankle deep mud, shod in my newly

acquired French rubber boots. This enabled me to take positions otherwise

denied most of the rest of the newspukes who weren’t as well advised

as I. However, to the credit of some, the more dedicated removed their shoes

and socks, rolled up their pants and waded into the goop. Bravo! |

| While a TV reporter next

to me tries to keep his sneakers dry by standing on

a folded step-stool, I am standing in the wet and muddy

field in my boucage boots. (Boucage is French

for meadow, I believe.) |

|

Heralded by the

thunder of many large planes overhead, paratroopers

fill the sky.

© Newsday Photo by Dick Kraus

|

|

Soon the sound of many planes reached us and we looked up to see hundreds of

troop carrying transports flying low across the meadow. Little black dots

tumbled from them and fell through the air. Suddenly, white blossoms billowed

out behind each dot as hundreds of parachutes deployed. The figures grew

larger as they descended and we had a clear view of the paratroopers landing.

|

|

Paratroopers from several

nations fill the skies and then come to earth in the

muddy fields of Normandy, just as those soldiers did

on D-Day, 50 years ago. Only then, they landed in the

early morning dark.

©Newsday Photo by Dick Kraus

|

|

| They gathered up

their chutes, formed up and marched off the field. No sooner

was the meadow empty than another formation of planes flew

over and more dots tumbled out. In addition to American troopers,

there were airborne units from all the Allied Forces. My

two Nikons joined the clatter of hundreds of other shutters

around me, as photographers from newspapers around the world

captured this monumental display. There were pictures everywhere

that you pointed your lens. Behind us, crowds of French spectators

cheered as each wave of planes disgorged their human cargo. |

Parachutes descend over

Normandy.

Newsday Photo by Dick Kraus

|

|

We had been told that there would be a special flight of WW II

airborne veterans who had made this drop 50 years

earlier on D-Day. Now mind you, these were men who were now

in their 70’s.

They had to undergo special testing to ensure that

they were physically capable of enduring this jump.

A flight

of vintage World War II C-47’s

came into view. They were the same aircraft

that had carried these old soldiers into battle 50 years earlier.

That grew

a lump in

my throat. I watched the black dots emerge and

I thought

of how these same men had risked their lives jumping

into a strange and hostile environment so many years ago.

The vets had wanted to use the combat parachutes that were still

used by today’s airborne soldiers. But the French government

was concerned about their safety and required them to use the safer

and more reliable sport chutes that sky divers use today. So, it

was a different shape that bloomed behind each jumper. That didn’t

diminish the feeling of pride that I felt as

these old timers floated to the ground.

A WW II Vet jettisons his

tangled main chute (seen at upper left) and floats

to safety with his reserve cute.

©Newsday Photo by Dick Kraus

|

|

Suddenly,

from the crowd of spectators behind me, I heard a gasp. I

whirled around and saw them looking up and pointing skyward.

I followed their pointed fingers and saw one of the old timers

plummeting to earth with his useless parachute tangled into

a knot. It looked like certain death for this brave soldier.

But, he pulled the cord on his reserve chute. It deployed

moments before he crashed to his doom and he floated into

the crowd of cheering French men and women.

I must have been hitting my motor drive button without realizing it, because

I ended up with a decent sequence of photos. Sometimes, Argus, the many-eyed

god of Greek Mythology, looks after us poor, bewildered human photographers.

Thanks, Argus. |

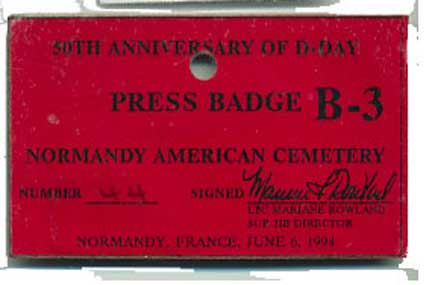

And then it was June 5th, the day before the big anniversary dog

and pony show. Today, Jim and I were supposed

to go to the press tent at the American Cemetery to get our coveted White House

Press

credentials with which we could gain access to

President Clinton as he visited the various invasion beaches and memorial sites.

The trick would be getting to the cemetery to

get the cards. The

French had announced that there would be a day-long

lock down of all roads in the area on June 5th to allow them to test their security

procedures. There would be many heads of state

at the next day’s

events and the French wanted to ensure that there

would be no incidents to mar the festivities. So, we were

told that

at 5

a.m., all roads

leading to D-Day sites would be sealed unless

you had the required credentials. Unfortunately, our required

credentials

would

be at the press center, 40 miles from our hotel.

At 4 a.m., Kindall and I were on the road, heading north. The roads

were jammed with traffic trying to beat the curfew.

Jim drove and I sat next to him with road maps of the area,

trying to work our

way around traffic jams. By 5 a.m., it was growing

light and it was obvious that we would fall far short of our

destination

before the roads were sealed. Shit!! We would really

be

screwed

if we

didn’t get those all important press credentials.

And then, there it was. The first roadblock. Traffic came to

a standstill as French gendarmes and military

police turned traffic off the main road. We inched forward, hoping

to be

able to convince

the authorities ahead that we were really American

journalists trying to get our press cards. When we finally

got to

the barricaded intersection, the police didn’t even give

us the opportunity to explain our situation. With whistles

screeching from their

mouths and their hands on their guns, we were bruskly

directed off of

our intended route and onto a side road heading in

the wrong direction.

As Jim drove us down this secondary route, I checked the map

and saw that it went nowhere near the press center.

I told Jim to hang

a left at the next side street. This would take

us through the town we were in and would bring us onto a road

that

followed

the

coastline north, towards the American Cemetery.

I knew that there would be another roadblock somewhere ahead,

but

I

saw that

there

were many little farm roads indicated on the

map, that might take us around the roadblocks. Worst case scenario,

if

we got

close

enough, we could dump the car and walk up the

beach

to the cemetery to get our credentials.

Several hours passed as we wove around towns and villages and

roadblocks, getting closer and closer to our

goal. There was just one more

stretch of road left to navigate before…OH, SHIT!! Here was

another blockade. I saw traffic stalled for almost a mile and up

ahead were the gendarmes and military waving drivers away. I checked

the map and damned if we weren’t in an area where

there were no small secondary roads. There was no place

else to go,

and we

were so goddam close.

| My mind was in

turmoil and I was really frustrated. I turned to Jim and

told him to drive the car up on the shoulder of the road,

turn on his headlights, lean on the horn and gun the engine.

I leaned out of my window and waving my New York City Police

Press Card in my hand, I screamed, “JOURNALISTE! JOURNALISTE!” at

the top of my lungs. The startled gendarmes waved us through

the blockade and within minutes Kindall and I, laughing our

asses off, were picking up those magic press credentials

at the press center. |

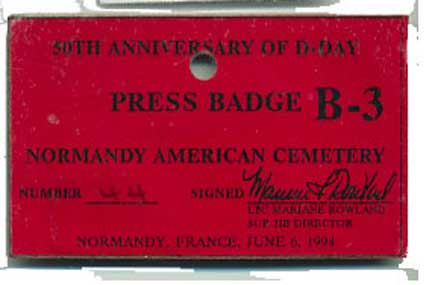

| The New York City Police

Press Card that got us past the road block. |

|

| Finally, the long awaited

D-Day Anniversary Press Card. |

|

For the

rest of the afternoon, we attended briefings detailing the timetable

for the D-Day ceremonies the

next day. The president would be attending several events, culminating

in speeches

and

the laying of wreaths at the American Cemetery

in

the afternoon. All of these would be covered by pool assignments

so I had

to sit in on several of these briefings to put

my

name in

for pool slots.

I was lucky and drew two good ones. The first

was an early morning ceremony at Pte. Du Hoc, where the American

Rangers

had

scaled

the cliffs to silence German shore batteries.

The

second was the big one at the cemetery.

Quite frankly, I didn’t need to be at any of these things.

To be blunt, my job was over. Jim and I had supplied

stories and photos for the daily paper for the past two weeks

leading

up to

this time. Our White House correspondent, who had been

traveling with Clinton, was now responsible for coverage

of the D-Day

anniversary events. She would be in the front rows with

the rest of the White

House press corp, and wire service photographers would

be in the prime positions to make photos to go with the stories.

Kindall and I were only supposed to supply sidebar accounts

of the veterans

who were in attendance.

But, like most veteran newspukes, who are like firehouse Dalmatians,

we couldn’t resist the call to action when the alarm sounded.

And so, bright and early on the morning of June 6th, 1994, I was

getting off the press bus at Pte. Du Hoc. There was a thick fog

hanging over the area and you could barely see the end of your

long lens right in front of your face. Too bad. There were great

photos to be made. There was an armada of warships standing off

shore in the English Channel, much like the morning of June 6th,

1944. In fact, Clinton had spent the night aboard the American

command ship before being airlifted by helicopter to the memorial

site. Even though I had a pool spot, it was a low-priority position.

The better spots went to the White House pool and the wire services

and big name publications. It didn’t bother me, because I

wasn’t really expected to be able to get anything

for Newsday. The low-priority media were led to a grassy

field

near the memorial

where the prez would disembark from his chopper. From

there, he would walk to the memorial to lay a wreath

and greet

the American vets who were assembled there.

President Bill Clinton reaches

out to greet American D-Day Veterans at the Pte. du

Hoc war memorial.

©Newsday Photo by Dick Kraus

|

|

When

the chopper landed, I was in a good position to get Clinton

walking from the bird and shaking hands with the old soldiers

along his route. It made a good shot. It would have been

a great shot had we been able to see the naval ships off

shore. Too bad. Before the speeches began, a member of the

press liaison came over to us and brought us over to a position

from where we could photograph the speeches. It turned out

to be just about as good as the one being occupied by the

White House Pool. How about that? After the speeches and

wreath laying at the memorial, I got even better shots of

Clinton pressing the flesh with the vets as he headed back

to his helicopter. This time I was even closer. |

The chopper took the president to his next stop and the bus returned

the rest of us to the press center at the

cemetery. I had several hours to kill before my next pool shot

so

I found Kindall.

He had

been interviewing some of the veterans who

were waiting at the cemetery. He pointed out some of them and

I

made some

pictures

of them.

While I had some time, I decided to try to get my early shots

transmitted back to Newsday. There was no

need to go back to Caen to get my

film developed and then to my hotel to transmit.

Associated Press had set up their facilities right at

the base of

the cemetery memorial, complete with color film processors

and transmitters. I walked

over there with a pocket full of color film

and filled out the

necessary paperwork and handed off my film

to one of the

AP

techs. The place was filled with photographers

from all over the world,

doing the same thing. It would probably be

hours before they got to my film. Everyone had to take a number.

I went

outside and sat

down against a tree, waiting to be told that

my film was done so that I could select the few frames to

be transmitted.

I

was talking

with another photographer for just a few

minutes when I

heard

my name called. “Kraus! Is there a Dick Kraus

from Newsday here?”

“

Yeah. Here. What’s up?” I asked as I walked over

to him.

“

Do you have a son named Doug who was a student at the University

of California at Long Beach?” he asked.

“

Yeah,” I answered. “Why?”

“

He was my roommate.” He introduced himself and told me

to make sure I gave my film to him each time

I came in and he would

see that it got right through without waiting.

Jeez! Thanks for being my son, Doug, and for going to college

in California instead of New York.

Later that afternoon, the crowd waiting at the cemetery began

to stir. Clinton had arrived. We saw the helicopters circle

the area and settle to the ground in a field just outside the

cemetery perimeter.

I went to my pool position, which once again was a low-priority spot toward the

rear of the bleachers that had been erected. But, as before, someone came

and gathered up the White House Press pool and escorted them to another position

at ground level, just to the right of the memorial. And we were free to move

forward and occupy their former positions. |

Newsphotographers photograph

the crowd waiting to hear the president speak at the

American Cemetery.

©Newsday Photo by Dick Kraus

|

|

President Clinton and WW

II Veterans salute the fallen D-Day vets at the American

Cemetery,

©Newsday Photo by Dick Kraus

|

|

The morning fog

had long since burned off and the afternoon was bright and

sunny. With my 300mm lens, I was able to get tightly cropped

images as the president spoke and then laid wreaths at the

base of the memorial.

Then it was over. Clinton left to go back to Washington and I headed to the AP

facilities to look up my new friend. My film was processed and picked. AP asked

to use a couple. Since Newsday is an AP member, they had that right and in view

of the exceptional treatment I was given, I could hardly refuse.

The next day, Newsday ran my photo full Page One, of the president and two WW

II

veterans saluting the fallen soldiers of D-Day at the base of the memorial. |

It’s

things like that which makes the job and all of the required

effort and frustration so rewarding.

There was just one thing that I wanted to do before I called

it quits. I wanted to photograph Omaha Beach on June 6th, 1995,

50 years after that bloody D-Day.

Fifty years after D-Day,

the blood and the wreckage have washed away from Omaha

Beach and the locals enjoy a more pristine and bucolic

scene.

©Newsday Photo by Dick Kraus

|

|

The next

day I flew home.

The

End

EPILOGUE.

This

story began for me in 1944 when, as a 12-year-old child,

I listened to the radio reports of the invasion. I grew

up with books and movies depicting the events of that day.

To be chosen

to go to Normandy to document that struggle and to photograph

so many of the brave men and women who participated in that epic

event was indeed a great honor for me.

I consider

this to have been the greatest assignment of my career. Thank

you for taking the time to share the occasion with me.

Dick Kraus

http://www.newsday.com

newspix@optonline.net