|

→ May 2005 Contents → Feature

|

Among the Dreamers

|

|

|||||||||

|

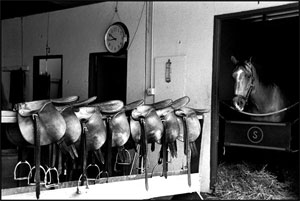

May is the month of the Derby, the time when America renews its annual obsession with the Triple Crown, and once again we yearn to fall in love with an unlikely horse with a silly name like Funny Cide or Smarty Jones. Although the glamour and large purses, the packed grandstands and mint juleps intrigue us briefly through the Derby, Preakness and Belmont, thoroughbred racing is a 365 days per year operation conducted mostly by unknown and unseen workers in a world that few of us will ever enter or experience. It is an almost secret society with strange names and occupations. There are bug boys and clockers, hot walkers and gallop boys with horses that might be mudders or rabbits. Like most closed societies it does not readily allow outsiders access to its inner workings, but Sarah Hoskins is hardly a stranger in their midst. She has been hanging around tracks photographing the daily activities of racing for more than eight of her 20-plus years as a photographer.

To hear her describe the jobs that the workers of the backside perform to earn a living she might be defining her own occupation, or that of any other working photojournalist. The work, she says, is hard, itinerant, poorly paid, sometimes dangerous, and most people do it because they love it. A hot walker, for instance, is someone who walks a horse who has recently galloped until they are cool enough to safely eat and drink without risking colic, a cramping of the intestines that can be fatal. As the photographer says of them, "That's not an easy job. You're walking around a 1,500-pound animal who can be an absolute lunatic." Then there are the Bug Boys, the young apprentice jockeys who can ride fine at 15, but a year later are too tall and too heavy to ever achieve their winning-post dreams. For all their strength thoroughbred horses are remarkably fragile, needing the constant attention of veterinarians who are universally called "Doc," to such an extent that Hoskins still doesn't know the real names of some that she has been around for over eight years. At the upper levels of the hierarchy are the jockeys. When asked what they are like, she answered, "Short." She went on to say, however, that although she has never been allowed into the jocks' room, she has seen them with their shirts off, and says that they are all muscle.

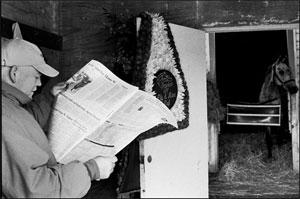

If you ask her where her work on the backstretch has appeared she will tersely tell you "in my filing cabinets." Pretty much all of her racing photographs are unpublished, and although she is frustrated by this, and dreams of a publisher seeing them and offering her a book contract, she is philosophical about it, acknowledging that her subject has limited interest. She also takes her inspiration from the photographer she has been corresponding with for five years and met for the first time this spring, Paul Kwilecki, who has photographed his hometown for 40 years. She says of him, "He's an amazing photographer and when I kind of wonder if I'm doing the right thing with my project he put things in perspective. He's from a town called Bainbridge, Georgia, and he just goes about and does his work. I thought, 'Okay, this is what I should do.' I think you need to do the work because you want to. You need to like what you're making photographs of."

"I do this work at this point because I just love making pictures; I just like being around the backside. It's the place where I like to be more than anything. I remember mornings in early September, when it's cool and breezy, and the leg wraps are blowing, the horses are walking around, and the people are great. I don't think half the people on tracks that I go to regularly know my name. I'm known as the picture lady, and you know, that's just fine. I could be known as a lot worse."

She is seeing changes taking place in thoroughbred racing - fewer people and more slot machines. Today's gambler has so many more outlets for his or her obsession, but Sarah still sees people come out for a good story. During the Smarty Jones frenzy last year 5,000 people gathered in the early morning to watch trainer John Servis put the horse through his paces at Philadelphia Park. She comments, "People are dreamers in the horse racing business; everybody is a dreamer. They're all looking for that big horse. Everyone wants to have a big horse."

To their number add one more dreamer, a photographer named Sarah Hoskins, the picture lady of the backstretch.

© Peter Howe

Executive Editor

|

||||||||||

Back to May 2005 Contents

|

|