Editor's note:

Thirty years ago, on April 17, 1975, the war in Cambodia ended. The Khmer Rouge had occupied Phnom Penh. Four years of terror and Stone Age communism followed.

About two million Cambodians, a quarter of the country's population, perished. This report and the accompanying video show were prepared for a major commemorative exhibition and weekend discussion about the past and future of Cambodia, held recently in Bonn-Koenigswinter, Germany.

For a Vietnam correspondent like me the Kingdom of Cambodia in the 1960s was a neighborhood Shangri-la, a country for an exotic vacation - providing a visa was granted by Prince Sihanouk, who had broken off relations with the United States. The wonders of the Angkor temples, cradle of Cambodia, were still hidden in the jungle awaiting discovery. I watched Larry Burrows photographing them in moonlight.

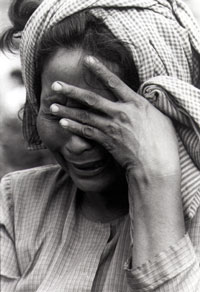

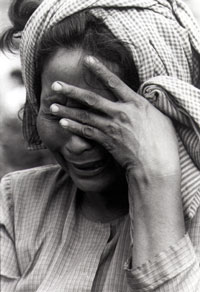

|

Phnom Penh, Cambodia, 01/26/74: Tears of war. Sou Vichith/Gamma |

Everybody covering the Vietnam War knew that the North Vietnamese and the Vietcong were using the Ho Chi Minh Trail, which stretched north-south on Cambodian territory, alongside the border with South Vietnam, and maintained military camps and command centers in Cambodia. However, Prince Sihanouk always denied it. On the surface Phnom Penh was a paradise of peace. No napalm clouds on the horizon, no rockets, no hectic chaos, as in Saigon. Instead there was the endless Mekong, golden palaces and a cool pastis at the swimming pool of the Hotel de Royal. During the early years of the Vietnam War I had visited Cambodia often, although only a few times with a visa and on a peaceful mission. Again and again I accompanied South Vietnamese troops who pursued Vietcong guerrillas across the Cambodian border, bringing napalm, war and horror to Cambodia.

After the CIA-engineered coup d'état in 1970 (which replaced Prince Sihanouk with General Lon Nol), it was as if a sudden flame had set fire to the whole country. From the Hotel de Royal one could see and hear the daily B-52 bombing on the opposite side of the Mekong. Suddenly the Vietcong and the until-then barely known Khmer Rouge seemed to be everywhere. Travelling the roads became dangerous and remote villages were devastated or taken over by the Cambodian guerrillas in black uniforms and balloon caps.

The night soon belonged to the enemy. It became a civil war of shocking brutality on both sides, punctuated by the daily "secret" American carpet bombing, which apparently aimed for the total destruction of rural Cambodia. Soon there were dead and wounded everywhere and the Cambodians had become a nation of refugees. Meanwhile the stranglehold of the Khmer Rouge became tighter.

|

Former King Norodom Sihanouk, rear, looks on as his wife Queen Monineath kisses his son and successor, King Norodom Sihamoni, at the bathing ceremony, one of the coronation ceremonies at the Royal Palace in Phnom Penh, Friday, Oct. 29, 2004. Cambodia prepared to crown a former ballet dancer and political unknown as king, replacing his father, Norodom Sihanouk, who for over 60 years led his country through wars, revolution and moments of triumph. Nathan Dexter/AP Photo |

The press corps set up camp in Phnom Penh, primarily in the comfortable Hotel de Royal. As in Saigon, daily war bulletins were issued. But there was a big difference. There were only a few helicopters in Cambodia and nobody really knew who controlled what territory. The front was everywhere and during the first months of the war, 25 journalists were killed, captured and slaughtered - or they just never returned from a drive down one of the dangerous roads leading out of Phnom Penh. For all journalists, photographers, writers and TV crews the war in Cambodia became more dangerous by the day, with risks that could not be calculated as in Vietnam. South Vietnam had at least a well-organized army and there were half a million American soldiers with thousands of helicopters. The Cambodian soldiers were mostly inexperienced teenagers, just as naïve as the young reporters. During the last year before the fall of Phnom Penh to the Khmer Rouge, the once so pleasant capital became an inferno as we had never experienced in Vietnam. Two million refugees overcrowded the once elegant boulevards and suburbs. Parts of town burned out and were flattened by the rocket and artillery attacks of the Khmer Rouge.

The fact that photographs tell the story of these terrible days today is due mainly to Cambodian photojournalists who worked for the western media. Foreign journalists could not report anymore from the countryside without taking terrible risks. With very few exceptions, these brave Cambodian reporters became victims of the Khmer Rouge, who worked and starved them to death or simply murdered them. Only a few survived, like Dith Pran, the Cambodian colleague of The New York Times' Sydney Schanberg and hero of the book and film "The Killing Fields."

|

A Cambodian man walks past one of the many killing fields sites at a school on the outskirts of Phnom Penh on Sunday, July 27, 1997. The previous day, Pol Pot and his genocidal clique were put on public trial in Anlong Veng by his own comrades and sentenced to life in prison. Richard Vogel/AP Photo |

On April 17, 1975, 30 years ago almost to the day, photoreportage from Cambodia ended abruptly. With the total population, the Cambodian photographers were marched out of the city and the few western reporters still around were interned at the French embassy and later trucked to the Thailand border. All communications were cut off. During the next four years, while the Khmer Rouge killed off a quarter of the country's population, not much was heard of or seen out of Cambodia. The interest of the world turned elsewhere. Even after the overthrow of the Pol Pot regime by the Vietnamese in January 1979 only fragmentary information emerged. With the Vietnamese, the first foreign correspondents returning to Phnom Penh were from communist East Germany. The photographic documentation of the Khmer Rouge's four horror years that exists today originates from primitive propaganda efforts of the Pol Pot government and from the regime's bookkeepers of death, who catalogued tens of thousands of their victims and photographed them before and after they were "smashed."

Nhem Em was among the first Khmer Rouge photographers who took portraits of the doomed prisoners. He worked at the documentation center of Toul Sleng prison, also called S-21, one of the many torture centers and killing fields near Phnom Penh. At this office, taped interrogation reports were typewritten. Handwritten confessions had to be recorded. Each prisoner ended with a voluminous file. The photo section of the documentation center was headed by a man called Suos Thi. His photographers were asked to take frontal portraits of each new arrival at the camp, usually before their first torture session. However, they were also asked to take pictures of prisoners after torture or, in the case of more prominent victims, after they had been killed, usually by having their throats cut. Nhem Em reported that such pictures were often delivered personally to the 'brothers' of the secret Angkor regime. Prisoners who were brought to S-21 during 1978 were usually photographed with a sign around their neck, sometimes with their name and number written on it. In May 1978, for instance, 791 prisoners were photographed.

One of the only seven survivors of Toul Sleng, the painter Vann Nath talked about his detention there in an interview with AP:

"They took my photograph and asked what I did, both then and at the time of the previous government.

I told them that I used to be a painter and now I was a farmer, like everyone else. But they just sent me to Building D, on the second floor, and put me in a cell with other prisoners. There were about 60 prisoners in the room. Our suffering was unbearable. Our only right was just to lie down. If we wanted to speak or to sit up, we had to ask a guard's permission. They gave us two meals a day, one at eight in the morning - two or three spoonfuls of rice soup - then again at eight o'clock at night - two or three spoonfuls of rice soup. In between, we had nothing to eat. The prisoners died, one after another. Some were taken for interrogation and never came back. We could hear the screams of prisoners being tortured. And we knew that one day we too would be screaming like those prisoners. Actually I was tortured. They asked me questions, and if I couldn't answer them they gave me electric shocks until I fell unconscious. Then they splashed water on my face, so I regained consciousness. Then they asked another question. If I couldn't answer, they gave me another electric shock. This they did many times.

"One day, though, they moved me from the crowded cell, because I'd told them I was a painter. They ordered me to paint something, to prove it. When they saw that I could paint, they kept me, to be used. So I think it was because of my skill as a painter that I survived. They asked me to paint a picture of a man that I couldn't identify. They called him 'Brother Number One' or 'The Party Leader.' I only found out it was a picture of Pol Pot later on."

|

Scene with shocked survivors after a February 1974 rocket attack by the Khmer Rouge on an overcrowded refugee slum outside Phnom Penh, Cambodia. The attack's toll: 140 killed, more than 300 seriously wounded, and 1,500 dwellings destroyed. Photo by Carl D. Robinson/AP Photo |

The documentation bureau was a dangerous workplace. Between 1976 and 1978 at least 10 documentation workers were arrested, tortured and killed - maybe only because of a spelling mistake. Toul Sleng photographer Nhem Em was a 10-year-old peasant boy who joined the Khmer Rouge. The organization sent him to China in 1975 to study photography. In 1976 he was assigned to S-21, where he worked with five other photographers. He remembers that one of them was killed. Em himself spent a year in a brutal "reeducation" camp, because he had printed a picture of the then-unknown to him Pol Pot with a spot above one of his eyes. When it was reported that the flaw had already been on the negative when a Chinese photographer had developed the film, Nhem Em was released back to his job at Toul Sleng. Pol Pot had visited China in 1977. Nhem Em only parted from the Khmer Rouge in 1996, when the organization collapsed.

Hundreds of the photographs from S-21 have been exhibited at the Toul Sleng Museum since 1980. The museum was set up by Vietnamese curator Mai Lam and first headed by a S-21 survivor, Cambodian Ung Pech. With the Vietnamese came photographers from East Germany (the DDR), who began printing the thousands of negatives. Fifteen years later two American photojournalists, Doug Niven and Chris Riley, took over. Niven and Riley's Photo Archive Group cleaned, catalogued, enlarged and digitized about 6,000 of the negatives that were in the Toul Sleng files in 1994-1995. They published some of the mugshots in their beautiful, moving book "The Killing Fields."

|

A father holds the body of his child as South Vietnamese Army Rangers look down from their armored vehicle, March 19, 1964. The child was killed as government forces pursued guerrillas into a village near the Cambodian border. Horst Faas/AP Photo |

Most of the photographs that survived can be viewed at a Web site of the Cambodia Genocide Program of Yale University (New Haven, Conn.). A sister organization of Yale's Program, the Documentation Center-Cambodia (DC-Cam) in Phnom Penh, cares today for the thousands of written confessions, the photographs and all other documents that may throw some light on one of the darkest chapters of 20th-century history.

The Khmer Rouge fled in 1979 to the jungles in northern and western Cambodia and reverted to guerrilla life. They left behind thousands of killing fields and a traumatized people that reluctantly welcomed the Vietnamese as their liberators. Still caught in the mentality of the Cold War, the West, and especially the U.S.A., encouraged the Khmer Rouge to continue their fight against the Soviet-supported Vietnamese for another decade. The Khmer Rouge kept their seat at the United Nations and 'brother number five,' Khieu Samphan, remained as nominal head of state, with an office in Paris. Only when the Cold War ended did the Khmer Rouge ran out of steam. They lost the elections which had been organized by the U.N. and thus their international support which had not ceased for 10 years after the killing fields had been discovered. Only in 1995 did the U.S. consider the Khmer Rouge officially a terrorist organization. Units of the Khmer Rouge deserted to the new Cambodian army. Their leaders collaborated with the new government and received pensions. Only a few were arrested; none have been tried so far. The Khmer Rouge was dissolved in 1999.

Many of those responsible for the genocidal mass murder of the Khmer Rouge survive as free citizens in Cambodia. The torturers and guards of Toul Sleng are today gardeners, fishermen and grandfathers. Pol Pot, 'brother number one,' the party secretary and head of the Khmer Rouge, died under odd circumstances in his bed in a jungle camp near the Thai border. Comrade Duch, the commander of S-21 and responsible for the torture and death of more than 14,000, turned to religion. It did not help him that he became a preacher of an American Christian sect; he spends his days in solitary confinement in a Cambodian jail, as does Ta Mok, the 'one-legged butcher.' They are waiting for the beginning of the long -delayed trials of Khmer Rouge war criminals. About 50 of them are marked for an international trial if the expected $56 million costs can be found.

|

Cambodia 11/10/74: Two young Cambodian soldiers, with their rifles in hand, carry ammunition and a mortar plate to reinforce Cambodian government troops near Trapeang Kraloeung on Route 4, 36 miles southwest of Phnom Penh. Highway 4 was formerly Cambodia's lifeline to the sea. The road had been closed since early in the previous year. Heang Sun/AP Photo |

Thirty years later tourists on a stopover in Cambodia go to see the wonders of Angkor again. The streets of Phnom Penh are crowded with young people and motorbikes. The sun sets with dramatic colors over the Mekong and the freshly gilded palaces, now occupied by a new king, Prince Norodom Sihamoni, son of Prince Sihanouk and his wife Monique.

On the surface Cambodia seems alright and at peace.

But photographs from the past decade also show that the trauma of the Khmer Rouge reign of terror lives on in every Cambodian family. Cambodia is one of the poorest countries in the world. Cambodia suffers from the global plagues of AIDS, drugs and unemployment and the land mines and unexploded bombs of the 30-year-old war are still everywhere. Year after year thousands have been injured and killed by mines. Cambodian politics brought coup d'états, open war between political factions and politically-motivated murders. On the other hand, there have been three free elections with about 80 percent voter participation and travel through the country is today (mostly) safe.

Cambodians still have difficulties finding the peace the country needs to recover from its nightmares.