|

→ May 2005 Contents → Feature

|

The Attention Seeker

|

|

|||||||||

|

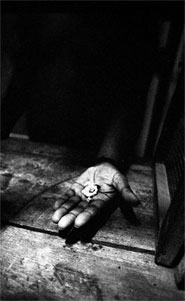

Antonin Kratochvil wants your attention, not for his own sake, but for the sake of the planet on which we live. His latest book, Vanishing, published by de.MO, is his most recent attempt to get you to pay attention to the issues to which he has dedicated much of the last 16 years of his life and career. The items whose rapid disappearance disturbs him include forests, wildlife, indigenous cultures and social structures, and even the civil liberties of the citizens of the United States. As a photographer he believes that it is his job to go and photograph "things people usually don't see, or things I think they should see."

Antonin's attention span is wide, and he attacks the issues of environmentalism and social disruption on a global scale. His travels have taken him from Guyana to Chernobyl, Louisiana to the Caspian Sea, from the Congo to Azerbaijan, and he doesn't shy away from taking a controversial stance on many of the sights that he has witnessed. In Zimbabwe he takes a sympathetic approach to the plight of the white tobacco farmers who lived under a reign of terror for many years and lost lands that in some cases had been in their families for 300 years.

"I'm not politically correct," he explains, "I pride myself on not being politically correct and not shying away from issues. I was there, I photographed it, and it was very dangerous at the time because they tried to kill white journalists. In a way I felt for these guys because a lot of them were not really that rich but just renting the farms. Zimbabwe hasn't profited from (the) elimination of the white farmer because it ruined the economy and as a result a lot of people (are) paying the price. There are all kinds of different vanishings, and this was one of them. I'm not making any judgment, good or bad; it's just a fact."

It is not only in the developing world that Kratochvil sees valuable assets being eroded. One of the chapters in the book is devoted to New York after September 11th, 2001. The vanishing here is of personal freedom in the cause of national security, and to the former citizen of a police state it brings back unpleasant memories, as well as frightening predictions. He describes the pictures in this section as "a sort of abstract take on what I feel that is going on in this country, the vanishing of our civil liberties and guarantees of civil rights. Because of the Patriot Act and the subversion of the Constitution they are really under threat, and to me it's the biggest loss. I came here from a police state, and I grew up in a police state under Stalin. I've lived through all that and I'm very sensitive to the issue. I can recognize it where most people in this country can't because they didn't have that sort of experience. I did and I can see how dangerous it can be if you don't pay attention." He is convinced that when there is another major terror attack on the United States "the whole thing's going to go down the tubes, I can tell you that. It's going to be exploited by the right-wing politicians and the religious zealots into their way of seeing America. It's very dangerous because it's a very mighty country."

The photographer also talked about the frustrations of trying to get his message out effectively. Although much of the work appeared in magazines before being collected into a book, even in these outlets, such as The New York Times Magazine, Audubon, Natural History and Mother Jones, he's getting the attention of people who are already paying attention. Still, he's philosophical about it: "When I put the book together my audience is limited, but nevertheless it's an audience. Sure I would like to get on TV and address these issues, but maybe the networks are not particularly interested. I know my limits and I just do the best I can but I can't stay silent."

The real challenge, he feels, is breaking through the barrier that exists between the two coasts and the heartland. He recalls a reporter with whom he worked in Iraq, who, upon his return to the States, was offered several lectures at various universities to talk about his experiences there. However, when they found out that he was a unilateral - an independent observer not embedded with the U.S. armed forces - every invitation was withdrawn. The offers that Kratochvil himself gets to speak are at places such as the Center for Photography at Woodstock, or the Griffin Museum of Photography in Boston. "You can go and talk to an audience and reinforce their beliefs but you're talking to the converts already. If you try to get to the heart of the problem you won't get a forum. You can't be a street preacher, you know."

Kratochvil is passionate about his subject, and given the time and energy that he has put into the production of this collection of photographs, it is clearly vexing to him that the number of people they will reach, let alone influence, is so small. Why does he continue to do it? His answer is simple, "I'm an Aries. We like to run against the wall and hit it." Apart from his 'any audience is better than no audience' attitude, a deeper answer lies in his relationship to his twelve-year-old son Wayne.

He tries to practice what he preaches, not just because he feels it's the right thing to do, but because he doesn't want to devalue his own work. It's important to him to set an example, and one way he does this is by refusing to do any high-paying commercial work that would compromise his beliefs: "You talk about being against tobacco and then Marlboro comes to you and commissions an ad for $100,000. Most people would say, "Oh shit, man. A hundred grand. That's what I make in two years, and I can do this in a week" and there's the temptation. You have to say 'no' otherwise what you do is bullshit; you're not better than the rest of the world. I'm not saying I'm a white knight on a horse, but you have to have some integrity, because your audience will find out that you're basically bullshit, so they walk away and your work would be diminished. You have to set an example; I think it's important."

Although he initially made a commitment in the early '80s not to allow money to be the overriding motivation in his work, many of the examples he sets today, refusing to own a car being one, are done more for the sake of his son than his audience. He talked about his legacy to Wayne:

"I can't leave him a green planet because I know I don't have the power but I can play a part in his social conscience about the environment. I can leave him the social thinking about continuing the fight, because it will never end. It will always be an issue, and will be something to fight for, because otherwise this planet will eventually just be a piece of rubble, and then there's nothing to fight for. So I'm hoping he can pick up the fight in his own way. He can have a good set of values; that's what I want to leave him."

There are some bright spots in the picture, some gains towards a saner way of living on the earth. Six months ago he went back to the devastated forests in Bohemia that he photographed in 1989, and was pleased to find a transformation as a result of the collapse of communism and the influence of the European Union. Air pollution has been reduced by 80 percent, and there has been extensive re-cultivation with the planting of shrubs and birch trees. He has done an essay about this revitalization that he calls Metamorphosis, and which can be seen at http://viiphoto.com. However, even a modest victory such as this cannot be viewed as complete as he explains: "For me it was still kind of tragic because I knew that nature comes back. I saw that in Chernobyl; nature's beautiful. But the people will not come back and neither will the culture or the original environment. It's just like a prairie there now because they destroyed the towns and the way of life. It's like Potamkin Village; it looks better than it used to but the earth is poisoned underground and the water is poisoned underground, and the culture is gone, so there's a tremendous loss."

He realizes that the message of Vanishing is bleak, "This is the most depressing book yet. When I got a copy from the publishers I said, 'Most depressing yet!'" But he firmly believes that if we don't face up to the problem we will never find, let alone apply, the solution. It is with resignation but without despair that he says, "Hopefully people will buy the book and look at it and pass it onto their friends and show it to their kids, or forget it and leave it in the toilet and somebody else will come along and read it. Maybe that way we'll make a little difference, so it's not forgotten. It just that it's so fucking limited."

© Peter Howe

Executive Editor

|

||||||||||

Back to May 2005 Contents

|

|