|

| ||||

UT Katrina Coverage

|

|

|||

|

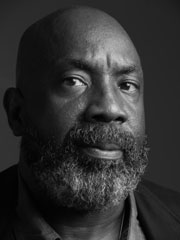

Eli Reed, Magnum photographer and now a professor at the University of Texas, Austin, had no thought of making the coverage of Hurricane Katrina's aftermath a class project. He was preoccupied with his syllabus and starting his second semester as an academic. On his way to his office, however, a student's mother approached him with her worries.

He, himself, felt as if he were a parent whose children were about to run headlong into the real world with all its dangers. He had tried, along with Professor Donna DeCesare, to prepare the students for the realities of working. But now that instruction felt incomplete. Other students, Sloan Breeden, Anne Drabicky, Meg Loucks, Mark Mulligan, and Rob Strong would soon follow Ben to cover the aftermath of the storm.

Those students now called Reed to discuss procedures and methods for their coverage. He knew and worried that they were flexing their journalistic wings by moving into unknown territory.

The coming days for Reed were a swirl of class work, lectures, Katrina, Rita and worry with little sleep. He was also proud of his students and their indomitable spirits.

They all eventually went back to Austin as working members of the press, having witnessed and reported on a tragedy. Mike Mulligan, a student, said that he had learned more in two days than in two years in school. He had combined what he was taught with what he experienced.

Reed felt fortunate to have worked with these young men and women who had made their leap into the void. They had chosen to go with or without permission.

The group made some extraordinary photographs under very difficult conditions. Some of the images were published in a weekly national magazine. In this rare circumstance, some of Ben Sklar's enterprising images were represented and selected by Magnum Photos on the Magnum Web site.

The students are continuing the work knowing this is only the beginning. They are passionate about this path and committed to making a difference in the world. For speaking with their hearts as well as their brains, Eli Reed salutes them.

For more on Eli Reed see: www.magnumphotos.com, digitaljournalist.org/issue0007/erintro.htm and digitaljournalist.org/issue0503/magnumstories.html .

By Sloan Breeden

Four days after Hurricane Katrina struck the Gulf Coast I awoke with butterflies in my stomach and a sense of urgency. Forgetting about the responsibilities of school and work, I stocked my car with water, food and cameras, and headed east.

What I found, what I saw with my own eyes in Mississippi was an apocalyptic degree of destruction. The only comparisons which suffice are the pictures I have seen of Hiroshima or Dresden. Even now I find it difficult to describe. Entire neighborhoods of houses, block after block, were obliterated, cement foundations the only trace of antebellum mansions that once lined the bay.

I arrived with another photographer, Mark Mulligan, in Bay St. Louis, Miss., at dawn on Sunday, September 4th. One of the first places we stopped was a middle school in a neighborhood slightly spared from Katrina's full destructive force. There, in the bleachers overlooking a basketball court, people were beginning to stir: sitting up on their blankets to smoke a cigarette, wandering over to the fire escape to breathe in the morning air. A bearded man moved slowly, deliberately with the dazed shuffle of a sleepwalker. Five days after Katrina struck their small coastal town, the feeling of trauma was still tangible, hanging low in the air, a cloud of silence and uncertainty.

Where was the relief? Downstairs, a man was serving food that had been liberated from the school cafeteria. Residents of the neighborhood had broken into the building a day after the storm to feed and shelter a growing number of people. This was indicative of the resourcefulness and compassion I encountered time and time again in Mississippi and New Orleans. Here was another case of people doing what had to be done to survive.

For over an hour I spoke to people in the school, sitting with them and listening to their stories. I could not have anticipated the degree of openness they showed me. I found myself surrounded by individuals whose homes and possessions had been swallowed by Katrina, who had lost everything but were anxious to share the most intimate details of their lives and experiences with a stranger. It was an incredible privilege.

I made only 10 pictures at the middle school. My first inclination was to listen and be a human being. In order for me to work, to show people outside of the Gulf Coast what had happened, I needed to first connect with the vast spectrum of human emotion which I encountered there. As a journalist I understand the need to detach yourself from the story you are covering for objectivity. I truly believe that photography can change the world. Sometimes, at a certain moment, though, it is just better to give someone a hug or help to carry the water.

More than anything else, the experience illuminated the great resiliency and inherent good of mankind. Reports emanating from television and other media sources had painted a grim picture of the situation. I had absolutely no idea what to expect. For every story of looting, failure or negativity, I found 10 which reinforced an admiration for my fellow man.

What did I learn? Besides the obvious logistics of working through fatigue and in extreme circumstances, the experience of covering Katrina reinforced my commitment to devote my life to concerned photography. I think that a crucial component of making powerful images is being able to truly empathize with the individuals you photograph. In that sense, I learned more on the Gulf Coast in two days than I could have in a year of lectures or projects.

Sloan Breeden is a second-year graduate student in photojournalism at the University of Texas at Austin. After finishing this year, he is planning to continue working on his thesis project in the Nu River gorge in China's Yunnan province. Eventually he would like to pursue a career in concerned documentary photography, focusing on conflict and poverty.

By Mark Mulligan

Around 5 a.m. on the morning of September 4, Sloan Breeden and I drove down into Waveland and Bay St. Louis, Miss., completely unaware of what to expect. What I saw and, more importantly, the people I met and spoke to changed my life, my outlook on photography, the way I shoot, the way I listen and communicate; it changed everything.

I don't know why I went. It just seemed important to be there, to experience something that was completely outside of my own experience. And, that's what I got.

Devastation. Unbelievable devastation. Street after street, neighborhood after neighborhood completely leveled. Wreckage everywhere. The idea of recovery seemed an almost impossible task. Where could it even start? Bulldozers and body bags seemed the tools most suited to the task.

But then, amid the wreckage, in parking lots and school gymnasiums, I began meeting the people, listening to the most amazing stories. I saw people in deep shock surviving only by instinct - not like animals though. Instead people were at their finest: helping each other, sharing what they had, caring for those around them, performing impossible, selfless acts for each other with little regard for themselves.

Immediately my cameras became secondary - only after standing there talking to people would I suddenly realize that I had this camera at my side and I had a responsibility to do something with it: to show people what I was witnessing and what was happening to these people. To show who these people were, their faces, names and lives. I learned the importance of a handshake, a hug, real sympathy shown in one's eyes - how translatable one's innermost feelings and thoughts are through these simple, wordless gestures. It was all stuff I'd heard before but never understood until now. I learned about humanity and what it is to be human.

I am a student. I had never experienced anything like this. I was green. A lot of people would say I shouldn't have been there. But I was, and it was unlike anything I'd ever seen. This is what I want to do.

After spending a day in Bay St. Louis and Waveland talking to so many incredible people, hearing their stories, having them openly share their lives with us, we left. My opinion on humanity changed towards the positive.

The next morning we traveled to New Orleans. Working our way from the west bank into the city, Sloan and I encountered a completely different set of circumstances. I can't imagine what the city must have been like just the day before, let alone five days before. When we got there it was simply a wreck.

I had never actually been to New Orleans before that day, so that is now what New Orleans looks like to me: empty except for soldiers walking the streets, filled with garbage and mud, water lapping up the streets.

Thanks to a New Orleans police officer's interest in photography, we ended up in a helicopter. Seeing it all from the air was a completely different experience - so surreal. I found myself just taking pictures, not even really registering what I was seeing until I went back and looked at the pictures later.

We left that night low on gas, messages on our voicemails saying that the university did not understand what we were doing and could not excuse any absences. We drove all night back to Austin.

We had slept an hour along Highway 71 until the sun rose. The whole experience hit me like a brick wall when I woke up and drove that last hour to Austin. I was listening to NPR talk about the hurricane. A sound byte played of President Bush saying something about a "tidal wave of compassion." A "tidal wave"? Anger swept over me. Who would write something like that? They must have patted themselves on the back for being so cute. I was appalled, ashamed, saddened. The adrenaline was gone, replaced with reality.

The guilt hit me next. What ultimately has stayed with me, becoming my driving force, was that I realized the responsibility I had to tell the stories of the people I had met, to show people what I had seen, to make people feel what I felt. I thought about how far my photographs were from doing that, how far I was from succeeding. I remembered that I wanted to be a photojournalist because it was a way to make people feel something beyond themselves and their own experiences. I wanted to make pictures which had that affect on people that so many great photographs had on me - that emotional response, that desire to do something, to create change, to make a difference, to understand, to question. I failed to do so. I am not there yet. I am so far from that. I felt that I had let down everyone who had shared his or her story with me. I had a responsibility to the people I had met, and I had failed to meet it, I couldn't meet it - I lacked the skills.

I've had a fire lit underneath me ever since. I've realized how hard I need to work, how focused and determined I have to be to succeed - to be that kind of photographer.

Mark Mulligan is a photojournalism and, despite what you just read, English senior at the University of Texas at Austin. He spent the summer performing Shakespeare in the Texas countryside and was in London when Katrina hit. He is interested in concerned photography and hopes to continue newspaper work, possibly in rural areas, and perhaps, go overseas after graduation in May.

By Anne Drabicky

I went to Houston when it seemed like no one else was covering the evacuees who'd been transported there. I had a place to stay, with my own bed and shower. I didn't have to wade through toxic water; there were no dead bodies and no one shot at me. For a while, this made me feel like I should have tried harder to get into New Orleans, like I wasn't a real photographer unless the situation was more uncertain. But I've realized that it doesn't matter where we ended up as photographers; the stories of Hurricane Katrina evacuees were everywhere and they are stories that are all worth telling.

While I was in Houston I met 30-year-old Desireé Singleton, who, along with her three sons, two sisters and a nephew, had been rescued by a helicopter from her rooftop. Her husband was left behind, as helicopter crews made the women and children rescue priorities. When I talked to her in Houston, she hadn't seen her husband in almost a week.

"Everyday they say, 'I want my Dad. Where is my Dad?'" she said of her sons, Marlan, 11, Jayson, 6 and Jacob, 5. "I'm trying to be strong for them, but sometimes I break down."

In November, Desireé and her husband Jonelle Singleton Jr., 28, will celebrate their seven-year wedding anniversary. "Seven years, seven years...," she said, trailing off, "and he doesn't have his ID or nothing. I can't get any phone service. He should have come by now, he should have come... I'm just hoping and praying."

The people I met in Houston, though dazed and anxious, were mostly happy. They were happy to be out of the hell of the Superdome, off the tops of flooded houses and out of the cramped and sweltering buses that eventually transported them from New Orleans to Houston.

The woman I remember the most from my time in Houston was someone I didn't even get the chance to talk to. As I was talking with Desireé and her family members, a woman came jogging through the arena shouting a family name. She was exhausted and her voice was hoarse and desperate from yelling and searching for so long. Desireé and her sisters watched and shook their heads, "Poor thing," they said, "poor woman."

As a student journalist, I went to Houston with no real agenda but to see what I could see. I wanted readers to remember that the story wasn't confined to the chaos of New Orleans, but that a city only three hours away from Austin had welcomed 14,000 people whose stories needed to be told, too.

These are stories that will continue for a long time, and these are people with whom we will become familiar. Desireé and her family couldn't leave their homes because of financial constraints. They're not alone in their situation, but just because their story is a common one doesn't mean we should value their words any less.

I went to Houston because I could get there, cover a story and not get shot at. I left Houston understanding that the place is irrelevant in the face of the story I was lucky enough to hear and document.

Anne Drabicky is a second-year photojournalism graduate student at the University of Texas at Austin. She covered the stories of the Houston evacuees for the university's student newspaper, the Daily Texan. Prior to returning to school, she worked for four years as a designer at the Fort Worth Star-Telegram. After graduation, she hopes to find work as a documentary photographer.

By Meg Loucks

We drove to the Gulf Coast of Mississippi 10 days after Hurricane Katrina hit. The story in the Gulf had transformed a week and a half after the storm. New Orleans had been evacuated, the National Guard was protecting residents in neighborhoods all along the coast and homeowners were slowly beginning to pick up the pieces of their lives.

Eli Reed had briefed me the night before we left. Another professor, Donna DeCesare, had called and told Eli that a journalist had just been shot in Baton Rouge in his car. He was worried about sending his students into what he thought looked like a war zone. But we packed our gear and headed toward the Mississippi Coast - not sure what we would find or where we would end up.

We made it to Hattiesburg, Miss., around 9 p.m. We had planned on staying at the local paper, but couldn't get access once we arrived. The town was packed, so we camped out in a parking lot. Hattiesburg didn't appear to have sustained much damage, but hints of the hurricane were everywhere. Residents and refugees quietly told hurricane stories and Hummers zipped down local streets.

The next morning we made our way down Highway 49 toward Gulfport, Miss. We knew that the border between Louisiana and Mississippi had sustained the most damage from Katrina's wind and rain. We thought Gulfport would be a good entrance point.

As we passed through Gulfport we began to see the first signs of Katrina's wrath: Gas stations folded into piles like a stack of playing cards, grocery stores boarded up and residents in ragged clothing sweeping up glass and debris.

The neighborhoods south of the railroad tracks in Gulfport were like another universe. I had never been to Mississippi before, and I couldn't even begin to imagine how this massive pile of destruction had been a neighborhood--how anyone had ever lived here. From the outside, it looked like there was no remnant of human life left.

We drove in - dazed. The beach was obliterated. Barges sat in neighborhood streets. Semi-trucks were totaled and wrapped around trees. The barges had been emptied of their contents by the force of the storm and two-ton rolls of paper; stacks of lumber and frozen meat were strewn across the neighborhood. It was a wasteland of plastic, rubble and sewage. The houses that were left standing had been marked by officials with spray-painted symbols, which represented the number of victims found and the date the house had been inspected.

We stayed in Mississippi for three days and after the initial shock of that first impression of Gulfport, the details of the destruction I saw turned into a blur. But the people haven't left me. They remain seared into my memory.

The neighborhoods appeared vacant, but once we parked the car and began to shoot, I saw that life had continued on. Some of these communities had three generations of family members that had survived other storms and had stayed through Katrina. They were determined to rebuild their community - even if they had to start from scratch with everything working against them. If FEMA didn't show up, they still knew they had their community of friends and family.

The National Guard and a host of volunteer sheriffs and nurses made rounds passing out necessities, but what seemed to keep these people going was the future. I found it amazing that in a world that looked as though it had been turned upside down locals could talk about what the future held for them.

I shot less in those three days than I ever have. I have grown up with digital and I've never been hesitant about shooting before. But I learned something about listening to others. I began to understand the difference between when I can help someone with my camera and when I can help as another human by listening.

Meg Loucks, 25, is a second-year graduate student in the photojournalism department the University of Texas. She will graduate in the spring and will be looking for a newspaper position.

By Rob Strong

This June, in preparation for a trip to India and Nepal, I got all my shots for hepatitis, tetanus, and other tropical diseases, and braced myself for extreme poverty and widespread civil unrest. The closest I would end up coming to martial law and infectious disease this summer would be 500 miles away in Louisiana and Mississippi.

Ten days after Katrina hit, I drove out to coastal Mississippi with photographers Meg Loucks and Megan Griffiths. While we were prepared with essentials like food and water, none of us had any experience with an event remotely like Hurricane Katrina.

During the time we were there, the humanitarian crisis in Mississippi was largely under control. The National Guard had secured the evacuated neighborhoods to prevent looting, and the Red Cross and other agencies were distributing food, water and clothing to those in need. Some residents were already in the process of raking the debris of their neighbors' houses out of their front yards. However, the physical scars to the coast were astounding.

When people say that buildings are gone along the Mississippi coast, it's not a figure of speech. It's hard to get this across in photos, but entire cinderblock structures (a Days Inn, a Waffle House) were reduced to flat cement. Even the rubble was gone. The only clue that Gulfport was once a pretty seaside city with hotels along the boardwalk were concrete slabs with small rectangular sections of blue tile every 8 or 10 feet, which after a moment I realized were the bathroom floors of beachfront motels. I've never been to a war zone, but the combination of utter destruction, military Humvees tearing along the sand, and helicopters rushing overhead gave the impression that I was in Mogadishu or Mosul.

A mile-long peninsula sticks out into Gulfport's bay with a commercial shipping dock. Until recently, the dock was full of shipping containers, semi-trailers, huge pallets of stacked lumber, 5,000-lb. rolls of brown paper, and great spools of cloth. Katrina's storm surge picked all of these items up and hurled them a mile across the bay and into the hotels and residences of the town. A sailboat sat in an apartment building and a 50-foot steel flatbed trailer was wrapped around a tree like taffy. Shipping barges and floating casinos sat in residential neighborhoods like alien craft.

In Bay St. Louis, a few miles toward New Orleans from Gulfport, there was a tent city set up at a Wal-Mart about a mile in from the ocean. I asked a relief worker there if the parking lot had flooded during the hurricane. He said it had; they weren't sure exactly how deep it had gotten, but a rough indication was that they had found eight bodies on the roof of the Wal-Mart after the waters receded.

I had very little difficulty photographing in this situation: every five minutes, I saw something that would have been the most remarkable thing I saw all week, any other week of the year. The security forces in charge of the area, including sheriff departments from as far away as Missouri, were generous not only with access to affected areas but also their own food and lodging, providing us with a place to stay in Gulfport. The residents affected by the storm seemed genuinely pleased to speak to journalists willing to hear their stories. (There was a sentiment among some in Mississippi that the damage to their region was being ignored by the press in favor of the flooding in New Orleans.)

On our third day in the area we were driving down the beach road and wondering if it was worth getting out to shoot some more of the devastation. As we passed dozens of demolished houses, I said (without irony), "Oh, I don't know, I'm tired. Let's only stop if we see something completely unbelievable." After a beat, we immediately realized how absurd that statement was. It was a testament to how overwhelming the landscape was that in only three days, we had become totally accustomed to seeing home after home destroyed by a 25-foot wall of water.

I feel very lucky that I was able visit this traumatized community and make some pictures which help to convey the experience of the residents of coastal Mississippi. The trip pushed me in my photography and strengthened my commitment to a career in photojournalism. I am also extremely grateful that I have professors like Eli Reed who have been supportive of my work and that I work for a newspaper, The Daily Texan, which has the resources and confidence in me to send me to events taking place on the world stage.

Rob Strong, 24, a second-year graduate student at The University of Texas at Austin, will graduate with a master's degree in photojournalism in May 2006. He has a bachelor's degree in computer science and economics from Dartmouth College. He is originally from Wayland, Mass. Rob can be reached at rob.strong@gmail.com.

By Ben Sklar

Monday, August 29, 2005, 9 p.m. at the Emergency Management Agency, Bay St. Louis, Mississippi

I just got in from covering the disaster, and in reflection I realize I could have been dead and no one would know. It's a terrifying thought, but very true. I can't believe I ran out during the storm to photograph those people on their car. (I really wasn't thinking ... I just reacted as the current overpowered the Suburban.) At last we're all safe. There is no communication with the people outside the room I'm in. The people have been more than helpful and overly friendly. I gave a 15-year-old boy, Colby Taylor, some shoes and clothes and told him to keep them. The little girls (7-year-old twins Jordon and Jody) used my horse blanket after they were rescued and cried their eyes out all over it. I can't imagine screaming for help on top of a Suburban logged in a ditch with a river of flowing water surrounding me during the biggest hurricane in history (I guess that's what I did). I haven't eaten in over 12 hours, had little to drink, haven't used the bathroom (what would add up to 5 days total) and absolutely no communication. I want to go home tell my mom I love her, hug her and eat at El Sol y La Luna. More importantly, I need to find an Internet hookup so I can get my photos on the wire. I've been a witness to so much spot news it's sickening. The beach looks like a war zone, all the bridges are out, roads destroyed. Like nothing I've ever seen. The world needs to see this, these people need help. The back window on my car busted around midnight so I moved my car to the side of the building during the storm. My whole life is in the jeep and now it's all wet. After the storm calmed and rain stopped we rode in the back of a jacked up truck and saw the devastation. There is flooding everywhere, looting damage, cars on top of each other, people on roofs. The EMA got a call about some burn victims and we rushed out there. It was far past Waveland and took nearly 45 minutes to get there. On the way we hit a dog crossing U.S. 90 with its family: A young single mom, and her 3 kids. We were going around 80 and couldn't stop, we hit the second dog to cross the highway. I heard the loud thud as we ran over the bulldog, the woman screamed no and fell to her knees in the street, one of her sons, a very young, and confused boy ran up to his former best friend who lied in the street as the dog raised his right arm limply. Al Showers the TV guy trapped with me, didn't turn but winced when he heard the scream. We got the burn victims, whose house exploded, I photographed them in the back of the truck on their stretcher cots with charred and bubbling skin. The floors got flooded last night, I was lucky to be able to save my computer (I mac desktop). The wind has died and hopefully I'll be able to transmit soon, realistically tomorrow. I've thought a lot about how I wanted to change the world with my work and I think I will today. Does this event justify my level of photojournalistic skill? The devastation is unreal, I can't stop thinking about it. It's like the last 2 days have been a dream. I can't believe how this happened. I'm hungry, tired, dirty, smelly, but all I care about is this story and my mom. I hope she's not crying and knows I'm safe. I feel like a veteran disaster photojournalist and hope I can tell the story and more importantly the story of survival of these people.

Ben Sklar started using cameras at age 12. For most of his life he's lived in Austin, Texas. Currently he is a senior at the University of Texas studying photojournalism. He plans to pursue a career in photojournalism and says his plan is to use his "vision, skill and knowledge to make beautiful pictures to help change the world for the better."

© Marianne Fulton

Senior Editor

Dispatches are brought to you by Canon. Send Canon a message of thanks. |

||||

Back to October 2005 Contents

|

|

Katrina Statement

Katrina Statement

Katrina Dispatch

Katrina Dispatch

Katrina

Katrina

The Aftermath

The Aftermath

In Mississippi

In Mississippi

Journal entry

Journal entry