|

→ November 2005 Contents → Feature

|

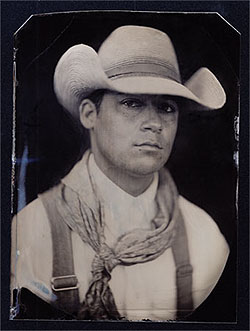

Tintype Cowboy

|

|

|||

|

I suppose if you're a National Geographic photographer who was born in Spur, Texas, and graduated from Hereford High it's almost in your DNA to photograph cowboys. It is more unusual, however, for anyone in this age of defining technology to photograph them using a technique that was in its prime almost 150 years ago. Robb Kendrick recently authored a book called Revealing Character, published by Bright Sky Press, which is the result of doing just that. He traveled around his home state with an old view camera, a set of antique lenses and two portable darkrooms to produce a series of tintype portraits of this enduring breed, whose survival defies the trend to replace agricultural workers with machines. The process used to make a tintype is complicated and hazardous, and one that would probably not meet with OSHA's approval. There are two stages in the procedure: first of all a piece of tin has to be blackened through a process called japanning. This is achieved by mixing asphaltum, Everclear (a grain alcohol so strong that it is illegal in some states) and ether, and bringing the concoction to a boil. Should the photographer survive this hazardous alchemy, the ensuing solution is painted onto silver tin plates and cooked in an oven box to stabilize it. Once this part of the process is complete, and it can take several days to prepare 100 plates, the intrepid tintype artist can venture forth to the shoot. This is where the two portable darkrooms come in. Kendrick has one for remote locations that is 3 feet by 4 feet with no ventilation, and a more commodious version, a trailer, 7 feet by 12 feet, with a heater and air conditioner as well as a 40-gallon water tank. It is his version of the horse-drawn darkroom that Roger Fenton used during the Crimean War, and which frequently came under Russian cannon fire, being mistaken for an ammunition wagon. When the camera is in place in front of the subject the photographer has to then coat the japanned plates with collodion, a mixture of gun cotton and ether that is commercially available through medical supply houses because it is used in the treatment of burn victims. The coated plate is immersed in silver nitrate and placed in the film holder. It has to be exposed to light immediately. The leeway available depends on the temperature and humidity of the location. In a summer desert you have about six minutes to make the exposure, a time period that increases to a maximum of 20 minutes in a humid area like Louisiana, especially in the cooler temperatures of the winter. Once the exposure has been made the plate has to be developed immediately. For a slow process there's a lot of immediacy, and it requires very patient subjects prepared to sit there while the photographer dives in and out of the darkroom. It also demands that the subject stays very still for exposures that average from two to seven seconds, an accomplishment that is easier for the cowboys than for their horses.

Kendrick learned the technique from an eccentric called John Coffer who lives in the Finger Lakes region of Upstate New York in a house that he built himself, but which lacks water or electricity. His only means of transportation are a bicycle or ox cart. Ironically he has his own Web site, http://johncoffer.com/, although how you do this without electricity I'm not quite sure. Kendrick had read about him in The New York Times seven or eight years ago, and had filed the piece in a folder that he keeps of "things that I find interesting and someday are going to act on." He contacted Mr. Coffer, and arranged through the U.S. Postal Service - no e-mail please - to do a three-day workshop with him. Within the first two hours he was hooked. One of the things that he loves about the process is that it brings him back to what initially ensnared him and many others into photography - the sight of his very first print emerging in the developer. Although, after extensive training, digital technology gives the photographer greater control over the final presentation of his or her work than a darkroom ever can, it lacks the magic that silver chemistry can perform. In an interesting juxtaposition of the old and the new, the reproductions of the tintypes that are for sale on Kendrick's own Web site, http://www.robbkendrick.com/, are digital prints from copy files that he makes on a 4 x 5 digital back, thereby encompassing the two poles of the past and the future, although some would say the birth and death, of photography. A question that has been posed many times to Kendrick by people who have read the book is, "Who did the styling?" The answer, of course, is "Nobody." The cowboys were photographed in what they happened to be wearing that day, and pretty fancy some of it is to be sure. A lot of cowboys don't own much, mainly because they don't get paid much - about $1,000 a month on average, according to Kendrick. But most of their living expenses are taken care of, albeit in a fairly basic way, so a lot of their money goes into their gear, whether it is their hats, boots, saddles or spurs. The photographer believes that this is more from pride than vanity, and an acknowledgement of their roots in the Mexican cowboys, or vaqueros. In fact there is a sub-sect known as Buckeroos, a derivation of the word vaquero, found in the Great Basin Area of Nevada and Oregon, who make their Texas brethren look downright dowdy. Dressing well is known as "looking punchy," and if you want to know what punchy looks like go to the Working Ranch Cowboy Association World Championship Rodeo held in Amarillo, Texas, from Nov. 6th to the 13th. You'll find Kendrick there, but he'll look more like a farmhand. One of the strengths of photographing this subject using the tintype technique is that it provides a perfect confluence of timelessness - that of the occupation, the clothes and the photographic presentation. All of the pictures in the book could have been taken at any point over the last 150 years, and it powerfully expresses the sense of tradition that is so important to the cowboys. However, a weakness of this archival process is that at the same time it portrays a very romantic view of what is a relatively small sub-section of agricultural workers, and perpetuates an American myth that, given the present occupant of the White House, causes considerable discomfort to a lot of their fellow countrymen and women. One reviewer unflatteringly compared it to Avedon's American West, which he found more relevant to the world as it is today. This kind of comment doesn't faze Kendrick at all. First of all he sees only a superficial connection between the two books, his agenda and Avedon's being completely different. He took the pictures because he finds the cowboys interesting and admirable. They work 80-hour weeks, not for overtime but because they love what they do, being outside and on horseback. They are also fiercely independent and self-sufficient. One of the ranches where he shot covered 563,000 acres, or 900 square miles, and was worked by only 28 cowboys. Each had responsibility for one section, and so in a way each had his own ranch. Despite their inevitable isolation he found them interested in the world outside of their own, and considerate of opinions with which they didn't necessarily agree. As he puts it, "Their respect is yours to lose." As he was talking to me I was struck by the parallels between the photographer and his subjects. Working long hours away from home for very little money but because you love it and like working outdoors, and steeped in a sense of tradition, this describes photojournalists and cowboys equally well. Maybe that's why there is a renewed interest by many photographers in the old archival methods, because these techniques bring us back to the roots of our craft in an age of digital automation. Maybe for some of us the tintype, the ambrotype and the platinum print are to photographers what hand-tooled saddles and elaborate spurs are to the cowboy. Or maybe I'm just being romantic. Purchase Revealing Character at Amazon.

© Peter Howe

Executive Editor

|

||||

Back to November 2005 Contents

|

|