|

→ February 2006 Contents → Column

|

A Bird's View of History: The Digital Camera and the Ever-Changing Landscape of Photojournalism

|

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

Someone once said that it takes at least 25 years for the historical significance of anything -- a war, natural disaster, or an invention -- to be fully appreciated and understood. Digital technology has been influencing photojournalism for decades. Looking back at the short but remarkable history of the digital camera helps us to understand how technological advances are redefining the field of photojournalism.

The digital revolution in photography began when Kodak, Canon and RCA were all researching the possibility of converting light into digital images in the 1970s. Inspired by technological innovations in television photography, some still photographers started to explore the possibilities of utilizing video and electronic imagery in photojournalism. In 1979, National Geographic photographer Emory Kristof was the first to use an electronic camera while photographing life at the bottom of the ocean in a miniature submarine.

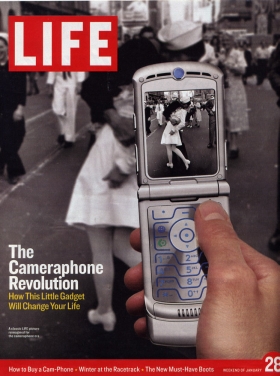

In 1981, Sony heralded its Mavica non-film electronic camera as the "camera of tomorrow." Writing in News Photographer in 1982, Ed Breen contended, "When the electronic camera, and all that goes with it, is finally in our hands -- and it will be -- it will not be because we have sought it out, but because we are no longer left with a choice." During the 1980s, digital imaging technology became an increasingly pervasive force in news operations. Advances in telephony and computing accelerated the pace of change for many. By 1984, photojournalists were already experimenting and using cellular telephones to send images from remote locations through drum transmitters.

In 1984, Ralph Langer of the Dallas Morning News commented, "It sounds like it [the digital camera] could give us more speed, more time to do the selection and cropping of photographs and less time just doing the technical production of it." Photojournalism educator Charles Scott noted, "Electronic photography is going to replace the silver image. We are going to have to have an understanding of how to edit pictures, how pictures are stored electronically and how to edit them electronically."

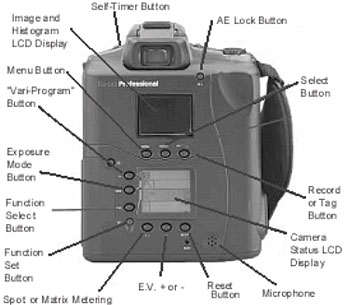

The first professional digital camera systems were introduced to photojournalists in the early 1990s. Mary Bellis, author of History of the Digital Camera, recalls that "in 1991, Kodak released the first professional digital camera system (DCS), aimed at photojournalists. It was a Nikon F-3 camera equipped by Kodak with a 1.3 megapixel sensor."

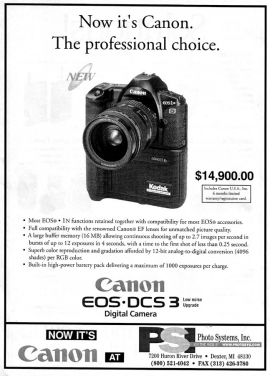

The Digital News Camera (NC2000), based on Kodak's Digital Camera Systems (DCS), made its official debut in 1994. The NC2000 was co-developed by The Associated Press and Kodak specifically for photojournalists. The camera was lighter, used standardized lenses and could make as many as 700 exposures at a time. At more than $15,000 per unit, the NC2000 replaced an earlier model, which required carrying a battery shoulder pack. The high cost of the camera as well as issues associated with image quality and file preservation, were significant factors in the adoption rate of the digital camera into photojournalism.

By 1996, more than 85 percent of newspapers reported that computer skills were either somewhat or very important in the hiring of entry-level journalists. One photographer, in a 1998 News Photographer article about the benefits of digital photography, suggested that the digital camera "gives you a lot more opportunities to shoot ... and the photographer also can spot-check work on an assignment." The speed in which photographers have adapted to the digital cameras differs from past experiences such as adapting to 35mm film cameras. In the case of the latter, more than two decades of transition time allowed photographers to become accustomed to the smaller camera and format size.

Today, however, with the cost of digital technology decreasing and image quality increasing, the history of photojournalism is being redefined. Today, professional digital cameras range between $1,000 and $5,000 and are considered technically far superior to previous models just five years ago. For example, Kodak's latest DCS Pro SLR/n models offer the highest resolution on a 35mm format at 13.89 megapixels with an image resolution in the 4,536 x 3,024 pixel range. In addition, Nikon and Canon both released newer versions of earlier D1 and EOS-1D models. These cameras, the Nikon D2H and the Canon EOS-1D Mark II, are especially suited for photojournalism with faster shutter response times and longer battery life, and are capable of making 40 continuous JPEG full-resolution images at a speed of eight frames per second.

As this brief history of technological change in photojournalism attempts to explain, the speed at which images can be produced and published has been a driving factor for innovation. Until the advent of the digital camera, photojournalists defined behaviors and routines around the visual environment of working with film-based chemical processes. As Nick Didlick, a pioneer in digital photojournalism, suggests, "Anyone keeping up with the changing trends in newspaper photography knows change is happening fast ... digital photography has finally reached a stage where it is a deadline and production tool, rather than an expensive toy for computer-literate photographers."

© Dennis Dunleavy, Ph.D

Assistant Professor/Photojournalism Coordinator, School of Journalism and Mass Communications, San Jose University

|

||||||||||||||||||

Back to February 2006 Contents

|

|