|

→ May 2006 Contents → Feature

|

Coal Hollow

May 2006 |

|

|||||||||||||||

|

"If we must grind up human flesh and bone in the industrial machine we call modern America, then before God I assert that those who consume coal and you and I who benefit from that service because we live in comfort, we owe protection to those men first, and we owe security to their families if they die."

There was a time when John L. Lewis was a household name in America and news of mine disasters and miners' strikes was frequent. Where I grew up coal had a direct presence in our lives with a coal bin and coal dust in the basement. We shoveled coal into the furnace and ashes into the yard. Industry depended on coal and we knew it because when coal production stopped, industry stopped; in the worst cases it was a national crisis.

Coal is still a formidable force in American lives, but much less evident. It provides about 50 percent of our electricity and is used in making hundreds of products including cement, ceramics, wallboard, plastics, medicines and fertilizers. Sadly, mine disasters are still making news, and the families connected to coal production are still lacking protection, comfort and security.

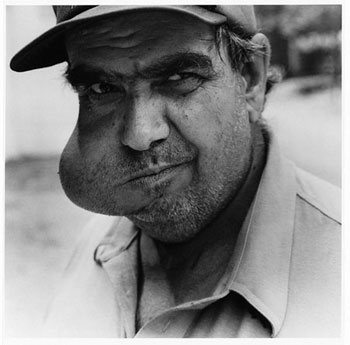

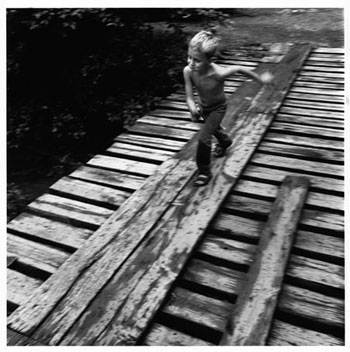

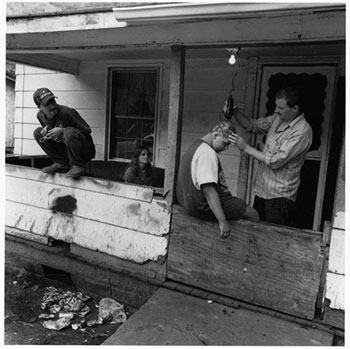

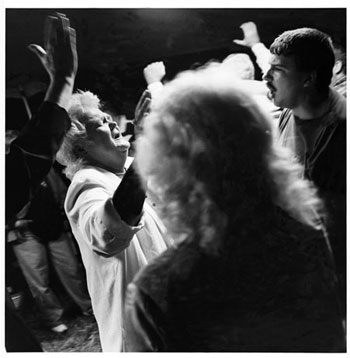

Coal Hollow, not a real place, is a construct from all too real places and people documented over several years in eight counties of West Virginia, our second largest coal producing state. Melanie Light's oral histories and Ken Light's black-and-white photography give us a documentary that goes far beyond the news to show the enduring damage coal mining has done to the people and environment of Appalachia. We should all note this degradation for, as Robert Reich, an economist, Professor of Public Policy and former U. S. secretary of labor, writes in his Foreword to Coal Hollow, "There is growing evidence that the survival of societies depends on how they treat their human and natural resources."

The introduction, "Slag," by Melanie provides an economic and historical context for the people and places we meet in Coal Hollow. It is a cautionary tale with implications for those of us somewhere in the middle class because the economic forces that enriched those few at the apex of coal production and impoverished the land and workers left behind are akin to forces playing out now in other industries of the global economy, threatening many now comfortable. Melanie concludes "Slag" by writing: "Along with mineral debris, the coal companies left behind human slag. The broken earth and the broken people await reclamation." The subsequent portfolio of photographs and interviews make it clear that reclamation will be hard to come by.

Ken's connection to Appalachia goes back to his college years at Ohio University, located not far from the region documented in Coal Hollow. Asked about a possible connection he writes, "I was a United Mine Workers poll watcher during the dissident campaign of Joseph A. Yablonski in 1969 elections, photographed in rural parts of Appalachia and in 1972 set off to rural West Virginia when the Buffalo Creek Mine disaster happened in February of that year." That disaster, one of the deadliest floods in U.S. history, was caused by negligent strip mining and killed 125 immediately, injured 1,100 and left 4,000 homeless. There was little penalty for the mining company responsible and small recompense for the towns and lives destroyed.

Melanie Light's 11 oral histories are thoughtfully chosen from about 30 interviews to "represent as complete a cast of characters as possible: retired miners, men and women who have never had permanent employment, a local coal industries owner, a justice for the West Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals, a writer who bravely ran for governor on a third-party ticket, and people who returned to the hills when their lives failed elsewhere." She writes a statement for the head of each, then gives us the speaker's words edited into a cohesive, highly readable personal statement. Her own words inform like a fine novelist. Describing Faye's grandson she writes, "…finally he does what she wants, more or less. He's 18 and wants badly to be a man but isn't at all sure how to do that." For her meeting with a novelist and political activist she writes, "Clutching a giant shopping bag, she stands uncertainly in the middle of the crowded café as if she had stumbled into the wrong universe, when, in fact, it is practically her second office."

But the jobs that remain pay reasonably well if you discount discomfort and danger. Welfare and government help for communities is seen as woefully inadequate by some and as creating a regretful dependency by others. Unions are credited with historic improvements in miners' lives, and with driving jobs away with excessive demands. The area is seen as having great potential for modernization and development by one interviewee and as hopeless by another who says, "There's nothing that would attract anybody."

A documentary that takes us thoughtfully and with feeling into a complex subject depends on artful integration of well-wrought images and text. Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, with photography by Walker Evans and text by James Agee, is a classic referred to by Orville Schell in his Foreword to Coal Hollow as he points to the importance of both the independence and integration of Melanie and Ken Light's contributions to this documentary. He quotes Agee's discussion of the ideal, a co-equal text-photograph relationship "…mutually independent and fully collaborative." Walker Evans told me the model for that relationship was The Golden Bowl, a novel by Henry James with photography by Alvin Langdon Coburn first published in 1904. Like Evans and Agee, Coburn and James were considered among the greatest practitioners of their respective arts in their own time. James discusses photography's relationship to his text at length in his introduction. Evans and Agee worked together in the field. Coburn and James did not. Balance in the design of documentary presentation and development of material in the field are separate, but related issues.

Their interaction helped both gathering material in the field and designing its final presentation. Melanie continues her thoughts with, "I feel that this project is a lot stronger because of the collaboration in many ways. Each one of us had to defend the use of any given picture or piece of text more rigorously in order to create and preserve a cohesive voice. In that process things were jettisoned or discovered that strengthened the whole project and sharpened our thinking."

Beyond its merits for helping us appreciate the personal and social burdens of coal mining in Appalachia, Coal Hollow serves as a model for how to bring photography and interviews together in a documentary book.

We no longer have a John L. Lewis. We no longer see miner's lives as a national crisis. We still have mine disasters, such as the recent Sago disaster. We currently have a national push to increase coal production because of the rising costs of oil and natural gas. The government is not inclined to do nor trusted now for more efforts like the Boone Report. News sources give us reports on dramatic events, usually with thin context. Without documentary efforts like Coal Hollow we are short of background, short of the insights we need to be informed, empathetic, fully functioning citizens.

© J.B. Colson

|

||||||||||||||||

Back to May 2006 Contents

|

|