The first person I met in Ethiopia was Abdi, a distraught father sitting beside his dead 2-year-old son. One after the other, his children had been dying because the family does not have enough food. "Now I only have two left," he says. Before the sun set, he had buried his sixth child.

|

|

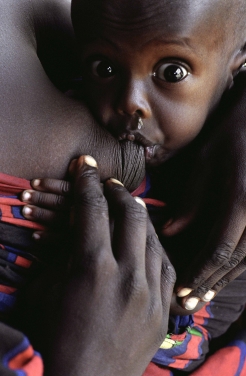

Victims Waiting For a Miracle: Exhausted and hungry families put their hopes in the hands of the Doctors Without Borders Feeding Center in El Kerre, Ethiopia, on Thurs., June 15, 2006.

Ake Ericson/WpN

|

The next morning I left the mud hut where I had been sleeping and went to the Doctors Without Borders tent hospital for malnourished children. There were mothers lying in a long row with children that needed to be fed by droppers to survive. When they finally do receive food, they are too weak to eat. The child mortality rate in southern Ethiopia is unbelievable, the doctors say. The average life expectancy in the country is 47 years.

I was there amidst so much hunger because of an advertisement in Sweden's largest newspaper. Early one morning in the beginning of June I read the short phrase, "There is a hunger catastrophe in El Wak in northern Kenya. Thousands of children are starving because of the drought." An hour later I called the MSF (Medicins Sans Frontieres) press attaché in Stockholm and asked if I could go to their feeding center in El Wak. She checked with her colleagues on the ground who said there was already a lot of press there. I was told it would be better if I could go to the Muslim areas in southern Ethiopia instead because there were no journalists there but the situation was just as bad.

|

|

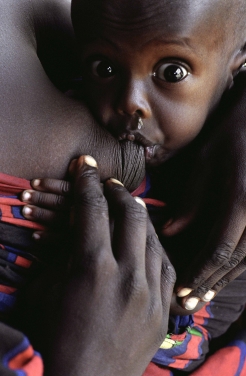

A malnourished mother tries to breast-feed her little boy, probably well aware it is more for consolation than nutrition, in El Kerre, Ethiopia, on Thurs., June 15, 2006.

Photo by: Ake Ericson/WpN

|

A few days later, I was on a plane to Addis Ababa. After landing I got four hours of sleep and then we flew on further south to Gode in southern Ethiopia. When we landed, we found that a thunderstorm had crossed over the south and the roads were more or less washed away. We were forced to change plans and go to MSF's feeding center in Cherrati that day. At five o’clock the next morning we started driving 250 km on nonexistent roads through rivers that had gone dry. It took seven hours in a Toyota Land Cruiser under a clear blue sky with wild lions and baboons crossing in front of the car. Once in Cherrati, I began taking pictures without pausing, knowing that I only had five days. There, I met Abdi in his desperation. I visited the tent hospital where the fight goes on for those who are still alive. The last morning we headed out to El Kerre, a remote village 50 km away from Cherrati. The volunteers handed out food and medicines once a week. When we finally arrived, hundreds of mothers were sitting with their starving children outside the gate waiting to be let in. The nurses measured the thickness of the children's arms to see which ones were in greatest need of the week's food ration.

|

|

Asli, 18 years old, is the victim of tuberculosis (TB) and is gravely malnourished. She lays in bed because she is unable to walk. Cherrati, Ethiopia, Wed., June 14, 2006.

Ake Ericson/WpN

|

Compared to the daily struggle for survival that I was met with in Ethiopia, the technical problems I encountered with my cameras became petty. Still, I was grateful about my choice of analog cameras since the camp's diesel generator would break down almost every night and leave us without electricity. With 44 rolls of color film in my luggage, I left the feeding center one morning to return to travel the red sand roads to the airfield where I was to fly to Addis Ababa the next morning. However, after 120 km the Land Cruiser broke down. The motor was completely dead and so was the battery, plus the COM radio was also broken. The sun was frying our heads, and the thermometer was showing 47 degrees Celsius in the shade. After half an hour we were finally able to get the two-ton jeep going.

Finally home in Stockholm after a 40-hour trip, I finally put my feature together and sent it to WpN, my agency. The war in Lebanon has just started and the media is focused solely on it. I continue to work on my daily bread and butter assignments and, yet again,

© Ake Ericson

Swedish photojournalist Ake Ericson was born in 1962. His first photograph was published when he was 14 years old. He has worked as a photojournalist since the age of 18. After 12 years of working for various local newspapers in Sweden, he was hired by Sweden's largest daily newspaper, Aftonbladet, where he stayed for 10 years.

Since 2000, Ericson has worked as a freelance photojournalist. He has been working in many eastern European countries: Russia, the Balkans and especially in the Kosovo region. He has won several photo awards in Sweden. Ericson is affiliated with World PictureNews in New York and his work has been published in Paris Match, Le Figaro, Stern Magazine, Le Observateur and Le Monde. Today he lives in Stockholm with his wife and two sons.

Dispatches are brought to you by Canon. Send Canon a message of thanks.

|