I have spent most of the past year or so photographing gypsies in a dozen Eastern European countries. An editorial grant by Getty Images allowed me the freedom to decide what kind of people to shoot and where.

|

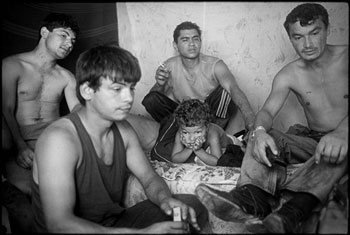

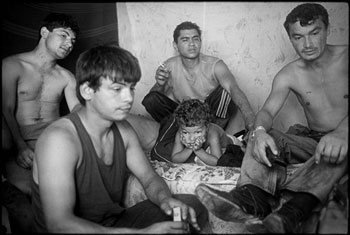

Gypsy men watch TV in their makeshift tent in the outskirts of St. Petersburg, Russia. They are Hungarian-speaking Roma from Ukraine. They often come to St. Petersburg and other big cities to collect enough money to survive the winter in their home country. They live near communal or industrial waste dumps where they collect and sell scrap metal. Photo by Balazs Gardi |

I don't plan much before going on a trip. I choose the location and the subjects but unlike some other photographers, I don't read a lot of literature or prepare extensively. We all have different methods: mine revolves around natural curiosity. I prefer to be free from other people's conclusions and observations going into a project.

In Hungary, where I grew up, as well as in most countries around Eastern Europe, the prejudice against gypsies, or Roma, is extreme and goes back for centuries. It stems from an ignorance that most prejudiced people aren't even aware of: they don't know what they don't know. The people from childhood are taught mocking rhymes, folk songs, everyday sayings, common tales, myths and even popular racist jokes.

According to the most accepted theory, the origin of the Roma people was in India and over the past few centuries, they have moved to different parts of the world. Approximately 8 million Roma live in widely dispersed communities across Europe. Historically, the largest communities are to be found in the countries on the Balkan peninsula and in Eastern Europe. Fortunately, I have been able to work in nearly all of these countries in the past year to complete my project.

|

The son of Kolaj, my host in Peri, waits for his father to return home in front of his family house in the center of the village. Following a 1956 government decree, Roma were forced to settle in one place and to start working on Soviet collective farms under police control. Photo by Balazs Gardi |

I have taken numerous photos of the Roma in a rather ad hoc way during my career. However, this current project is the first time that I have been able to systematically uncover this topic – by spending an extended period of time with these people. I have seen how harsh the fate of the Roma children is in the Bulgarian winter, when in order to avoid freezing, they have to gather wood in the forests instead of going to their poorly heated school. I have spent time with the Roma people in the refugee camps in Kosovo, discovered that they are despised and unwanted in any country, and that they still live an endlessly miserable existence seven years after the war. I attended Roma weddings, funerals, religious and cultural events and the Roma have shared their grief and joy with me and my camera. During my travels I have captured the many smiles in their grim lives, their never ceasing happiness despite their hopeless poverty, and I have experienced some of the strongest family togetherness in both good and bad times.

|

Russian Gypsy women dance in front of their house in Peri village near St. Petersburg, Russia. Ignored or despised by the rest of the population, the Roma are amongst the most marginalized minorities in Russia and have been forgotten by the international community. Photo by Balazs Gardi |

When photographing a Roma community, I try to spend as much time with them as possible, preferably day and night. I rarely use translators even in foreign countries: I feel that the bond between me and my subjects is violated when someone keeps butting in. I tend to hire interpreters only for the first day or so. I have them explain to my subjects what I'm doing, who I am, what my goals are, and then I go back the next day, alone.

That's exactly how I began work in St. Petersburg, Russia. An assistant attorney who works with the Memorial NGO took me to a village, Peri, about 100 kilometers (65 miles) from the city. Half the population is Russian and the other half is Roma. My guide introduced me to the village chief, who promised that I could stick around and work when I returned a few days later.

Three days on he was nowhere to be found. Unsure about what to do next, I began wandering around the village. A group of men sat on a nearby porch and called me over. My Russian vocabulary is limited at best but the 50 words I remembered from my studies proved enough. One of them invited me to spend time with his family. He told his sons to watch my luggage and squeezed me into his crumbling old Lada. We were off to celebrate Midsummer Night, Russian-style, out in the woods with plenty of vodka, grilled pork and singing.

|

A young Russian couple watches as their gypsy friends start fighting in the early morning during their celebration of Midsummer Night out in the woods near the village of Peri, Russia. Photo by Balazs Gardi |

My host wasted no time drinking to oblivion. His brother, after a while, removed the key from the car to prevent him from driving. Apparently, he was a dangerous drunk. Meanwhile, my host and a friend's brother got into a spat and things quickly ended in a brawl. Friends separated the two, but then my host decided he had had enough. He would drive home.

His brother tried to keep him out of his car by locking himself inside, but my host knocked the windows out with his bare hands, and dragged his brother out. I began to walk home with another guy – a 10-mile hike. A few minutes later, though, my host, with car tires screeching, pulled over next to us and demanded we join him in the Lada. He gunned the engine and zipped down the potholed dirt road at 50 miles an hour in second gear until the exhaust pipe cracked and the coolant boiled off. Dawn broke before we got home and after the others headed home, my host began to cry on my shoulder.

The next day, as if nothing had happened, he asked me giddily to tell his family how he had injured his hand and nearly wrecked his car.

This might have been an extraordinary story, but it is by no means a typical one. I've gone through a lot during the past year I spent with the Roma, and I've seen more normal, even mundane stories, than crazy ones – and they were overwhelmingly positive. These experiences have reinforced my faith in what I do. Of course, there are extreme situations, but it is only against the background of everyday life. My true interest in this project is that we can understand the Roma for whom they really are.

Balazs Gardi was born in Budapest, Hungary in 1975. He studied photography and photojournalism and after graduating in 1996, Gardi worked for Népszabadság, the largest Hungarian political daily newspaper. In 2003 he became a freelance photographer and began documenting the everyday life of the Eastern European Roma community. Gardi has received numerous awards for excellence in photojournalism, including being named Photographer of the Year three times in Hungary since 1998; his awards also include those from POYi, World Press and the Photo District News' "30 Under 30" and was a finalist for the W. Eugene Smith Award. In 2002, he spent a term at Cardiff University's School of Journalism, Media and Cultural Studies in Wales, thanks to a Reuters Foundation grant. Gardi is a member of the Association of Hungarian Journalists and the Association of Hungarian Photographic Arts and currently serves as a board member of the Association of Hungarian Press Photographers. Gardi is represented by and can be reached through Getty Images.