|

Seeing Red in Venezuela

February 2007

|

|

||||||||||||

|

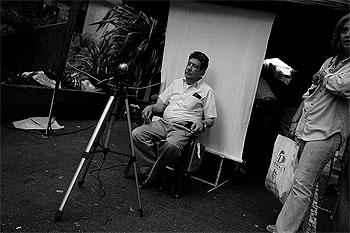

More than any other self-generated story I have done, I approached the Venezuelan presidential election this last December more like a writer than a photographer. Countless articles and reports on the country's political situation fed my interest in Chávez's consolidation of power. I saw very few images from Venezuela before I went and I was driven more by an academic curiosity based on research than a visual curiosity. Approaching the story this way made covering the election and the events surrounding it easier. I arrived with few expectations, no pressure and no editors determining what I should produce visually. Yet, I knew what I was looking for. What I shot was like an affirmation – a kind of visual proof – that satisfied my own curiosity.

Manuel Rosales, the governor of the western, oil-producing Zulia State led the opposition. In the months leading up to the election, he was able to build a cohesive opposition coalition that had been absent from Venezuelan politics for years. Chávez is, in the words of Rosales, "implementing a Castro-style system of autocratic rule in Venezuela."

Leading up to the election, the opposition seemed to gain momentum, thanks in large part to its long list of criticisms concerning Chávez's socialist revolution. The middle class and upper class of Venezuela are in the minority both economically and politically. Among them there is a real sense of alienation from and disenchantment with the country's large public sector. If you are not poor or do not support Chávez, you cannot work in the public sector or benefit from the state's oil-financed social welfare programs. A democratic leader should respect the political minority. In Venezuela, it appears that there is no room for the political minority; it exists but it is not included in the "revolution."

In addition to not doing enough socially with the country’s oil revenues, Chávez is also faulted for his non-democratic leadership. He confiscates farmlands for new government farms. He has halted congressional oversight of the military. Now, the military responds directly to him. Chávez controls almost everything that is in the public sector. He created a new constitution that includes an article allowing the president to be put up for immediate re-election as well as extending the presidential term from 5 to 6 years. Now, there is no longer a bicameral Congress. It was replaced by a unicameral National Assembly. Many believe that with his new victory, Chávez plans to limit private media and eliminate presidential term limits, thus further centralizing the government.

Despite these non-democratic measures, Venezuela is a very forward-moving and paradoxical country. Driving from the airport to Caracas, I could not believe how many billboards for U.S. and multinational companies littered the roadside. Despite all of Chávez's heated rhetoric towards the U.S. and the unbridled capitalism that the U.S. embodies, Venezuela is very tangled up in the same economic system. It seems very difficult, in my eyes, for Chávez to successfully untangle his country from the U.S. and the West and come up the winner in this wrestling match.

Venezuela is an oil-rich OPEC nation but most of its economic might is concentrated in its oil revenues leaving it, as many believe, very vulnerable in the long run and hapless when it comes from cutting its ties with the U.S. Venezuela exports roughly 65 percent of its oil to North America. The U.S. receives one-tenth of its oil imports from Venezuela. American investors are flooding into Venezuela, complicating matters even more. GM and even Halliburton have offices in Venezuela and many American multinationals are becoming very comfortable there. For now, the rhetoric has been enough to keep Chávez in power. However, realistically, his dream might not come to fruition for a long time.

Photographing, or should I say street shooting, in that neighborhood was very difficult for me. It is a Chávez stronghold. I had heard countless horror stories from other shooters of theft, knife attacks, and general harassment and distaste for foreign journalists. It was tough not to shoot; I felt like I missed out on showing the downtown environment in my own way.

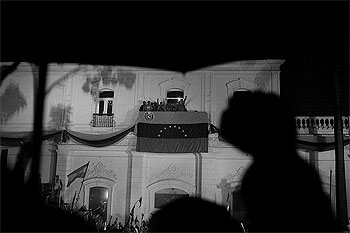

In the Altamira neighborhood of east Caracas, the middle-class and wealthy area of Caracas, you feel like you are in a Los Angeles suburb. At an opposition rally at Plaza Altamira the night after the results were announced, high school, college, and 20-something Rosales supporters gathered with Puma shoes, designer jeans and Abercrombie T-shirts. Many were eager to try out their English on journalists. They dressed like and stood for everything that Chávez felt was wrong with the world - everything that is in the way of his revolution. Here in this welcoming environment, seemingly a world away from downtown, I felt at ease shooting and I was able to take my time and to convey what I wanted.

The Tuesday following the election was my most rewarding day. I had the privilege of visiting the community of Nuevo Amanecer in the Coche barrio of Caracas with four other photographers who had spent a lot of time, some even months, with the community. Nuevo Amanecer is considered a government pioneer community - a community that has risen with the help of a Chávez program that allows people to take over government land that is not being used. With only their hands, this small community had cleared a city waste management junkyard. Yet the area is still filled with garbage, old large garbage trucks and other equipment. The people utilize whatever cleared land exists. They have built their own homes and set up lights that serve as guides at night. Children come home from school and play in and by garbage and rusting equipment. Clothes are dried on ropes connected from one dumpster to the next.

Spending the whole day in this small neighborhood, where I knew that I was welcomed and protected, really freed me in my shooting. I did not have to look over my shoulder and I was able to take my time with the subjects and the environment. All around, it was the most ideal way for me to shoot the barrios, and that was very important to me.

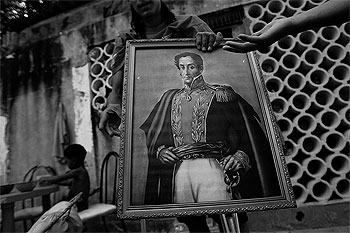

Like many other populists leaders in history, Chávez is in danger of promising socialism while using non-democratic means. He has taken on a romantic role of protecting not only Venezuela but also all of Latin America. Evoking the name and legacy of Simón Bolívar, Chávez has cast himself as the new hero of his country as he pushes forward with the revolution. Bolívar is seen as "the liberator," the man who wrestled Venezuela, Colombia, Peru, Bolivia, and Ecuador from Spain. His actions and writings revealed him to be an adherent of democracy, limited government, separation of powers, freedom of religion, and rule of law. However, Chávez does not seem to be aware of the course his hero took at the end of his political life when he became a broken man as his Gran Colombia experiment began to fall apart in the mid-1820s. Bolívar adopted more centrist means to keep things stable. These methods were seen as antithetical to democratic ideals. After adopting many characteristics of power he stood against, he denounced the project as ungovernable. In 1830, before he could leave for exile, he died from complications of tuberculosis.

© Ramin Rahimian

Dispatches are brought to you by Canon. Send Canon a message of thanks. |

|||||||||||||

Back to February 2007 Contents

|

|